the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Simultaneous measurements of the relative-humidity-dependent aerosol light extinction, scattering, absorption, and single-scattering albedo with a humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer

Jiacheng Zhou

Xuezhe Xu

Qianqian Liu

Yuanqing Cai

Weijun Zhang

Dean S. Venables

Weidong Chen

Hygroscopic aerosols take up water and grow with increasing relative humidity (RH), giving rise to large changes in light extinction (bext), scattering (bscat), absorption (babs), and single scattering albedo (SSA, ω). The optical hygroscopic growth factors for each parameter (f(RH)) are thus important for assessing aerosol effects on regional air quality, atmospheric visibility, and radiative forcing. The RH dependence of aerosol scattering and extinction has been studied in many laboratory and field studies. However, owing partly to the absence of suitable instrumentation, there are few reports of the RH dependence of aerosol absorption and ω. In this work, we report the development of a humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer (H-CEA) for simultaneous measurements of f(RH) at λ=532 nm from 10 % to 88 % RH. The instrument's performance was evaluated with laboratory-generated ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, and nigrosin aerosols. Measured hygroscopic growth factors for different parameters were in good agreement with model calculations and literature-reported values, demonstrating the accuracy of the H-CEA for measuring RH-dependent optical properties.

- Article

(5637 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Atmospheric aerosols directly influence global climate forcing by absorbing and scattering solar radiation (IPCC, 2013; Moise et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2016; Shrivastava et al., 2017). The extinction (sum of absorption and scattering) capacity of aerosol particles strongly influences visibility, especially at high relative humidity (RH) (Massoli et al., 2009a; Liu et al., 2012). Hygroscopic particles can take up water from the surrounding atmosphere, modifying their composition, size, complex refractive index (CRI), and mixing state and thereby altering their optical and radiant properties (Covert et al., 1972; Tang and Munkelwitz, 1994; Zhang et al., 2008; Bian et al., 2009; Kuang et al., 2015). Research on the hygroscopicity of aerosols is therefore crucial for assessing their climate and environmental impacts (Pitchford et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2008; Bian et al., 2009).

Multiple techniques have been developed to characterise aerosol hygroscopic behaviour over the last few decades and have been described in several reviews (Kreidenweis and Asa-Awuku, 2014; Titos et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2019). The instrument commonly used to characterise particle size growth in the laboratory and in field applications is the hygroscopic tandem differential mobility analyser (H-TDMA). The growth factor (GF) is obtained by measuring the ratio of particles under humid and dry conditions (Swietlicki et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2019).

Similarly, the enhancement factor (f(RH)) for optical properties is defined as

where is the extinction, scattering, or absorption coefficient, and ω is the single scattering albedo (SSA, ); and ω are functions of wavelength λ and relative humidity, typically >80 % or 30 %–40 % (Dry). By combining H-TDMA with an optical instrument, size-dependent aerosol optical hygroscopicity can be measured (Michel Flores et al., 2012).

Advances in optical methods have allowed significant progress to be made in studying f(RH). In early work, Baynard et al. (2006) developed a dual-channel cavity ring-down spectrometer (CRDS) for extinction measurements (λ=532 nm) at 80 % RH and under dry conditions (RH<10 %) to measure f(RH)ext. The instrument was used for measuring the RH dependence of the extinction of inorganic aerosols and a mixture of organic and ammonium sulfate aerosols (Baynard et al., 2006; Garland et al., 2007). In 2009, Massoli et al. (2009a) developed a six-channel CRDS for measuring aerosol extinction at λ=355, 532, and 1064 nm at 25 %, 60 %, and 85 % RH. In 2011, an eight-channel CRDS for aircraft observations was developed by Langridge et al. (2011). Three channels (λ=532 nm) were used for RH-dependent extinction measurement at <10 %, 70 %, and 95 % RH. Recently, Zhao et al. (2017) reported the development of a humidified broadband cavity-enhanced aerosol extinction spectrometer (H-BBCES) for measuring the effect of hygroscopicity on extinction at λ=461 nm. These high-finesse cavity-based spectroscopy methods provide valuable, sensitive, and accurate methods for in situ measurement of bext and f(RH)ext (Baynard et al., 2006; Langridge et al., 2011; Michel Flores et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2017).

For measuring f(RH)scat, the humidified nephelometer is widely used (Covert et al., 1972). Commercial nephelometers (Titos et al., 2016) can measure the scattering enhancement factor at a fixed RH or scan over the hygroscopic growth curve between 40 % and 90 % RH (Yan et al., 2009; Fierz-Schmidhauser et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). This approach has been used to investigate how hygroscopic growth affects aerosol scattering properties and to establish the relationship between aerosol chemical composition, diameter hygroscopic growth, and hygroscopicity parameter (Zieger et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015; Kuang et al., 2017). For moderately hygroscopic aerosols, the uncertainty of f(RH)scat was about 20 %–40 % and mainly arose from uncertainties in RH, dry reference state, and nephelometer measurement uncertainties (Titos et al., 2016). The truncation error is unavoidable in current commercial nephelometers (Massoli et al., 2009b), and modifications such as reducing the lamp power or replacing the original RH sensor inside the nephelometer chamber are sometimes needed to improve the accuracy of f(RH)scat measurements (Zhao et al., 2019).

Suitable instruments for measuring f(RH)abs and f(RH)ω are lacking, however. Filter-based instruments such as Aethalometer instruments and particle soot absorption photometers suffer from a change in the nature of the suspended state of the sample and are not suitable for high-RH operation (Arnott et al., 2003). Photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS) is a direct and in situ method for measuring babs (Lack et al., 2006; Moosmüller et al., 2009), but sample RH is commonly controlled in low-RH conditions (10 %–30 % RH), owing to an evaporation-induced bias of about 7 %–30 % (Lack et al., 2009; Langridge et al., 2013). In contrast, recently developed aerosol albedometers allow for simultaneous in situ measurements of bext, bscat, babs, and ω in the same sample volume. These instruments include the cell-reciprocal nephelometer (Mulholland and Choi, 1998; Mulholland and Bryner, 1994; Abu-Rahmah et al., 2006; Mikhailov et al., 2006), the CRDS-reciprocal nephelometer (Strawa et al., 2003), and other optical cavity-based albedometers, including the CRDS albedometer (Thompson et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2012), the BBCES albedometer (Zhao et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018a), and the cavity attenuated phase shift spectroscopy (CAPS) albedometer (Onasch et al., 2015), which combine CRDS/BBCES/CAPS together with integrating spheres (ISs). These albedometers are suitable for operating under high-RH conditions and have sampling advantages over independent measurements of different parameters with different instruments (Wei et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018a).

