the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Peering into the heart of thunderstorm clouds: insights from cloud radar and spectral polarimetry

Christine Unal

Lightning is a natural phenomenon that can be dangerous to humans. It is therefore challenging to study thunderstorm clouds using direct observations since it can be dangerous to fly into them. In this study, a cloud radar at 35 GHz with 45° elevation is used to study the properties and dynamics of thunderstorm clouds. It is based on a thunderstorm case on 18 June 2021 from 16:10 to 17:45 UTC near Cabauw, the Netherlands. The observed thunderstorm was associated with severe weather conditions over The Netherlands, attributed to the remnants of storm “Bill”. The time and location of individual lightning strikes are determined using the BLIDS system, operated by Siemens, which is based on the time-of-arrival principle. Concurrently, spectral polarimetry in the millimetre band – an innovative technique not previously applied in thunderstorm cloud studies – is employed to elucidate the behaviour of various particle types within a radar resolution volume. Spectral polarimetric radar variables are also used to look for vertical alignment of ice crystals that is expected due to electric torque. Due to challenges posed by non-Rayleigh scattering, scattering simulations are carried out to aid the interpretation of spectral polarimetric variables. It is shown that the start of the Mie regime in the Doppler spectrum can be clearly identified by the use of the spectral differential phase. Furthermore, variations in the location of the first Mie minimum across different spectral polarimetric variables may be attributed to different sensitivities of these variables to particle shape and ice fraction. From the results, there is a high chance that supercooled liquid water and conical graupel are present in the investigated thunderstorm clouds. There is also a possibility of ice crystals arranged in chains at the cloud top. Ice crystals become vertically aligned a few seconds before lightning and return to their usual horizontal alignment afterwards. However, this phenomenon has been witnessed in only a few cases of cloud-to-cloud lightning, specifically when the lightning strike is in close proximity to the radar's line of sight or when the lightning is strong. Doppler analyses show that updrafts are found near the core of the thunderstorm cloud, while downdrafts are observed at the edges. Strong turbulence is also observed as shown by the large Doppler spectrum width.

- Article

(12767 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Lightning is the electric discharge caused by an electrical breakdown of charges built up in a cloud. Scientists began investigating atmospheric electrification and lightning several hundred years ago. Many studies have shown that the charge distribution in most thunderclouds follows a tripole structure, with positive charges in the upper and lower levels and negative charges in the middle level (Wang, 2013). The positive charge centre near the cloud base is relatively small and thus is sometimes ignored. Typically, a breakdown can occur when the environmental electric field established by the charges is around 100–300 V m−1, though the critical field at the point of breakdown is likely much higher (Wang, 2013). During a thunderstorm, the electric field builds up and breaks down continuously. The time needed to accumulate large enough electric fields for lightning to occur ranges from less than a minute to several minutes (Gunn, 1954; Marshall and Winn, 1982). For active thunderstorm clouds with tens of kilovolts per metre (kV m−1) in the interior, the magnitude of the electric field decreases to 3 kV m−1 within 5 km away from the cloud edge on average (Merceret et al., 2008).

Over the years, numerous charging mechanisms were proposed to account for charge separation in thunderstorm clouds. These can be divided into three major categories: convective charging, inductive charging, and non-inductive charging. According to the convective charging mechanism proposed by Vonnegut (1955), updrafts carry fair-weather positive charges into the cloud to form a positive charge centre. Negative charges are then attracted to the top and edges of the cloud, which are subsequently brought to the lower level by downdrafts. However, numerous investigators, such as Chiu and Klett (1976), have found inconsistencies between this mechanism and observations, such as opposite cloud polarity if the cloud forms close to the ground. Inductive charging includes different charge separation mechanisms that involve charges induced by the external fair-weather electric field, such as charging by selective ion capture (Wilson et al., 1929), drop breakup charging, and particle rebound charging. However, many studies have shown that these mechanisms are quantitatively unrealistic or ineffective as they are only applicable when the electric field strength is below the typical thresholds required for lightning initiation in thunderstorms (Pruppacher and Klett, 1980; Wang, 2013). For non-inductive charging, charge separation occurs without the presence of an external electric field. Under this category, the most widely accepted mechanism is charging due to the collision of ice crystals with riming graupel pellets, which was first studied in the laboratory by Reynolds et al. (1957). It was found that graupel pellets that are growing by the accretion of supercooled droplets acquire negative charges as they collide with ice crystals. Takahashi (1978) further investigated this phenomenon and found that the magnitude and sign of the electrification depend largely on temperature and cloud water content. The optimal cloud water content for graupel to become highly charged is 1 to 2 g m−3. Graupel will become positively charged if the temperature is above the charge reversal temperature TR, which ranges from −20 to −10 °C, and negatively charged otherwise (Takahashi, 1978). Within the updraft column in a thundercloud, where temperature is below TR, negatively charged graupel and positively charged ice crystals will be formed. The negatively charged graupel will fall at the periphery of the column, where the updraft is weak, while the positively charged ice crystals with negligible fall velocity will be thrown upwards. As the graupel reach a region warmer than TR, they become positively charged, forming the tripole structure of most thunderclouds. Although non-inductive charging due to the collision of graupel and ice crystals best explains tripolar cloud structure, it should be noted that all charging mechanisms above could contribute to certain extent at some time to cloud charging even though these mechanisms alone would produce inadequate or reversed charges (Pruppacher and Klett, 1980).

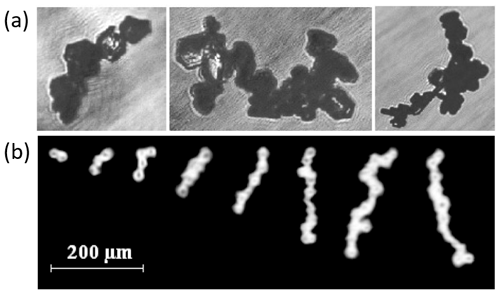

To know what could be observed in thunderstorm clouds, it is important to first identify the ingredients of thunderstorms. A wide variety of ice particles can be found in thunderclouds. Ice crystals of different shapes and sizes can be formed at different temperatures and ice supersaturation (Bailey and Hallett, 2009). These crystals can grow within clouds through three major processes (Pruppacher and Klett, 1980; Lamb and Verlinde, 2011): riming, water vapour diffusional growth, and aggregation. Riming occurs when supercooled water droplets collide with ice crystals and freeze on them, generally resulting in increased particle size, density, and sphericity. Conical graupel can be formed if riming occurs while particles fall through strong updrafts containing water droplets. Since the bottom windward side of the particle grows faster than the top leeward side, the particle develops a conical shape (Tang et al., 2017). Scattering simulations carried out by Oue et al. (2015), and data from the scattering database created by Lu et al. (2016), indicate that conical graupel can produce negative differential reflectivity (ZDR) values at the X, Ka, and W bands. Diffusional growth takes place when water vapour diffuses towards ice crystals from gas phase. During this process, crystals keep their characteristic shape (Lamb and Verlinde, 2011). Aggregation occurs when ice crystals collide with each other and form larger particles that tend to be more spherical in shape. Various lab measurements have demonstrated that when an electric field of more than around 50 kV m−1 is present, the aggregation of ice crystals may be enhanced due to attractive electrical forces induced between neighbouring conducting crystals, forming elongated chains rather than almost spherical clusters (Connolly et al., 2005). The efficiency of this process is the highest at approximately −10 °C according to laboratory studies, but these studies are only conducted at temperatures higher than −20 °C (Connolly et al., 2005). In the atmosphere, chain-like aggregates are observed in convective storms at temperatures below −40 °C (Connolly et al., 2005; Stith et al., 2002). Figure 1a shows some examples of plate crystals arranged into chains in anvil clouds (i.e. the region of convective cloud detraining from the main cell of the thunderstorm cloud) captured by a cloud particle imager taken by Connolly et al. (2005) at an altitude of around 12 km, where the temperature is below −40 °C. Chain-like aggregates can also be formed from frozen droplets, such as those observed by Gayet et al. (2012) near the top of an overshooting convective cloud at 11080 m, where the temperature is −58 °C as shown in Fig. 1b. The enhancement of aggregation starts to decrease when the electric field exceeds 150 kV m−1 since the strong electric field would fragment the ice particle (Connolly et al., 2005). Meanwhile, laboratory experiments have found that electric-field-enhanced aggregation does not occur when the ice particle number concentration is below 2 cm−3 (Wahab, 1974). High concentrations of ice particles could be present in convective clouds if strong updrafts carry supercooled droplets to a level of −37 °C, where they freeze rapidly by the process of homogeneous nucleation (Gayet et al., 2012).