In this work, we report the first demonstration of a humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer (H-CEA) that combines a BBCES albedometer with a humidigraph system for simultaneous and accurate measurement of f(RH) at λ=532 nm. The instrument performance was tested with laboratory-generated ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, and nigrosine aerosols. The H-CEA provides a new method for direct and in situ measurement of multiple optical hygroscopic parameters with a single instrument.

2.1 Humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer

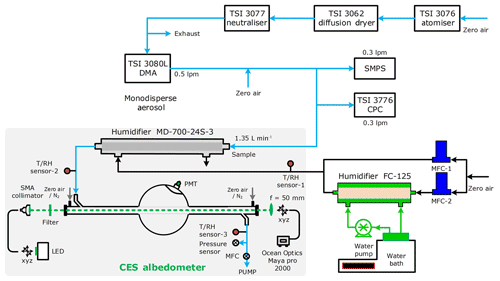

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the H-CEA. The instrument consists of a BBCES albedometer and a RH-controlled system. The albedometer combined the BBCES with an integrating sphere (IS) for simultaneous in situ measurements of bext, bscat, babs, and ω in the same sample volume (Zhao et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018a, b). bext was measured over the range from 518 to 554 nm with a spectral resolution of 0.11 nm. bscat was measured as an integrated scattering coefficient over the spectral region from 528 to 537 nm (centred at 532 nm). Measurement of bext and bscat allows for calculation of babs and ω at a centre wavelength of 532 nm. Truncation reduction tubes narrowed the maximum truncation angle of the integrating sphere to 1.22∘. Truncation losses are negligible for particle diameters below 1 µm. High-reflectivity mirrors (R=99.971 % at λ=532 nm) were mounted at each end of the truncation reduction tubes. The flow rates of the sample (Fs) and purified air near the front mirror (Fi, sample inlet part) and the end mirror (Fo, sample outlet part) were 1.45, 0.05, and 0.1 L min−1, respectively. Some modifications of previous instruments have been made for RH-dependent measurements, including (1) a temperature and RH sensor (T/RH sensor-2) inserted close to the inlet of the cavity cell to accurately measure the RH of the humidified sample and (2) thermal insulation of the optical cavity, sampling tubes, and the Nafion humidifier to reduce the effect of changes in ambient temperature.

Figure 1Schematic diagram of the humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer (H-CEA) and the aerosol-generation system. The H-CEA consists of a controllable gas humidifier system, a Nafion humidifier (MD-700, Perma Pure), and a cavity-enhanced albedometer. The relative humidity (RH) of the aerosol sample was controlled by the Nafion humidifier by adjusting the RH of the sheath gas. The sheath gas RH was controlled by adjusting the flow ratio of a dry gas stream and a wet gas stream by two mass controllers. The wet gas stream was generated using a Nafion humidifier (FC-125, Perma Pure), and a water bath was used to control its temperature. Three temperature and RH sensors were used to monitor the temperature and RH of sheath gas and aerosol samples at inlet and outlet of the cavity cell. The cyan, black, and grey lines represent the aerosol sample, humidified gas, and purging gas flows, respectively.

Data retrieval and calibration of the extinction and scattering measurements have been described elsewhere (Zhao et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018a). The albedometer was periodically flushed with particle-free zero air to obtain the BBCES reference spectrum and reference scattering intensity. High optical stability was achieved by using a high-performance temperature and current controller for the LED light source. No obvious drifts in the transmitted light intensity (fluctuation ∼0.1 %) or PMT (photomultiplier tube) intensity (fluctuation ∼0.5 %) were observed over several hours (Xu et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2017). Detection limits of optical parameters were determined from a Gaussian fit to the frequency distribution of a time series measurement of zero air (Xu et al., 2018a). With a 6 s acquisition time (an average of 150 individual spectra, each with 40 ms exposure time), the 3σ detection limits for bext, bscat, and babs were better than 0.81, 0.25, and 0.77 Mm−1, respectively. The accuracy of the albedometer was evaluated with laboratory-generated polystyrene latex (PSL) spheres and ammonium sulfate aerosols. The total uncertainties in bext, bscat, babs, and ω measurements were estimated to be 3.8 %, 3.5 %, 5.2 %, and 3.3 %, respectively. Uncertainties in bext mainly arose from the calibrations of the mirror reflectivity (1−R, ∼2.5 %) and effective sample length (RL, ∼0.6 %), as well as from particle losses. Uncertainty contributions associated with the scattering measurement include the scattering factor determination (<2 %), scattering truncation losses (<1 %, for submicron particles), and particle losses. Since measurements of bext and bscat were over mostly the same sample volume, the effect of particle losses on to ω measurement was considered negligible.

2.2 Humidigraph system

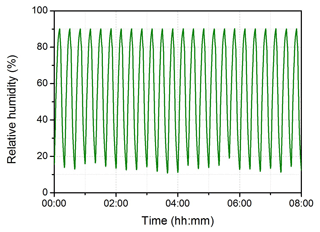

The humidigraph system (as shown in Fig. 1) consists of a gas humidity-adjusting system that generates humid gas and a second Nafion humidifier (MD-700-24S-3, Perma Pure) to humidify the aerosol sample. Dry zero air was divided into two paths separately controlled by two mass flow controllers (MFCs): one was humidified with a Nafion humidifier (FC-125, Perma Pure, the water was supported by an automatic temperature-controlled water bath) and the other was used as dry bypass air to adjust the RH of the air. A program controlled the mixing ratios of the humid air and bypass air, allowing the RH of the zero air to be varied from 2 % to 98 % RH (monitored with T/RH sensor-1, Rotronic HC2-C05, with accuracies of ±0.2 ∘C and ±1.5 % RH at 23 ∘C). The zero air was then used as the sheath air to humidify the sampling aerosol flow. The achievable RH of the aerosol sample ranged from 10 % to 90 % (as shown in Fig. 2) and was monitored with the T/RH sensor-2. A cycle from 10 % to 90 % RH and back again with the humidigraph system took 15–20 min depending on experimental conditions.

2.3 Laboratory test and model evaluation f(RH) measurement

The performance evaluation of H-CEA was carried out using laboratory-generated monodispersed particles of ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, and nigrosin. The aerosol-generation system is shown in Fig. 1. Polydisperse aerosol particles were generated with a constant output atomiser (TSI 3076), dried in a diffusion dryer (TSI 3062), and then charged with an aerosol neutraliser (TSI 3077) (Zhao et al., 2013, 2014). A quasi-monodisperse size distribution of particles was selected using a differential mobility analyser (DMA, TSI 3080L), diluted in dry zero air, and transferred to the H-CEA and a condensation particle counter (CPC, TSI 3776) for measuring optical properties and particle number concentration, respectively. A scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS) in front of the H-CEA measured the size distribution of size-selected particles.

The extinction, scattering, and absorption coefficients of size-selected particles can be calculated using the following equation (Pettersson et al., 2004):

where N(Dp) is the number concentration of particles in size bin dDp with mean diameter Dp; is the CRI of the particles, where n and k are the real and imaginary parts of the CRI, respectively. is the size parameter. represents the extinction, scattering or absorption cross sections () for a particle of given size and can be obtained with the measured and N(Dp) . For chemically homogeneous spherical particles, σext,scat can be calculated using Mie theory.

The model calculation of f(RH)ext,scat was similar to the method described in Zhao et al. (2017). The method was as follows: (a) the measured size distribution of size-selected particles was used to calculate a normalised size distribution; (b) the hygroscopic growth factors for a particular diameter Dp (GF(RH, Dp)) were calculated with the Extended Aerosol Inorganics Model (E-AIM) (Wexler and Clegg, 2002); (c) the CRIs of wet particles (mwet) were obtained using the volume-weighted mixing rule with CRI values of water and sample aerosol particles (Michel Flores et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2017); (d) the normalised extinction and scattering cross sections ( of dry and wet particles were calculated using Mie theory with CRI values of dry and wet particles; and finally (e), the f(RH)ext,scat were calculated from the ratio of the wet and dry values of σext,scat . In this work, pure scattering ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride were used for evaluating the measurement of f(RH)ext,scat, and strongly absorbing nigrosin particles were used to test the measurement of f(RH)abs,ω. Because the literature data reported for G(RH) are limited, the model only calculated f(RH)ext,scat for ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride aerosols, not for nigrosin aerosols. CRIs used were 1.335+i0 (Daimon and Masumura, 2007), 1.504+i0 (Michel Flores et al., 2012), and 1.551+i0 (Querry, 1987) for water, ammonium sulfate, and sodium chloride at λ=532 nm, respectively.

3.1 Characterisation of the H-CEA

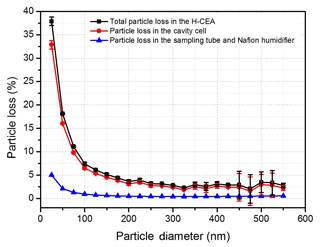

3.1.1 Particle wall loss

Particle losses in the H-CEA were evaluated using laboratory-generated ammonium sulfate particles by measuring the number concentrations of size-selected particles (as shown in Fig. 3). The particle loss was characterised based on the difference in concurrent CPC measurements at the inlet and outlet of the sample tube or cavity, after accounting for dilution inside the cavity. Losses considered included particle loss in the tube, in the Nafion humidifier, and in the cavity cell. For particle diameters above 40 nm, the literature-reported losses in the Nafion humidifier were estimated to be less than 1 % (Bohensky et al., 2014). For particles larger than 100 nm, the measured total particle loss in the H-CEA was less than 7 %, with a <1 % loss in the sample tube and Nafion humidifier, and <6 % loss in the cavity cell. The larger particle losses for small particles were mainly caused by the Brownian diffusion to the walls of the tube and cavity cell (von der Weiden et al., 2009). For ambient measurements, particle losses contributed less than 3 % uncertainty to the extinction and scattering measurements.

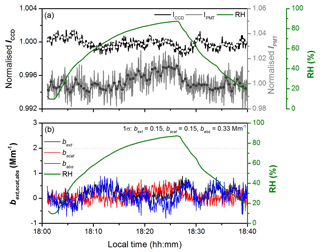

3.1.2 Effect of water vapour on optical signal

To confirm that the influence of water vapour on the measurements of bext, bscat, and babs was negligible, the relative changes in light intensity (ICCD), scattering intensity (IPMT), and for humidified air were measured during a full RH cycle. As shown in Fig. 4a, ICCD did not show obvious changes with RH. IPMT increased slightly at high RH, but the overall increment in IPMT was less than 2.5 % for RH ranging from 10 % to 88 %. The calculated values of bext, bscat, and babs did not show obvious changes with RH (Fig. 4b). The respective standard deviations were 0.15, 0.15, and 0.33 Mm−1 and were within the precision of the albedometer. These results demonstrated that water vapour content had no statistically significant effect on the measurement of bext, bscat, or babs.

3.1.3 Uncertainty analysis for f(RH) measurements

A power-law dependence of bext and bscat on RH is commonly used to describe hygroscopic behaviour (f(RH)) (Quinn et al., 2005; Massoli et al., 2009a). Using this parameterisation, Titos et al. (2016) comprehensively analysed the uncertainty in f(RH)scat measurements with Monte Carlo simulations (Saltelli et al., 2000). We used a similar method in our study to evaluate the uncertainty in f(RH)ext,scat measurements with H-CEA. The uncertainty in f(RH) mainly arose from the uncertainties in the extinction and scattering measurements and the measurement of RH. The relative uncertainties of these properties are denoted δf(RH), δbext,scat, and δRH. These properties can be described with the following expressions:

In the simulation, δbext and δbscat were the relative uncertainties of bext and bscat with values of 3.8 % and 3.5 %, respectively. bext and bscat were randomly selected from 10 to 1000 Mm−1 by taking into account upper and lower limits of the uncertainties (ranging from 1 to ). Values of bext,scat of the aerosol sample in wet and dry conditions (Dry = 20 % RH) were calculated with the power-law functions (Eqs. 5 and 6). The relative uncertainty of RH measurement (δRH ∼1.5 %) contributed to the total uncertainties of bext,scat, which will be enlarged with the increment of γext and γscat.