Figure 1Examples of (a) plate crystals arranged into chains in anvil clouds taken by Connolly et al. (2005) (chain lengths from left to right are 381, 632, and 721 µm, respectively) and (b) frozen drops arranged into chains near the top of an overshooting convective cloud taken by Gayet et al. (2012).

Evidence of the presence of graupel and ice crystals in thunderstorm clouds was found using polarimetric and Doppler measurements. Mattos et al. (2016) used X-band radar to compare storms with and without lightning activities and analysed the vertical distribution of hydrometeors within the clouds. They found that in the lower layer of thunderclouds (from 0 to −15 °C) there is an enhanced positive specific differential phase shift (KDP) probably associated with supercooled oblate raindrops lofted by updraft; in the middle layer (from −15 to −40 °C) there is negative ZDR and KDP and moderate horizontal reflectivity, all of which are possibly associated with the presence of conical graupel. With Ka-band cloud radar, Sokol et al. (2020) identified a mixture of hydrometeors at an elevation of 4–7 km (from −6.6 to −27 °C) with a predominance of ice and snow particles and graupel based on the terminal velocities of different hydrometeors. The coexistence of different types of hydrometeors is supported by the measured high Doppler spectrum width.

In addition to the existence of a variety of hydrometeors in thunderstorm clouds, it was first suggested by Vonnegut (1965), based on changes in cloud brightness observed during lightning, that ice crystals would align under a strong electric field. Weinheimer and Few (1987) studied the magnitude of the electric field needed to align particles of different sizes and shapes. They compared the magnitudes of electrical torques that try to align particles' long axis with the electric field and aerodynamic torques that attempt to align particles with their long axes perpendicular to their direction of motion. They estimated that for an electric field of 100 kV m−1, plates with a major dimension smaller than 0.6 mm can be aligned, while the threshold is 1 mm for dendrites and 0.2 mm for thick plates. Columns of all sizes can be aligned by such a field. Meanwhile, only particles smaller than 0.05 mm can be aligned by an electric field of 10 kV m−1. Such alignment of ice crystals is observed in various thunderstorm cases using polarimetric radar measurements. For example, Lund et al. (2009) observed negative ZDR in or near clusters of lightning initiations using S-band radar, while Mattos et al. (2016), using X-band radar, found that in the upper layer (above −40 °C) of thunderclouds, KDP becomes more negative with increasing lightning density. These are likely due to ice particles being aligned vertically by a large vertical electric field. Meanwhile, only one study that used cloud radar to study the alignment of ice crystals during thunderstorms is found. Using a Ka-band radar, Sokol et al. (2020) observed high linear depolarisation ratio (LDR) in clouds that produce lightning in the vicinity, which is likely caused by the canting of ice crystals in an electric field.

Another important ingredient for lightning is strong updraft. According to Zipser and Lutz (1994), lightning is highly unlikely if the mean updraft speed is slower than around 6 to 7 m s−1 or if the peak updraft speed is slower than around 10 to 12 m s−1. Deierling and Petersen (2008) found that time series of updraft volume in the charging zone where the temperature is below −5 °C with vertical velocities exceeding 10 m s−1 is highly correlated to total lightning activity. In general, it is common to find updrafts of more than 10 m s−1 and up to 30 m s−1 in thunderstorms (Stith et al., 2016; Marshall et al., 1995).

Up to this date, most research about thunderstorms made use of S-band (2–4 GHz), C-band (4–8 GHz), and X-band (9–12 GHz) radar, while limited studies were conducted using cloud radar with millimetre wavelength. Radars at lower frequencies are common choices for investigating thunderstorms as they have larger ranges and suffer from less attenuation, but high-frequency cloud radars could bring new insights into thunderstorm clouds before precipitation starts given their higher spatial resolution. Moreover, existing studies of thunderstorms have generally analysed integrated polarimetric radar variables that include the contribution of all particles within each radar resolution volume. Polarimetric Doppler spectra are investigated at the C band in the context of RELAMPAGO field experiment in Argentina in (Aiswarya Lakshmi et al., 2024). However, there have been no attempts to utilise the polarimetric Doppler spectra at millimetre wavelength to disentangle the contributions of different types of particles in thunderstorm clouds. At millimetre wavelength, complications occur because variations in the Doppler spectra can not only indicate another type of particle but also the presence of the Mie scattering regime when the particles grow. This study explores new ways to study thunderstorm events using cloud radar observations and polarimetric Doppler spectra. The goal is to establish links between radar observations and physical processes in thunderstorms to enhance our understanding about lightning.

The work is organised as follows: Sect. 2 provides essential details on the instruments, data, and case study. Section 3 outlines the methodology for conducting spectral polarimetric analysis of thunderclouds, focusing on key radar variables and the scattering simulation used (T-matrix method for spheroids and cylinders). Special attention is given to spectral differential reflectivity (sZDR) and spectral differential backscatter phase (sδco). In Sect. 4, scattering simulation results illustrate how sZDR and sδco vary with ice particle radius, considering factors such as axis ratio, ice fraction, and canting angle. Section 5 applies this background to two thundercloud case studies, emphasising ice particle alignment and notable microphysical properties. Finally, Sect. 6 presents the study's conclusions.

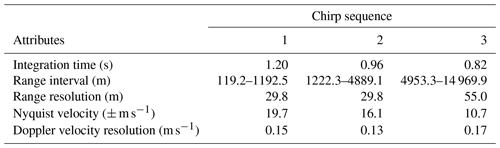

The cloud radar used in this study is a dual-frequency scanning polarimetric frequency-modulated continuous-wave (FMCW) radar produced by Radiometer Physics GmbH located in Cabauw, the Netherlands (51.968° N, 4.929° E). It is named CLoud Atmospheric RAdar (CLARA) and operates at 35 GHz (Ka band) and 94 GHz (W band) in a simultaneous transmission–simultaneous reception (STSR) mode and measures at a constant elevation of 45° and constant azimuth of 282° (see Fig. A1) at some selected periods. Its half-power beam width at 35 GHz is 0.84°, and temporal sampling is 3.59 s. In this study of thunderstorm clouds, only the 35 GHz data are used since there are numerous issues associated with the 94 GHz data, including significant attenuation, less sensitivity at large heights, Doppler aliasing, and complications due to resonance. The configuration parameters for each chirp sequence are shown in Table 1. Note that the maximum range of nearly 15 km corresponds to the maximum height 10.6 km. The transmitted power is continuously monitored, and the radar receiver (including the receiving antenna) undergoes calibration every 6 months using clear-sky calibration. Short-term calibration is provided through periodic Dicke switching. Prior to the semiannual calibration procedure, the hydrophobic antenna radomes are replaced.

The cloud radar provides two types of output data. The Level 0 dataset contains the raw data, which includes the Doppler spectrum at horizontal and vertical polarisations (sZhh and sZvv), as well as the real and imaginary parts of the covariance spectrum between horizontal and vertical polarisations (sChh,vv). The Level 1 dataset contains processed data, including the equivalent radar reflectivity factor (Ze or Zhh), mean Doppler velocity, Doppler spectrum width, differential reflectivity (ZDR), co-polar correlation coefficient (ρhv), specific differential phase shift (KDP), and slanted linear depolarisation ratio (SLDR). SLDR is a proxy for LDR, which can be computed when the radar alternatively transmits horizontally and vertically polarised electromagnetic waves. Since the radar used in this study transmits them simultaneously, only SLDR is available. Compared to LDR, SLDR in the STSR mode loses the direct mean canting angle information due to the inability to acquire cross-polar measurements but retains information on the variance of the canting angles and axis ratios. The radar also has a passive broad band channel operated at a centre frequency of 89 GHz that provides information about the integrated liquid water path (LWP). A weather station is attached, which provides the rain rate, surface wind speed, and wind direction but does not provide the wind profile. The wind profile is obtained instead from European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) Integrated Forecast System (IFS) output over Cabauw (O'Connor, 2022) available at https://cloudnet.fmi.fi/ (last access: 10 May 2023). This model provides hourly forecasts of zonal (eastward) and meridional (northward) wind up to 80 000 m, with a horizontal resolution of 9 km. The model uses an eta coordinate system, with a vertical resolution of the first 10 000 m ranging from around 20 m near the surface to around 300 m at the top. A microwave radiometer beside the radar provides temperature and relative humidity profiles along the zenith. Lightning data are obtained from the online lightning map at https://meteologix.com (last access: 20 June 2023) provided by Siemens BLIDS. The location, time, type, charge (positive or negative), and power of each lightning strike is given.

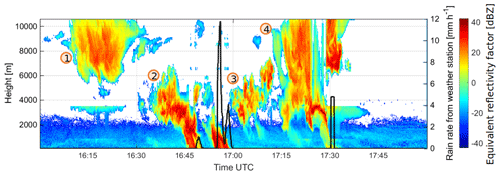

Figure 2Equivalent reflectivity factor on 18 June 2021 16:00–17:59 UTC. Black line shows the rain rate.

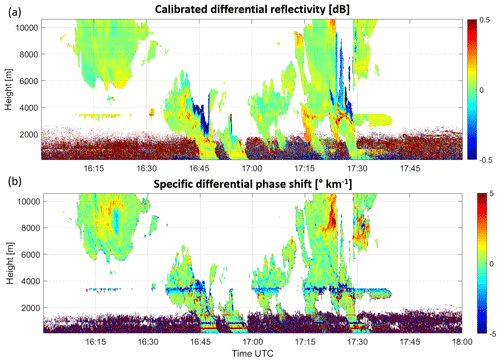

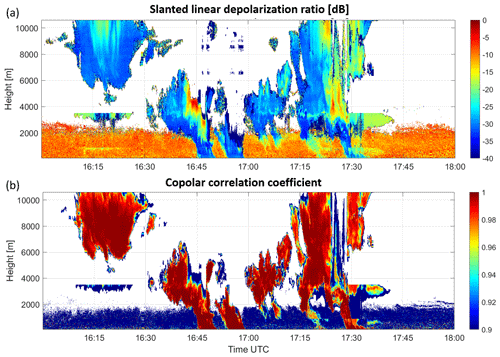

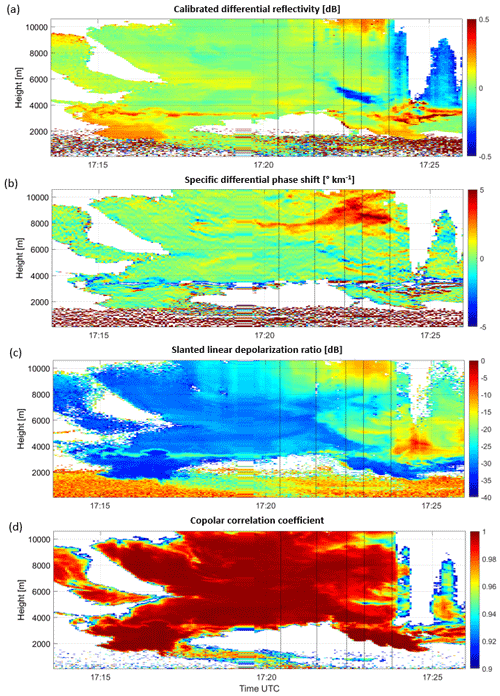

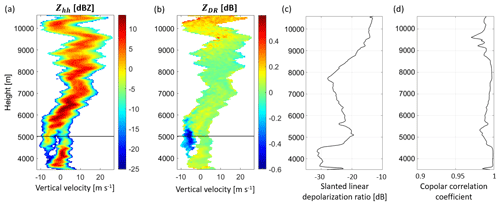

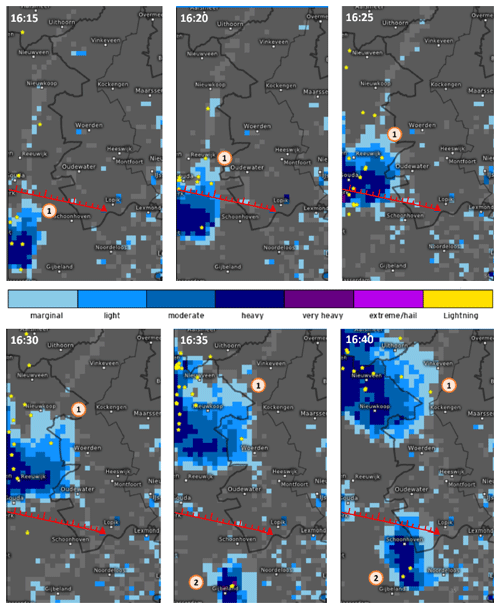

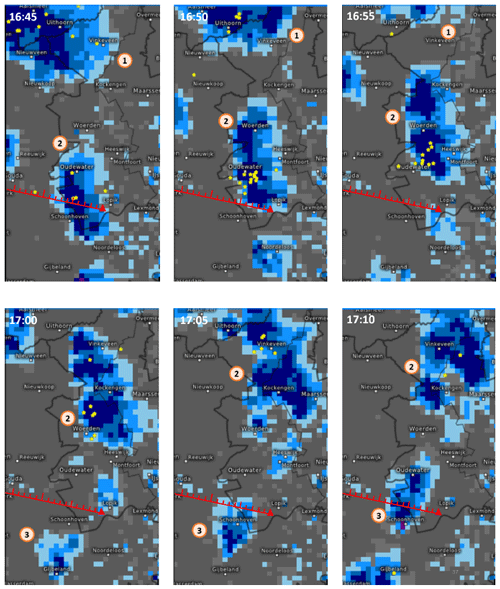

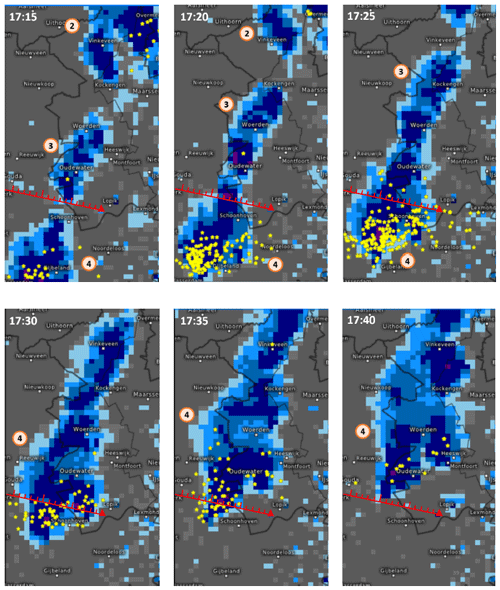

The thunderstorm case being studied took place on 18 June 2021 from 16:15 to 17:45 UTC near Cabauw. The observed thunderstorm was associated with severe weather conditions over the Netherlands, attributed to the remnants of storm “Bill”, and the tropopause height during the event was approximately 12.5 km (Scholten et al., 2023). Four major thunderstorm clouds (numbered in Figs. 2, A1, A2, and A3) crossed the line of sight of the radar from southwest to northeast. The equivalent reflectivity factor, Ze, and rain rate from 16:00 to 17:59 UTC are shown in Fig. 2, while ZDR, KDP, SLDR, and ρhv are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Note that Ze, SLDR, and ρhv are taken directly from the Level 1 files, while ZDR and KDP are re-calculated from Level 0 files and calibrated.