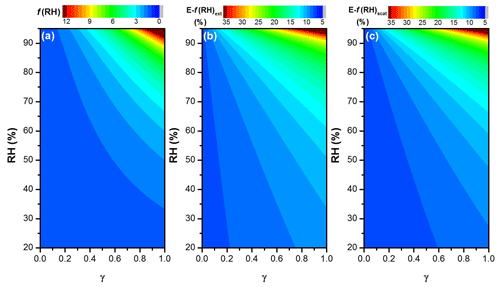

Figure 5Simulated dependence of (a) f(RH)ext,scat, (b) error of f(RH)ext, and (c) error of f(RH)scat on the hygroscopic parameter γ and RH. The reference RH value was 20 % RH in these simulations.

Figure 5 shows the results of the simulated f(RH)ext,scat and uncertainties of f(RH)ext and f(RH)scat as a function of hygroscopic parameter γ and RH with a reference RH of 20 %. In the simulation, RH was varied from 20 % to 95 % with a step of 1 %, and the hygroscopic parameter γ was varied from 0 to 1 with a step of 0.01. The average errors of f(RH)ext and f(RH)scat were estimated to be 11 % and 10 % for RH in the range from 20 % to 95 %. For moderately hygroscopic aerosols (γ∼0.5), the uncertainties of f(RH)ext and f(RH)scat ranged from 7 % to 25 %. The uncertainties reported for our H-CEA instrument were about half those of the humidified nephelometer (20 %–40 % for f(RH)scat) reported by Titos et al. (2016). A power-law dependence of babs on RH has not been reported in previous studies and is not expected. That is because condensation of water or other non-absorbing species onto a particle does not increase the total amount of absorbing molecules on that particle, unlike the contribution of condensing species to particle scattering. For this reason, the Monte Carlo simulation was not used to model the uncertainty in f(RH)abs. If any power-law relationship exists, the expected values of γabs and γω were much smaller than γext,scat and the uncertainty of f(RH)abs and f(RH)ω should be less than f(RH)ext and f(RH)scat.

3.2 Laboratory results

A series of laboratory experiments were conducted to evaluate the performance of the H-CEA. For measurement of f(RH)ext,scat, size-selected non-absorbing inorganic particles (ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride) were used. The results were compared with the model calculations and values reported in the literature. Measurement of f(RH)abs,ω was assessed using size-selected strongly absorbing organic particles (nigrosin). Results were compared to previous findings in the literature.

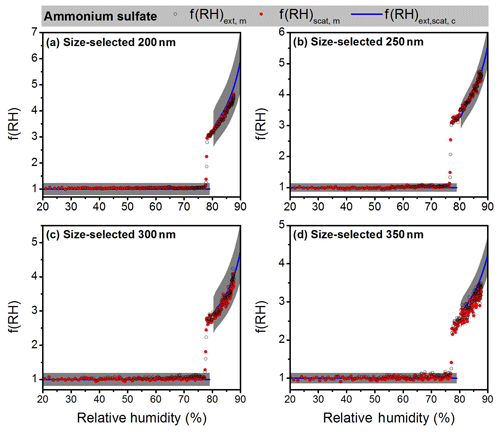

Figure 6RH dependence of extinction and scattering enhancement for size-selected (a) 200 nm, (b) 250 nm, (c) 300 nm, and (d) 350 nm dry diameter ammonium sulfate particles. The black circles and red dots represent the measured extinction (f(RH)ext,m) and scattering (f(RH)scat,m) hygroscopic enhancement, respectively. The blue lines represent the model calculations with Mie theory, and the grey areas represent the uncertainty bounds estimated from the measured size distribution of size-selected particles from the SMPS.

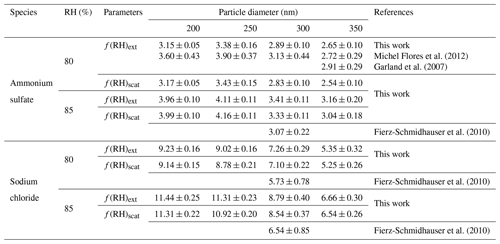

Table 1Comparison of the measured RH-dependent extinction and scattering coefficients for the size-selected ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride particles.

Table 2Comparison between the measured and E-AIM-calculated extinction and scattering cross sections for the size-selected ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride particles under three selected RH conditions.

3.2.1 Ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride

Figure 6 shows the RH-dependent extinction and scattering for the size-selected ammonium sulfate particles of 200, 250, 300, and 350 nm (dry diameters, with RH of ∼20 %, the same as below for sodium chloride and nigrosin). The black circles and red dots represent the measured extinction and scattering hygroscopic enhancement (f(RH)). The blue lines represent the model calculation results with Mie theory using the theoretical GF(RH) from E-AIM (Fierz-Schemidhauser et al., 2010; Michel Flores et al., 2012). There were no significant differences in the values of f(RH)scat and f(RH)ext for particles of four different diameters, and their values in the range of ∼10 % to 77 % RH were close to 1, consistent with model calculations. The sudden increase in f(RH)ext,scat was due to the deliquescence of ammonium sulfate particles. The measured deliquescence RH (DRH) of ammonium sulfate was 77 %–78 %, close to the literature reported value (79.9 % RH at 298 K) (Tang and Munkelwitz, 1993). The small difference may arise from slight temperature and RH differences at different parts of the system as well as the accuracy of the T/RH sensor (±1.5 %). Table 1 gives f(RH)ext (and f(RH)scat) for size-selected particles of 200, 250, 300, and 350 nm particles measured at 80 % RH. Also included are the results reported by Michel Flores et al. (2012), using a combined system of humidified CRDS and H-TDMA, and by Garland et al. (2007), using a humidified CRDS instrument. Our values were in good agreement with both studies. At RH = 85 %, our f(RH)scat value for 300 nm particles of 3.33±0.11 was consistent with the value (3.07±0.22) measured with a humidified nephelometer instrument (Fierz-Schemidhauser et al., 2010). Overall, the f(RH)ext,scat measurements for sulfate particles were in good agreement with the model calculations and literature-reported values (see Table 1). The measured extinction and scattering cross sections agreed with values calculated using E-AIM for different particle diameters and RH conditions (Table 2). The overall consistency between H-CEA measurements and other measured and calculated values in the literature indicates the reliability of the H-CEA instrument.