It is evident from Fig. 2 that due to significant attenuation, the top part of the second and fourth clouds which produced precipitation that reached the ground is missing. Some artefacts are observed, such as the noise from ground level to 2500 m over the entire period and the “ghost” signals between 2500 and 3500 m from 16:10 to 16:25 UTC and from 17:30 to 17:40 UTC, which are likely due to signals from the top of the cloud being folded into the second chirp. These artefacts are also present in other variables; thus the data in the second chirp might not be reliable. From Fig. 2, no melting layer with high Ze is visible, even though the temperature was about 0 °C at around 4000 m, which is likely due to convective mixing. However, after 17:15 UTC, a brief indication of a melting layer can be observed using the radar variables, ZDR, SLDR, and ρhv in Figs. 3a and 4.

From Fig. 3a, negative ZDR values are observed from 16:42 to 16:48 and from 17:24 to 17:30 UTC, which could be associated with the alignment of particles near lightning. From Fig. 4b, lower-ρhv values of 0.9 are also found from 16:42 to 16:48 UTC and from 17:24 to 17:30 UTC, which could suggest that there may be a mixture of hydrometeors in the cloud. However, at those times and locations, the decreasing ρhv and increasing SLDR values could be due to a lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) because of the attenuated equivalent reflectivity factor; thus, caution is required when interpreting these values. Also the differential reflectivity may be impacted by rain differential attenuation. Therefore, these times or locations will not be discussed further. Comparing Fig. 3a and b, ZDR and KDP show different patterns in some areas, such as in the first high cloud and in the top part of the cloud from 17:20 to 17:25 UTC. These will be further investigated.

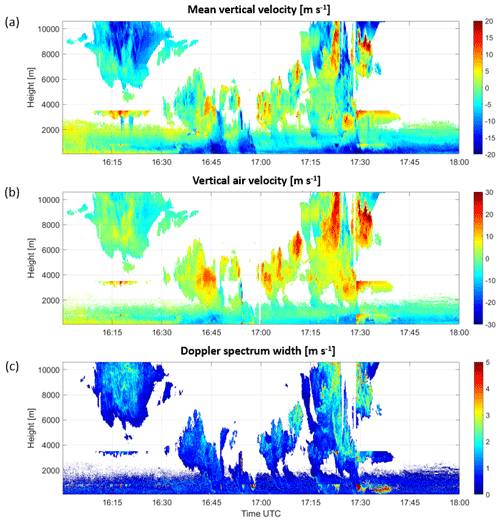

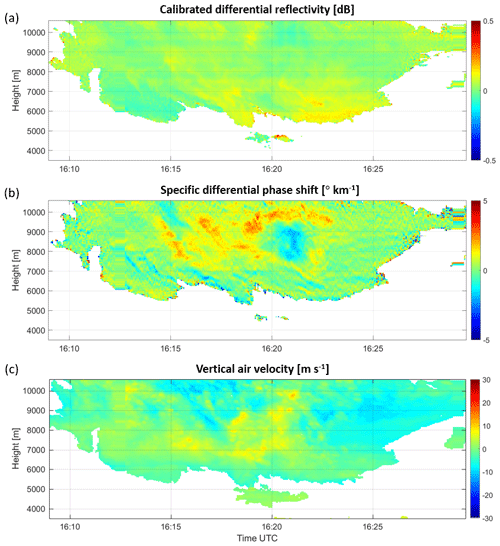

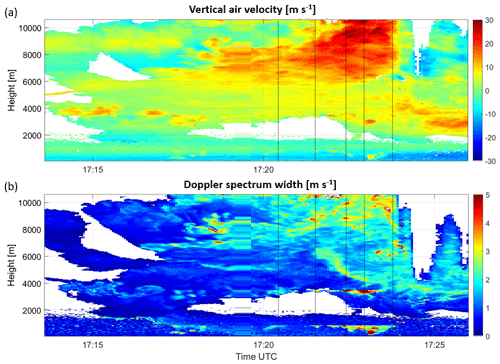

Figure 5(a) Mean vertical velocity, (b) vertical air velocity, and (c) Doppler spectrum width on 18 June 2021 at 16:00–17:59 UTC from 35 GHz radar with 45° elevation.

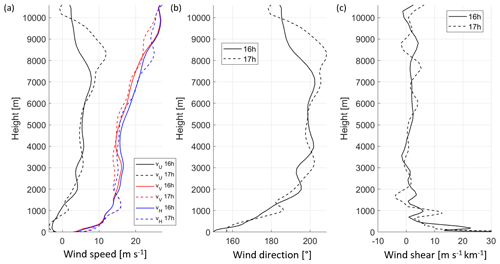

Figure 5 shows the mean vertical velocity, vertical air velocity, and Doppler spectrum width during the thunderstorm. The mean vertical velocity in Fig. 5a eliminates from the measured mean Doppler velocity the contribution of horizontal wind in the same hour obtained from ECMWF model forecast initialised on 17 June 2021 at 12:00 UTC. For such a complex system as a thunderstorm, this leads to a first approximation of the mean vertical velocity of hydrometeors. In the first cloud from 16:10 to 16:30 UTC, particles are mainly falling, while in the other clouds, there are alternate regions where particles are falling and rising. The vertical air velocity is obtained from the Doppler velocity bin corresponding to the smallest particles measured. From Fig. 5b, vertical air velocity varies a lot within the clouds. There are regions with upward velocity exceeding 20 m s−1, which shows there may be strong updrafts in the thunderstorm clouds. There are also adjacent regions with upward and downward motion, such as near 16:22 and 17:20 UTC. These may represent convective motion in the clouds. Figure 5c shows that some regions in the clouds have high Doppler spectrum width, such as within the first cloud and near the top of the fourth cloud. This could mean that there is a wide variety of particles within the radar resolution volume or that the Doppler spectrum is broadened by turbulence or shear (Doviak and Zrnic, 2006; Feist et al., 2019).

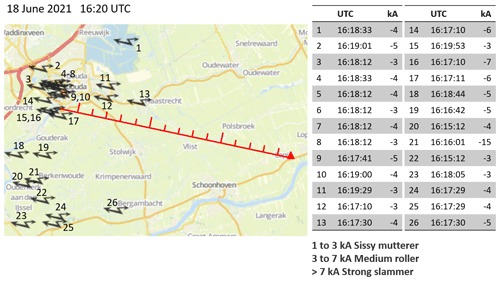

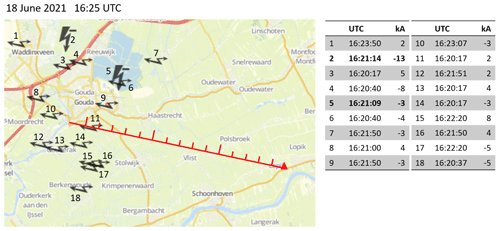

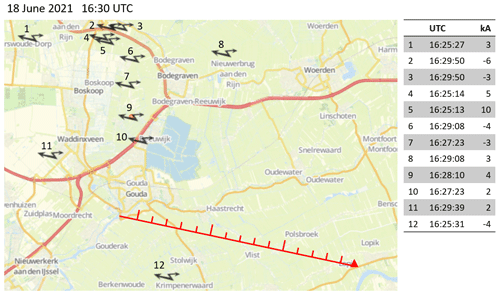

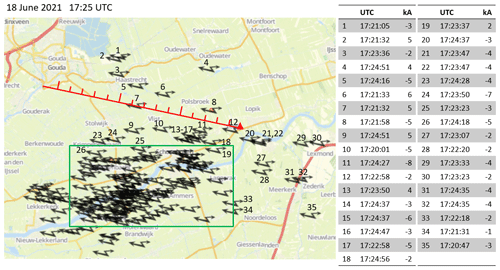

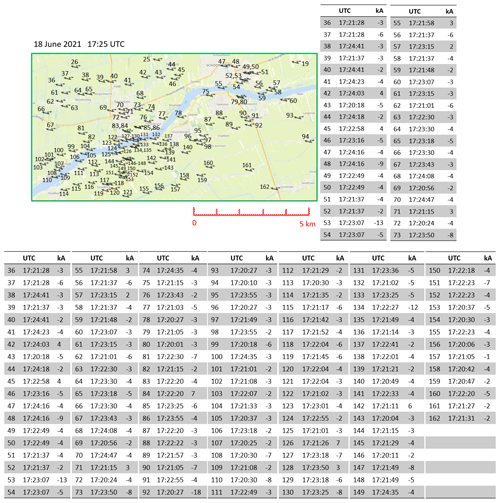

For a better understanding of the cloud radar data, weather radar images from 16:15 to 17:40 UTC are shown in Figs. A1, A2, and A3 (Kachelmann GmbH, 2023). Lightning strikes within 5 min prior to the labelled time are marked by yellow asterisks. The red triangle shows the cloud radar location, and the red ruler shows the line of sight of the cloud radar, with each mark equal to 1 km. Lightning occurred in all four major clouds labelled in Fig. 2. For the first cloud, lightning occurred near the line of sight at more than 10 km away from the radar. For the second cloud, lightning occurred at the ranges 3 to 8 km with a cross-range varying from 1 to 10 km. The third cloud only produced two lightning strikes after passing through the line of sight of the radar. The fourth cloud produced a large number of lightning strikes near the radar line of sight from less than 1 km to more than 15 km along-range. Lightning was most active from 17:15 to 17:25 UTC and became less active as the cloud passed through the line of sight of the radar and moved away.

This section explains the steps required to analyse radar data to investigate thunderstorm events. First, the way to compute polarimetric and Doppler variables from raw data is explained in Sect. 3.1. Then, Sect. 3.2 explains how integrated variables and Doppler spectra were used to investigate properties of the thunderstorm clouds. Finally, Sect. 3.3 explains the motivation and method of performing scattering simulations.

3.1 Radar variables

3.1.1 Polarimetric variable calculation

This research utilised spectral polarimetric radar variables derived directly from the Level 0 data. Consequently, the majority of the integrated radar variables were also computed from Level 0 data. This approach facilitates consistency checks between Level 0 and Level 1 data, enables spectral domain filtering when necessary, and allows for the dealiasing of Doppler spectra prior to the calculation of Doppler moments.

The integrated ZDR and ΨDP (differential phase shift) can be computed by

The covariance spectrum sChh,vv corresponds to the Level 0 array CHVSpec. The minus sign in Eq. (2) is added in order to obtain the right trend for KDP in rain, namely positive at 35 GHz and negative at 94 GHz. Here, r is the range, v is the Doppler velocity, and t is the time. Only data with signal-to-noise ratio above 10 dB were included in the summations to be consistent with the analysed spectral data.

The spectral differential reflectivity (sZDR) and spectral differential phase shift (sΨDP) can be computed by

Only the part of the spectra with signal-to-noise ratio above 10 dB was used to exclude the noisy edges of the spectra, where values often fluctuate significantly (Yu et al., 2012). In addition, the spectra were smoothed using a five-point moving average in Doppler bin to reduce noise. For this study, an extra polarimetric calibration was carried out using vertical profiles of precipitation involving high precipitating clouds. This procedure resulted in reducing the expected error associated with ZDR and ΨDP from 0.18 to 0.05 dB and from 1.6 to 0.6°, respectively.

The SLDR and ρhv values were taken from the Level 1 dataset.

The specific differential phase shift (KDP) was approximated from the calibrated ΨDP in degrees in two steps. First, ΨDP was smoothed using a five-point moving average in range to reduce noise. Then, KDP was computed by

where Δr is the distance between adjacent range bins in kilometres. Note that this quick estimation of the specific differential phase shift is meant for detecting areas of interest in thunderstorm cloud profiles. For quantitative values of KDP, this processing may be too simple when large-sized ice particles are present in the thunderstorm cloud and non-Rayleigh scattering occurs.

3.1.2 Doppler variable calculation

The measured Doppler velocity v of a particle, defined as negative as the particle approaches the radar, is given by

where w is the vertical air velocity, vH is the horizontal wind speed, Vt is the terminal fall velocity of the particle (positively defined), and θ is the elevation angle of the radar. D is the wind direction, and ϕ is the azimuth angle of the radar beam, with both being relative to true north. The mean Doppler velocity can reflect the average motion of particles in a radar resolution volume along the line of sight of the radar. To extract it from Level 0 data, the first step is to unfold and de-alias each Doppler spectrum. Then, the mean Doppler velocity () can be computed by

The Doppler spectrum width () can also be computed by

The mean vertical velocity () can give information about the vertical motion of hydrometeors in thunderstorm clouds. It can be estimated by solving Eq. (6) using the mean Doppler velocity () together with vH and D estimated from the ECMWF model data.

It is also useful to extract the vertical air velocity, which can give information about the updraft and downdraft patterns in thunderstorm clouds. It can be estimated by assuming that the smallest particles in the Doppler spectra are so light that their fall velocity is very close to zero; thus, their vertical velocity is equal to the vertical air velocity. Therefore, the first step is to identify the Doppler velocity of the bin with the highest Doppler velocity value in the Doppler spectra with a 10 dB SNR threshold. Then, the vertical air velocity w can be estimated by solving Eq. (6) with Vt=0 and vH and D estimated from the ECMWF model data. The latter estimation may influence the accuracy of vertical air velocity measurements. The ECMWF model supplies an average horizontal wind profile, whereas the cloud radar observations are associated with thunderstorm clouds, where local dynamic variability is anticipated.

3.2 Analysing radar variables

3.2.1 Analysing integrated variables

Integrated variables were used in this study to identify time instants and ranges where signals related to lightning activities are present. During lightning, the electric field in clouds can align ice crystals vertically, causing ZDR and KDP to become negative. When negative ZDR or KDP is observed in the integrated profile, more in-depth analyses were carried out by investigating sZDR and sΨDP at those time instances to understand the causes of those negative values.

Other useful variables may be the linear depolarisation ratio (LDR) and the co-polar correlation coefficient (ρhv). High LDR values may indicate the canting of ice crystals in a specific direction due to cloud electrification (Sokol et al., 2020). With regard to SLDR, areas with low values may result from a reduction in the canting angle variance caused by the alignment of ice particles. Regions with low ρhv could be regions where graupel and ice crystals co-exist, and they may collide with each other to produce an electric field. However, when the SNR is low, SLDR and ρhv values may become large and low, respectively, regardless of the characteristics of the particles. Therefore, analysis was made at sufficient SNR, which is above 10 dB.