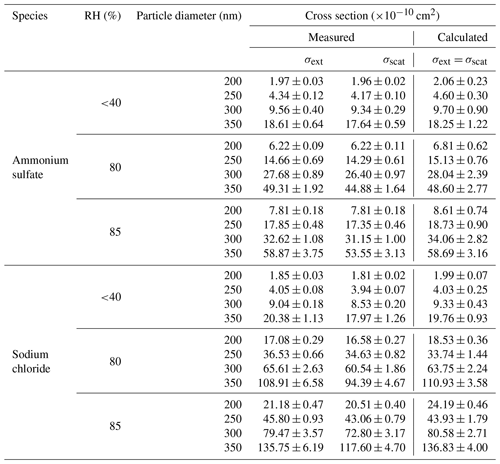

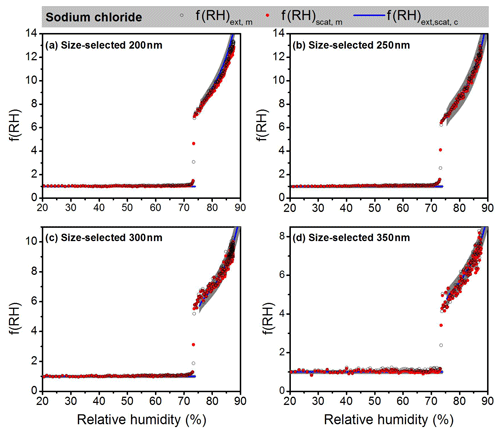

Figure 7RH dependence of extinction and scattering enhancement for size-selected (a) 200 nm, (b) 250 nm, (c) 300 nm, and (d) 350 nm dry diameter sodium chloride particles. The black circles and red dots represent the measured extinction (f(RH)ext,m) and scattering (f(RH)scat,m) hygroscopic enhancement, respectively. The blue lines represent the model calculations with Mie theory, and the grey areas represent the uncertainty bounds estimated from the measured size distribution of size-selected particles with SMPS.

Figure 7 shows the f(RH)ext,scat values for size-selected 200, 250, 300, and 350 nm sodium chloride particles. The measured DRH of sodium chloride was ∼73 %, which was close to the value reported in the literature (75.3 % RH at 298 K) (Tang and Munkelwitz, 1993). Table 1 lists the measured f(RH)ext∕scat at 80 % and 85 % RH. The f(RH)scat values for 300 nm particles were larger than the values reported by Fierz-Schemidhauser et al. (2010) using a humidified nephelometer instrument. This difference likely arises from the accuracy of our RH measurement of our sample. Our deliquescence points are about 2 % lower RH than literature values, suggesting that the actual RH in our system was marginally higher than 80 % or 85 %. As f(RH)ext∕scat shows a strong positive dependence on RH, the actual values are likely to be lower in our instrument. This effect is most marked for sodium chloride particles, where the enhancement factor (0.3 at 85 % RH, 300 nm particles) is about double that of the ammonium sulfate particles (0.1 at 85 % RH, 300 nm particles). In addition, differences in the particle size distribution between our study and that of Fierz-Schemidhauser et al. (2010) may also contribute to the observed difference in f(RH)scat. The f(RH)ext,scat values of sodium chloride particles were in good agreement with the model calculations, which were obviously larger than those of ammonium sulfate.

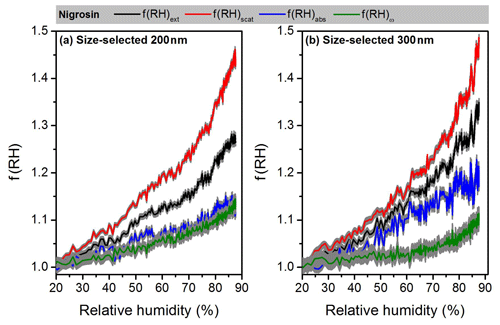

3.2.2 Nigrosin

The performance evaluation of the H-CEA for f(RH)abs and f(RH)ω measurements was demonstrated with laboratory-generated nigrosin aerosol, which absorbs strongly at 532 nm (Xu et al., 2018a). Figure 8 shows the measured f(RH) for size-selected 200 and 300 nm nigrosin particles. For 200 nm nigrosin particles, the measured f(RH)ext, f(RH)scat, f(RH)abs, and f(RH)ω at 80 % RH were 1.22±0.00, 1.34±0.00, 1.12±0.01, and 1.10±0.00, respectively. These values were 1.26±0.01, 1.34±0.02, 1.18±0.01, and 1.06±0.01, respectively, for 300 nm nigrosin particles. The measured f(RH)scat of nigrosin particles at 200 and 300 nm were roughly the same; however, the measured f(RH) values were slightly different for these two particle sizes, which showed a hygroscopic increase in absorption. In this study, the measured f(RH)ext values at 80 % RH were comparable with the results of Michel Flores et al. (2012) (1.18±0.06 for 200 nm particles, and 1.19±0.04 for 300 nm particles) using a humidified CRDS instrument. The measured f(RH)abs value in this study was also consistent with the value (∼1.14) reported by Brem et al. (2012). f(RH)ω shown a monotonic increase with RH, which may be due to a decrease in the imaginary part of CRI.

Figure 8RH dependence of extinction, scattering, absorption, and ω enhancement for size-selected (a) 200 nm and (b) 300 nm dry diameter nigrosin particles. The black, red, blue, and green lines represent the measured f(RH)ext, f(RH)scat, f(RH)abs, and f(RH)ω, respectively. The grey areas represent the measurement uncertainties.