3.2.2 Analysing Doppler spectra

While integrated variables contain information about all particles within a radar resolution volume, Doppler spectra separate the contributions of particles with different Doppler velocities and hence different sizes or densities. With spectral ZDR, it would be possible to identify whether negative ZDR is contributed by small particles that would appear in the right part of the Doppler spectrum or by large particles that would appear in the left part of the Doppler spectrum. If negative ZDR is observed for small particles, it is likely that an electric field is present that aligns the small particles. On the other hand, based on the database described by (Lu et al., 2016), negative ZDR for large particles only may indicate the presence of conical graupel. However, the possible transition from the Rayleigh to Mie scattering regime may complicate these interpretations of spectral ZDR.

The vertical gradient of the differential phase shift (ΨDP) is related to KDP. A positive gradient indicates positive KDP, and vice versa. With the use of sΨDP the Mie scattering regime can be identified. As mentioned before, fluctuations in sZDR values in the Mie scattering regime make it difficult to interpret those values. It is therefore crucial to identify when the Mie scattering regime begins. This is done by making use of the following relationship between differential phase shift (ΨDP), the two-way differential propagation phase (ΦDP), and the differential backscatter phase (δco): .

In the Rayleigh scattering regime, where δco is zero, the spectral differential phase shift at a fixed range remains constant because the electromagnetic wave at both polarisations has passed through the same particles in all preceding ranges. This part of the spectrum is often referred to as the Rayleigh plateau (Unal and van den Brule, 2024). In the Mie scattering regime, δco is non-zero and depends on the particle properties; thus, the differential phase shift spectrum is no longer flat. Therefore, the Mie scattering regime begins when the left part of the differential phase shift spectrum starts to increase or decrease. The effect of noise may sometimes affect the identification of the Mie scattering regime. It is useful to know that the maximum or minimum values of spectral ΨDP are often aligned with the maximum or minimum values of spectral ZDR. Thus, if the maxima or minima of sΨDP and sZDR are aligned, one can be more confident that the fluctuations observed are due to resonance instead of noise.

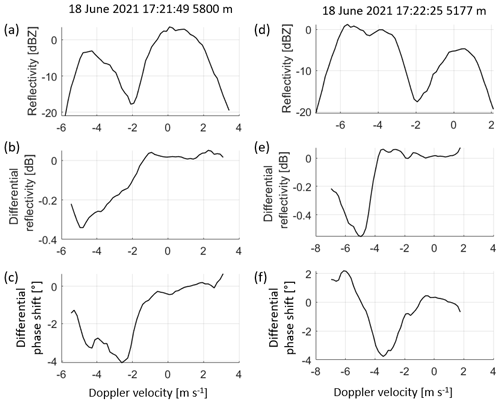

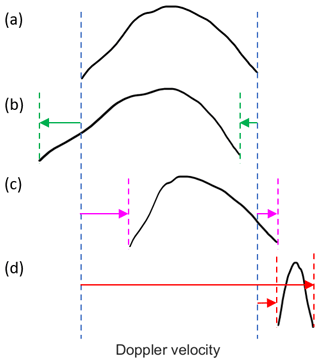

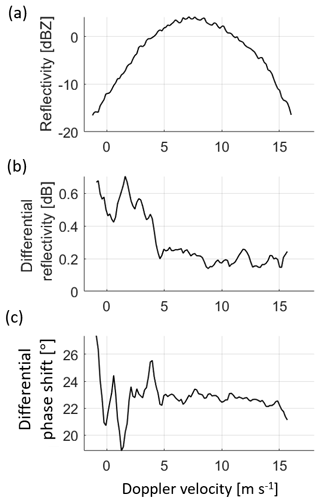

The left column of Fig. 6 shows an example of where the Mie scattering regime can be clearly identified using sΨDP. The Rayleigh plateau is found from −1 to 3 m s−1, while non-Rayleigh scattering occurs at Doppler velocity smaller than −1 m s−1 since sδco becomes non-zero. sZDR follows a similar trend, which strengthens the proof that non-Rayleigh scattering occurs. However, some cases can be more tricky, such as the one shown in the right column of Fig. 6. Here, the Rayleigh plateau ends at about −0.5 m s−1, while sZDR only begins to decrease at about −4 m s−1. To understand this better, scattering simulations are needed, which are discussed next.

3.3 Scattering simulations

Studying the Doppler spectrum of ZDR is challenging when resonance is involved. This is because sZDR values fluctuate in the Mie scattering regime, so it will become difficult to determine whether the fluctuations in the observed ZDR spectrum are due to changes in the shape or density of hydrometeors or resonance. Therefore, scattering simulations were carried out to understand how non-Rayleigh scattering affects the ZDR spectrum using the Python code PyTMatrix (Waterman, 1965; Leinonen, 2014). The code is based on the T-matrix method (Waterman, 1965), which is a numerical model of electromagnetic and light scattering by non-spherical particles with sizes comparable to the wavelength of the incident radiation. The code supports simulations of spheroids or cylinders. The scattering matrix of a scatterer depends on several parameters, including the axis ratio, ice fraction, and canting angle. The axis ratio is defined as the length along the scatterer's rotational axis to its width perpendicular to this axis. It is smaller than 1 for oblate particles and larger than 1 for prolate particles. Ice fraction (fi) characterises how much ice and air a scatterer is composed of, which affects the density of the particle. A value of 1 means pure ice, while a value of 0 means pure air. Ice fraction affects the complex effective relative permittivity of the scatterer (εeff). One approximation is given by the Maxwell–Garnett formula as follows:

where εi is the complex relative permittivity of ice. The value of εi is 3.19015+0.00285i at 35 GHz at 266 K, and the temperature dependence is small for the part of the spectrum from ultraviolet (175 nm) to the microwave (1 cm) (Warren and Brandt, 2008). The complex effective refractive index of the scatterer (meff), which is a parameter that can be specified in the simulation code, can then be determined using

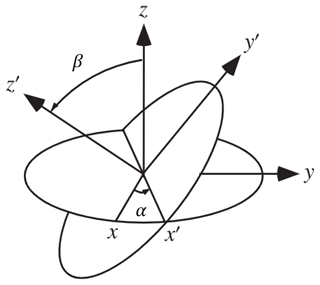

The canting angle refers to the Euler angle β of the scatterer defined in Fig. 7.

Figure 7Definition of Euler angles α and β. The xyz coordinate frame has the z axis aligned with the radar's zenith direction. The rotated frame is denoted as , corresponding to the particle's orientation. Starting from the xyz frame, a rotation by angle α around the z axis results in the intermediate frame x′y1z. This is followed by a rotation by angle β around the x′ axis to achieve the final frame.

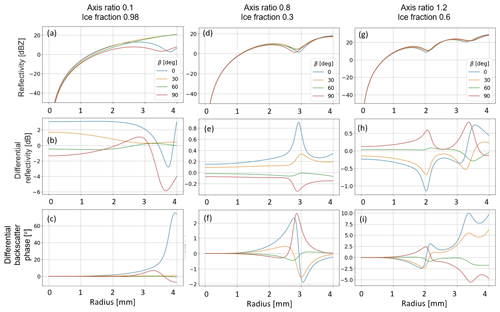

In the simulation, a scatterer object in the shape of a spheroid was defined, and the backscatter radar reflectivity (Ze), differential reflectivity (ZDR), and differential backscatter phase (δco) at 35 GHz, with a 45° looking angle, were retrieved. The axis ratio and ice fraction of the particles in the simulation experiments were chosen according to the data given in Spek et al. (2008). In the first experiment, the axis ratio of spheroids with a zero mean canting angle was varied from 0.1 to 1.2. This range encompasses the axis ratios of plates, dendrites, aggregates, and graupel. The ice fraction was held constant at 0.6, representing the average ice fraction for the aforementioned ice particles. In the second experiment, the ice fraction of spheroids with a zero mean canting was varied from 0.2 to 1, which covers the ice fraction range of plates, dendrites, aggregates, and graupel. Simulations for both oblate and prolate particles were carried out, with an axis ratio of 0.8 or 1.2. In the third experiment, the canting angle was varied from 0 to 90°. Three sets of simulations were carried out to simulate different types of particles, including plates (axis ratio = 0.1; ice fraction = 0.98), slightly oblate aggregates (axis ratio = 0.8; ice fraction = 0.3), and graupel (axis ratio = 1.2; ice fraction = 0.6). For all simulations, the canting angles of the spheroids follow a Gaussian distribution with a standard deviation of 0.1°. The Euler angle α of the scatterers (see Fig. 7) follows a uniform distribution from 0 to 360°.

Note that the T-matrix method (Leinonen, 2014) offers flexibility for simulating the radar spectral variables by varying different input parameters (axis ratio, ice fraction, and Euler angles) for a first examination of trends at 35 GHz. Nonetheless, this method has limitations as it assumes that ice particles are spheroidal and have a fixed ice fraction or density. It ignores the non-homogeneity of ice particles, especially aggregates, which may result in a bias in the spectral polarimetric variables when the frequency increases. This is another reason to carry out this study of thunderstorm clouds at 35 GHz but not at 94 GHz.

This section gives an overview of the dependencies of spectral polarimetric radar variables of particles, sZhh, sZDR, and sδco, on the axis ratio, ice fraction, and canting angle in the Rayleigh and Mie scattering regimes based on scattering simulations.

4.1 Axis ratio

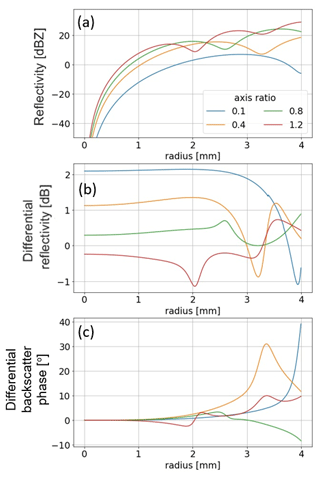

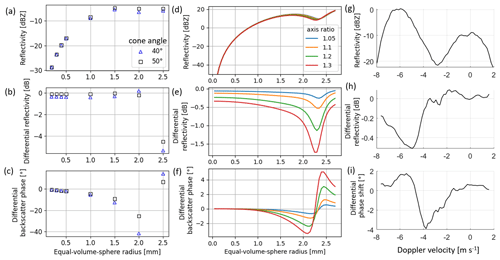

Figure 8 shows the simulation results for spheroids with the ice fraction 0.6 and zero mean canting angle with different axis ratios at 35 GHz. The radius refers to the maximum radius of the spheroid, i.e. half the length of its long axis. From Fig. 8a, the first Mie minimum occurs at a maximum radius of around 2 mm for axis ratio 1.2, 2.6 mm for axis ratio 0.8, and 3.2 mm for axis ratio 0.4. Therefore, for oblate spheroidal particles, the position of the first Mie minimum goes towards a larger radius when axis ratio decreases.

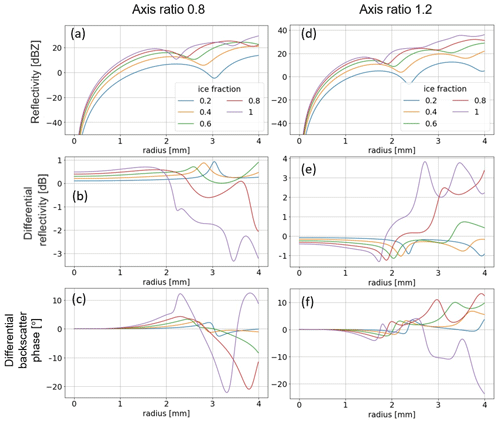

Figure 9Simulated radar variables for spheroids with a zero mean canting angle and different ice fractions as a function of maximum radius at 35 GHz with a 45° looking angle. Panels (a)–(c) show the radar reflectivity, differential reflectivity, and differential backscatter phase for spheroids with fixed axis ratio of 0.8. Panels (d)–(f) show the same for spheroids with fixed axis ratio of 1.2.

From Fig. 8b, in the Rayleigh scattering regime, ZDR decreases with an increasing axis ratio, with positive values for oblate spheroids (axis ratio < 1) and negative values for prolate spheroids (axis ratio > 1). When entering the Mie scattering regime, ZDR of oblate particles increases slightly, while that of prolate particles decreases. At the first Mie minimum, particles with an axis ratio of 0.1, 0.4 and 1.2 give a trough in ZDR, but those with an axis ratio of 0.8 give a peak. In addition, the lines for different axis ratios cross over each other in the graph of ZDR, meaning that the trend between ZDR and the axis ratio depends on particle size. From Fig. 8c, δco of oblate particles increases when entering the Mie scattering regime and gives a peak at the first Mie minimum, while that of prolate particles decreases and gives a trough.

4.2 Ice fraction

Figure 9 shows two sets of simulations for spheroids with a zero mean canting angle and different ice fractions. The Mie minima can be seen in the reflectivity plots (Fig. 9a, d). For oblate and prolate spheroids, the position of the first Mie minimum goes towards larger radius when ice fraction decreases. In the Rayleigh scattering regime, the magnitude of ZDR increases with an increasing ice fraction. The first extremum of ZDR is attained at a smaller size for spheroids with a higher ice fraction. For a low ice fraction (0.2, 0.4, and 0.6), the sign of ZDR does not change after entering the Mie scattering regime (except for radius larger than 3.2 mm for spheroids with an axis ratio of 1.2 and an ice fraction of 0.6). When the ice fraction is large (0.8 and 1), the sign of ZDR flips soon after reaching the first extremum, and the trend is rather unpredictable. For particles of this ice fraction with a radius larger than 2.5 mm, which could represent graupel, significant negative (positive) values could be obtained, which increases the interpretation challenge. The differential backscatter phase initially increases (decreases) for oblate (prolate) particles when entering the Mie scattering regime. The sign reverses afterwards, and the trend becomes less predictable, especially if ice fraction is high.

Figure 10Simulated radar variables for spheroids with different canting angles as a function of maximum radius at 35 GHz with a 45° looking angle. Panels (a)–(c) show the radar reflectivity, differential reflectivity, and differential backscatter phase for spheroids similar to plates with fixed axis ratio of 0.1 and ice fraction of 0.98. Panels (d)–(f) show the same for spheroids similar to slightly oblate aggregates, with a fixed axis ratio of 0.8 and an ice fraction of 0.3. Panels (g)–(i) show the same for spheroids similar to conical graupel with a fixed axis ratio of 1.2 and an ice fraction of 0.6.

4.3 Canting angle

Figure 10 shows three sets of simulations for spheroids with different canting angles. The Mie minima can be seen in the reflectivity plots (Fig. 10a, d, g). A zero mean canting angle corresponds to oblate spheroids being horizontally aligned and prolate spheroids being vertically aligned. To represent prolate particles as horizontally aligned, they are modelled with a mean canting angle of 90°.

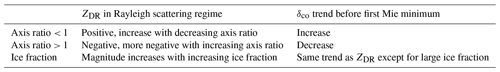

Table 2ZDR characteristics in Rayleigh scattering regime and trend of δco before first Mie minimum. The mean canting angle of the spheroids is zero.

Figure 11(a) Differential reflectivity, (b) specific differential phase shift, and (c) vertical air velocity of the first thunderstorm cloud on 18 June 2021 from 16:09 to 16:30 UTC.