In this paper, we report the development and characterisation of a humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer (H-CEA) for the simultaneous measurements of multiple optical hygroscopic parameters (f(RH)) of the same sample. Monte Carlo simulations were used to evaluate the uncertainties in f(RH)ext,scat measurements. For moderately hygroscopic aerosols, the estimated uncertainties for f(RH)ext,scat were lower than 25 % over the RH range from 20 % to 95 %. The uncertainties reported here were about half those of an earlier humidified nephelometer. Laboratory-generated size-selected ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, and nigrosin aerosols were used to evaluate the instrument's performance. The measured f(RH)ext,scat showed good agreement with model calculations and literature-reported results, demonstrating the accuracy of the f(RH)ext,scat measurements. The f(RH)abs values of nigrosin aerosol reported here were consistent with previous literature-reported results, and the RH-dependent f(RH)ω was reported for the first time. Laboratory measurements demonstrated that the H-CEA provides a valuable method for aerosol hygroscopic property research, especially for light-absorbing aerosols.

The data used in this study can be obtained from https://pan.baidu.com/s/1hlFEJQPwKX8gJH9ZRs0KMw (Zhou et al., 2020). The extraction code is m7ub (last access: 22 April 2020).

XX and WZ designed the research. JZ, XX, WZ, and BF built the device. JZ, QL, and YC conducted the experiment. JZ and XX analysed data. JZ performed the simulation. JZ, XX, WZ, and DSV wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 4190050321), the Instrument Developing Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. YJKYYQ20180049), the CASHIPS Director's Fund (grant no. BJPY2019B02, YZJJ2019QN3), the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (grant no. 1908085QD157), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (grant no. 2016383).

This paper was edited by Mingjin Tang and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abu-Rahmah, A., Arnott, W. P., and Moosmüller, H.: Integrating nephelometer with a low truncation angle and an extended calibration scheme, Meas. Sci. Technol., 17, 1723–1732, https://https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-0233/17/7/010, 2006.

Arnott, W. P., Moosmüller, H., Sheridan, P. J., Ogren, J. A., Raspet, R., Slaton, W. V., Hand, J. L., Kreidenweis, S. M., and Collett Jr., J. L.: Photoacoustic and filter-based ambient aerosol light absorption measurements: Instrument comparisons and the role of relative humidity, J. Geophys. Res., 108, 4034, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002165, 2003.

Baynard, T., Garland, R. M., Ravishankara, A. R., Tolbert, M. A., and Lovejoy, E. R.: Key factors influencing the relative humidity dependence of aerosol light scattering, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L06813, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL024898, 2006.

Bian, H., Chin, M., Rodriguez, J. M., Yu, H., Penner, J. E., and Strahan, S.: Sensitivity of aerosol optical thickness and aerosol direct radiative effect to relative humidity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2375–2386, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2375-2009, 2009.

Bohensky, G., Sunada, C., Smith, P., Wiedensohler, A., and Tuch, T.: Characterizing the Particle Losses of a Large Diameter Nafion® Dryer, available at: https://www.permapure.com/scientific-emissions/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/MD-700-TROPOS-Presentation-10-2014.pdf (last access: 20 May 2020), 2014.

Brem, B. T., Mena Gonzalez, F. C., Meyers, S. R., Bond, T. C., and Rood, M. J.: Laboratory-Measured Optical Properties of Inorganic and Organic Aerosols at Relative Humidities up to 95 %, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 46, 178–190, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2011.617794, 2012.

Cheng, Y., Wiedensohler, A., Eichler, H., Heintzenberg, J., Tesche, M., Ansmann, A., Wendisch, M., Su, H., Althausen, D., and Herrmann, H.: Relative humidity dependence of aerosol optical properties and direct radiative forcing in the surface boundary layer at Xinken in Pearl River Delta of China: An observation based numerical study, Atmos. Environ., 42, 6373–6397, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.04.009, 2008.

Chen, J., Zhao, C. S., Ma, N., and Yan, P.: Aerosol hygroscopicity parameter derived from the light scattering enhancement factor measurements in the North China Plain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 8105–8118, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-8105-2014, 2014.

Covert, D. S., Charlson, R. J., and Ahlquist, N. C.: A study of the relationship of chemical composition and humidity to light scattering by aerosols, J. Appl. Meteorol., 11, 968–976, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1972)011<0968:ASOTRO>2.0.CO;2, 1972.

Daimon, M. and Masumura, A.: Measurement of the refractive index of distilled water from the near-infrared region to the ultraviolet region, Appl. Opt., 46, 3811–3820, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.46.003811, 2007.

Fang, B., Zhao, W., Xu, X., Zhou, J., Ma, X., Wang, S., Zhang, W., Venables, D. S., and Chen, W.: Portable broadband cavity-enhanced spectrometer utilizing Kalman filtering: application to real-time, in situ monitoring of glyoxal and nitrogen dioxide, Opt. Exp., 25, 26910–26922, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.026910, 2017.

Fierz-Schmidhauser, R., Zieger, P., Wehrle, G., Jefferson, A., Ogren, J. A., Baltensperger, U., and Weingartner, E.: Measurement of relative humidity dependent light scattering of aerosols, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 3, 39–50, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-3-39-2010, 2010.

Garland, R. M., Ravishankara, A. R., Lovejoy, E. R., Tolbert, M. A., and Baynard, T.: Parameterization for the relative humidity dependence of light extinction: Organic-ammonium sulfate aerosol, J. Geophys. Res., 112, D19303, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008179, 2007.

IPCC: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA, 2013.

Kreidenweis, S. M. and Asa-Awuku, A.: 5.13 – Aerosol Hygroscopicity: Particle Water Content and Its Role in Atmospheric Processes, in: Treatise on Geochemistry, 2nd Edn., edited by: Turekian, H. D. H. K., Elsevier, Oxford, 331–361, 2014.

Kuang, Y., Zhao, C. S., Tao, J. C., and Ma, N.: Diurnal variations of aerosol optical properties in the North China Plain and their influences on the estimates of direct aerosol radiative effect, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5761–5772, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5761-2015, 2015.

Kuang, Y., Zhao, C., Tao, J., Bian, Y., Ma, N., and Zhao, G.: A novel method for deriving the aerosol hygroscopicity parameter based only on measurements from a humidified nephelometer system, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 6651–6662, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-6651-2017, 2017.

Lack, D. A., Lovejoy, E. R., Baynard, T., Pettersson, A., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Aerosol absorption measurement using photoacoustic spectroscopy: Sensitivity, calibration, and uncertainty developments, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 40, 697–708, https://https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820600803917, 2006.

Lack, D. A., Quinn, P. K., Massoli, P., Bates, T. S., Coffman, D., Covert, D. S., Sierau, B., Tucker, S., Baynard, T., Lovejoy, E., Murphy, D. M., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Relative humidity dependence of light absorption by mineral dust after long-range atmospheric transport from the Sahara, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L24805, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041002, 2009.

Langridge, J. M., Richardson, M. S., Lack, D., Law, D., and Murphy, D. M.: Aircraft instrument for comprehensive characterization of aerosol optical properties, part I: wavelength-dependent optical extinction and its relative humidity dependence measured using cavity ringdown spectroscopy, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 45, 1305–1318, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2011.592745, 2011.

Langridge, J. M., Richardson, M. S., Lack, D. L., Brock, C. A., and Murphy, D. M.: Limitations of the photoacoustic technique for aerosol absorption measurement at high relative humidity, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 47, 1163–1173, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2013.827324, 2013.

Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Cheng, Y., Hu, M., and Han, T.: Aerosol hygroscopicity and its impact on atmospheric visibility and radiative forcing in Guangzhou during the 2006 PRIDE-PRD campaign, Atmos. Environ., 60, 59–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.06.016, 2012.

Ma, L. and Thompson, J. E.: Optical properties of dispersed aerosols in the near ultraviolet (355 nm): measurement approach and initial data, Anal. Chem., 84, 5611–5617, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac3005814, 2012.

Massoli, P., Bates, T. S., Quinn, P. K., Lack, D. A., Baynard, T., Lerner, B. M., Tucker, S. C., Brioude, J., Stohl, A., and Williams, E. J.: Aerosol optical and hygroscopic properties during TexAQS-GoMACCS 2006 and their impact on aerosol direct radiative forcing, J. Geophys. Res., 114, D00F07, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD011604, 2009a.

Massoli, P., Murphy, D. M., Lack, D. A., Baynard, T., Brock, C. A., and Lovejoy, E. R.: Uncertainty in light scattering measurements by TSI Nephelometer: Results from laboratory studies and implications for ambient measurements, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 42, 1064–1074, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820903156542, 2009b.

Michel Flores, J., Bar-Or, R. Z., Bluvshtein, N., Abo-Riziq, A., Kostinski, A., Borrmann, S., Koren, I., Koren, I., and Rudich, Y.: Absorbing aerosols at high relative humidity: linking hygroscopic growth to optical properties, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 5511–5521, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-5511-2012, 2012.

Mikhailov, E., Vlasenko, S., Podgorny, I., Ramanathan, V., and Corrigan, C.: Optical properties of soot-water drop agglomerates: An experimental study, J. Geophys. Res., 111, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006389, 2006.

Moise, T., Flores, J. M., and Rudich, Y.: Optical properties of secondary organic aerosols and their changes by chemical processes, Chem. Rev., 115, 4400–4439, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr5005259, 2015.

Moosmüller, H., Chakrabarty, R. K., and Arnott,W. P.: Aerosol light absorption and its measurement: a review, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 110, 844–878, https://https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2009.02.035, 2009.

Mulholland, G. W. and Bryner, N. P.: Radiometric model of the transmission cell-resiprocal nephelometer, Atmos. Environ., 28, 873–887, https://doi.org/10.1016/1352-2310(94)90246-1, 1994.

Mulholland, G. W. and Choi, M. Y.: Measurement of the mass specific extinction coefficient for acetylene and ethene smoke using the Large Agglomerate Optics Facility, Proceedings of the 27th Symposium (International) on Combustion, 27, 1515–1522, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(98)80559-6, 1998.

Onasch, T. B., Massoli, P., Kebabian, P. L., Hills, F. B., Bacon, F. W., and Freedman, A.: Single scattering albedo monitor for airborne particulates, Aerosol. Sci. Technol., 49, 267–279, https://https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2015.1022248, 2015.

Pettersson, A., Lovejoy, E. R., Brock, C. A., Brown, S. S., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Measurement of aerosol optical extinction at 532 nm with pulsed cavity ring down spectroscopy, J. Aerosol Sci., 35, 995–1011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2004.02.008, 2004.

Pitchford, M., Malm, W., Schichtel, B., Kumar, N., Lowenthal, D., and Hand, J.: Revised algorithm for estimating light extinction from IMPROVE particle speciation data, J. Air Waste Manage., 57, 1326–1336, https://doi.org/10.3155/1047-3289.57.11.1326, 2007.

Querry, M. R.: Optical constants of minerals and other materials from the millimeter to the ultraviolet, CRDEC-CR-88009, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Aberdeen, MD, USA, 1987.

Quinn, P. K., Bates, T. S., Baynard, T., Clarke, A. D., Onasch, T. B., Wang, W., Rood, M. J., Andrews, E., Allan, J., Carrico, C. M., Coffman, D., and Worsnop, D.: Impact of particulate organic matter on the relative humidity dependence of light scattering: A simplified parameterization, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L22809, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL024322, 2005.

Saltelli, A., Chan, K., and Scott, E. M.: Sensitivity Analysis: Probability and Statistics Series, New York: Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, 2000.

Shrivastava, M., Cappa, C. D., Fan, J., Goldstein, A. H., Guenther, A. B., Jimenez, J. L., Kuang, C., Laskin, A., Martin, S. T., Ng, N. L., Petaja, T., Pierce, J. R., Rasch, P. J., Roldin, P., Seinfeld, J. H., Shilling, J., Smith, J. N., Thornton, J. A., Volkamer, R., Wang, J., Worsnop, D. R., Zaveri, R. A., Zelenyuk, A., and Zhang, Q.: Recent advances in understanding secondary organic aerosol: Implications for global climate forcing, Rev. Geophys., 55, 509–559, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016RG000540, 2017.

Strawa, A. W., Castaneda, R., Owano, T., Baer, D. S., and Paldus, B. A.: The measurement of aerosol optical properties using continuous wave cavity ring-down techniques, J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol., 20, 454–465, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0426(2003)20<454:TMOAOP>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Swietlicki, E., Hansson, H.-C., Hämeri, K., Svenningsson, B., Massling, A., Mcfiggans, G., Mcmurry, P. H., Petäjä, T., Tunved, P., Gysel, M., Topping, D., Weingartner, E., Baltensperger, U., Rissler, J., Wiedensohler, A., and Kulmala, M.: Hygroscopic properties of submicrometer atmospheric aerosol particles measured with H-TDMA instruments in various environments – a review, Tellus B, 60, 432–469, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2008.00350.x, 2008.

Tang, I. N. and Munkelwitz, H. R.: Composition and temperature-dependence of the deliquescence properties of hygroscopic aerosols, Atmos. Environ., 27, 467–473, https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-1686(93)90204-C, 1993.

Tang, I. N. and Munkelwitz, H. R.: Water activities, densities, and refractive indices of aqueous sulfates and sodium nitrate droplets of atmospheric importance, J. Geophys. Res., 99, 18801–18808, https://doi.org/10.1029/94JD01345, 1994.

Tang, M. J., Cziczo, D. J., and Grassian, V. H.: Interactions of water with mineral dust aerosol: water adsorption, hygroscopicity, cloud condensation and ice nucleation, Chem. Rev., 116, 4205–4259, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00529, 2016.

Tang, M., Chan, C. K., Li, Y. J., Su, H., Ma, Q., Wu, Z., Zhang, G., Wang, Z., Ge, M., Hu, M., He, H., and Wang, X.: A review of experimental techniques for aerosol hygroscopicity studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 12631–12686, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-12631-2019, 2019.

Titos, G., Cazorla, A., Zieger, P., Andrews, E., Lyamani, H., Granados-Muñoz, M. J., Olmo, F. J., and Alados-Arboledas, L.: Effect of hygroscopic growth on the aerosol light-scattering coefficient: A review of measurements, techniques and error sources, Atmos. Environ., 141, 494–507, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.07.021, 2016.

Thompson, J. E., Barta, N., Policarpio, D., and DuVall, R.: A fixed frequency aerosol albedometer, Opt. Express, 16, 2191–2205, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.002191, 2008.

von der Weiden, S.-L., Drewnick, F., and Borrmann, S.: Particle Loss Calculator – a new software tool for the assessment of the performance of aerosol inlet systems, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 2, 479–494, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2-479-2009, 2009.

Wei, Y., Ma, L., Cao, T., Zhang, Q., Wu, J., Buseck, P. R., and Thompson, J. E.: Light scattering and extinction measurements combined with laser-induced incandescence for the real-time determination of soot mass absorption cross section, Anal. Chem., 85, 9181–9188, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac401901b, 2013.

Wexler, A. S. and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric aerosol models for systems including the ions H+, NH, Na+, SO, NO, Cl−, Br−, and H2O, J. Geophys. Res., 107, 4207, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000451, 2002.

Xu, X., Zhao, W., Zhang, Q., Wang, S., Fang, B., Chen, W., Venables, D. S., Wang, X., Pu, W., Wang, X., Gao, X., and Zhang, W.: Optical properties of atmospheric fine particles near Beijing during the HOPE-J3A campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 6421–6439, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-6421-2016, 2016.

Xu, X., Zhao, W., Fang, B., Zhou, J., Wang, S., Zhang, W., Venables, D. S., and Chen, W.: Three-wavelength cavity-enhanced albedometer for measuring wavelength-dependent optical properties and single-scattering albedo of aerosols, Opt. Express, 26, 33484–33500, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.033484, 2018a.

Xu, X., Zhao, W., Qian, X., Wang, S., Fang, B., Zhang, Q., Zhang, W., Venables, D. S., Chen, W., Huang, Y., Deng, X., Wu, B., Lin, X., Zhao, S., and Tong, Y.: The influence of photochemical aging on light absorption of atmospheric black carbon and aerosol single-scattering albedo, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 16829–16844, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-16829-2018, 2018b.

Yan, P., Pan, X., Tang, J., Zhou, X., Zhang, R., and Zeng, L.: Hygroscopic growth of aerosol scattering coefficient: A comparative analysis between urban and suburban sites at winter in Beijing, Particuology, 7, 52–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2008.11.009, 2009.

Zhang, L., Sun, J. Y., Shen, X. J., Zhang, Y. M., Che, H., Ma, Q. L., Zhang, Y. W., Zhang, X. Y., and Ogren, J. A.: Observations of relative humidity effects on aerosol light scattering in the Yangtze River Delta of China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 8439–8454, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-8439-2015, 2015.

Zhang, R., Khalizov, A. F., Pagels, J., Zhang, D., Xue, H., and McMurry, P. H.: Variability in morphology, hygroscopicity, and optical properties of soot aerosols during atmospheric processing, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 10291–10296, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0804860105, 2008.

Zhao, C. S., Yu, Y. L., Kuang Y., Tao, J. C., and Zhao, G.: Recent progress of aerosol light-scattering enhancement factor studies in China, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 36, 1015–1026, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-019-8248-1, 2019.

Zhao, W., Dong, M., Chen, W., Gu, X., Hu, C., Gao, X., Huang, W., and Zhang, W.: Wavelength resolved optical extinction measurements of aerosols using broad-band cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy over the spectral range of 445–480 nm, Anal. Chem., 85, 2260–2268, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac303174n, 2013.

Zhao, W., Xu, X., Dong, M., Chen, W., Gu, X., Hu, C., Huang, Y., Gao, X., Huang, W., and Zhang, W.: Development of a cavity-enhanced aerosol albedometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 2551–2566, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-2551-2014, 2014.

Zhao, W., Xu X., Fang, B., Zhang, Q., Qian, X., Wang, S., Liu, P., Zhang, W., Wang, Z., Liu, D., Huang, Y., Venables, D. S., and Chen, W.: Development of an incoherent broad-band cavity-enhanced aerosol extinction spectrometer and its application to measurement of aerosol optical hygroscopicity, Appl. Opt., 56, E16–E22, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.56.000E16, 2017.

Zhou, J., Xu, X., Zhao, W., and Zhang, W.: Simultaneous measurements of the relative-humidity-dependent aerosol light extinction, scattering, absorption, and single-scattering albedo with a humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer (Version Published data), available at: https://pan.baidu.com/s/1hlFEJQPwKX8gJH9ZRs0KMw, 2020.

Zieger, P., Fierz-Schmidhauser, R., Gysel, M., Ström, J., Henne, S., Yttri, K. E., Baltensperger, U., and Weingartner, E.: Effects of relative humidity on aerosol light scattering in the Arctic, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 3875–3890, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-3875-2010, 2010.