For oblate particles (left and middle columns), ZDR in the Rayleigh scattering regime is negative when the canting angle becomes larger than 45°. One can understand this to be the effective axis ratio of an oblate spheroid getting larger than 1 when it becomes vertically aligned. The opposite is true for prolate particles. However, in the Mie scattering regime, the relationship between the sign of ZDR and the canting angle is not trivial. For spheroids similar to plates with an axis ratio 0.1 of and an ice fraction of 0.98, the first extremum of ZDR is positive for β=90° but negative for β=0°. There is no sharp extremum for β=30° or 60°. For spheroids similar to conical graupel with an axis ratio of 1.2 and an ice fraction of 0.6, the sign of ZDR also changes when particle size becomes larger. The differential backscatter phase does not have a trend that can be easily summarised for different canting angles for all three cases. In all instances, the most pronounced resonance patterns are found at canting angles of β=0° and β=90°.

4.4 Summary

In this section, the effects of the axis ratio, ice fraction, and canting angle of spheroids on ZDR and δco are investigated. Table 2 summarises the key trends of ZDR in the Rayleigh scattering regime and the trend of δco before the first Mie minimum for spheroids with different axis ratios and ice fractions. Their mean canting angle is zero. Changing the canting angle has similar effect to altering the axis ratio of the spheroids in terms of the initial trend of ZDR. In general, the sign of ZDR is the same as the sign of δco before the first Mie minimum. However in some cases, δco shows a sign inversion at the first Mie minimum. The fluctuations of ZDR and δco after the first Mie minimum are difficult to predict and often involve sign changes. The most unpredictable behaviours are found when the ice fraction is high.

Furthermore, in Figs. 8–10, there are variations in the location of the first Mie minimum across Zhh, ZDR, and δco, which may be attributed to different sensitivities of these variables to the particle shape, ice fraction, and canting.

From this first analysis, our investigation of spectral polarimetric variables in thunderstorm clouds will start by identifying the Rayleigh scattering part of the spectrum using the measurement of the spectral differential phase. In the Rayleigh scattering regime, the spectral differential backscatter phase is zero, and the spectral differential phase equals the spectral differential propagation phase. This will prevent the misinterpretation of variations in spectral differential reflectivity caused by resonance. Next, focus will be given to the sZDR signature in the Rayleigh scattering regime. Subsequently, analysis can be conducted using sZDR and sδco within the Mie scattering regime, at least up to the first Mie minimum. Second extrema are challenging to interpret and measure, especially at high altitudes, where the signal-to-noise ratio is low.

For each sub-figure, simulations were conducted considering a single type of ice particle. However, in practice, a radar resolution volume may contain multiple types of ice particles, resulting in the final spectral polarimetric variables being composed of different modelled curves as a function of the radius range.

This section discusses interesting observations in the thunderstorm event on 18 June 2021 from 16:15 to 17:45 UTC near Cabauw. Focus has been given to the first and the fourth cloud that passed through the line of sight of the radar. The second cloud was not investigated as the radar suffered from significant attenuation due to the precipitation, while the third cloud was not studied as it only had two lightning strikes after it passed through the line of sight of the radar.

5.1 First cloud

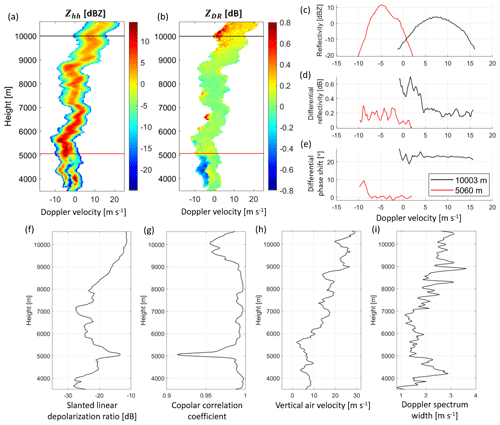

The first cloud came within the sight of the radar from 16:10 to 16:30 UTC. The weather radar images presented in Fig. A1 indicate heavy precipitation occurring at a distance of 10–15 km from the radar between 16:20 and 16:25 UTC. Correspondingly, owing to its 45° elevation angle, the cloud radar observes the thundercloud at altitudes between 6 and 10 km and not the precipitation below.

5.1.1 Alignment of particles

From Fig. 11a and b, intriguing polarimetric signatures can be observed within the cloud. Figure 11a illustrates that ZDR values are near-zero with minimal variation. Conversely, Fig. 11b reveals a cluster of negative KDP values between 7600 and 9300 m and within the time period from 16:20:11 to 16:21:37 UTC, suggesting the alignment of non-spherical small ice particles. If these small ice particles are present in sufficient concentration, KDP would become negative. The large ice particles, on the other hand, are expected to be slightly non-spherical, which leads to a small contribution to KDP, and may not align with an electric field unless it is sufficiently strong. Because ZDR is reflectivity-weighted, large ice particles significantly influence ZDR, which likely explains why ZDR does not exhibit significant negative values.

From Fig. 11c, downdrafts occur in the first cloud from 16:15 to 16:18 UTC and after 16:22 UTC. In these periods, the radar was looking at the edge of the thunderstorm cloud. Therefore, the radar did not see regions with strong updrafts that are normally found in the core of thunderstorm clouds but observed downdrafts outside the core instead. From 16:18 to 16:22 UTC, updrafts of up to 12 m s−1 are observed, which could be because the core of the thunderstorm cloud is closer to the line of sight of the radar. The estimated vertical air velocity is not uniform within the cloud, which suggests that there might be a lot of turbulence. Cloud observations between 6 and 10 km height generally show good agreement with the precipitation patterns and intensity measured by the weather radar at lower heights in Fig. A1. However, timing differences of the order of 1 min may arise due to the differing temporal resolutions of the two radars.

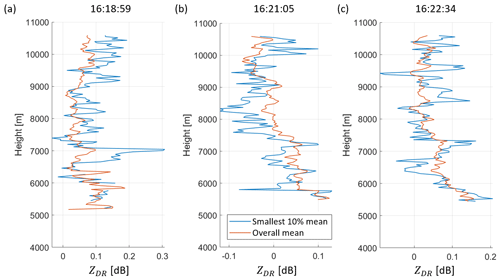

Figure 13Mean sZDR of all particles and the smallest 10 % of the particles in a radar resolution volume on (a) 18 June 2021 at 16:18:59 UTC, (b) 16:21:05 UTC and at (c) 16:22:34 UTC.

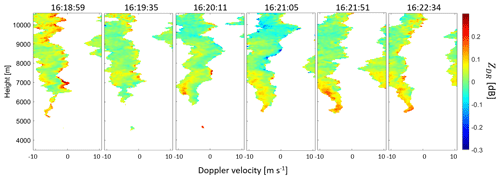

Figure 12 shows the spectral ZDR across the period when negative KDP is observed (panels 3–4). At 16:18:59 UTC, the right part of the spectrum, which corresponds to small ice particles, has positive sZDR, suggesting that the particles are horizontally aligned. However, at 16:21:05 UTC, the right part of the spectrum becomes slightly negative, suggesting that small ice particles are vertically aligned. At 16:22:34 UTC, sZDR of the right part of the spectrum becomes positive again, which suggests that the particles return to being horizontally aligned. Figure 13 shows the mean sZDR of the smallest 10 % of the particles in each radar resolution volume at the three time instants. This is achieved by averaging sZDR over the rightmost 10 % of the Doppler bins. It is clear that from 7000 to 9000 m, sZDR of the smallest 10 % particles is positive at 16:18:59 UTC and 16:22:34 UTC and is negative at 16:21:05 UTC. The question is as follows: are these negative sZDR values associated with cloud electrification before lightning?

Our expectation is that particles align vertically before a lightning strike and return to horizontal alignment afterwards. The lightning strikes closest to the line of sight of the radar that occurred at 16:20:17, 16:21:50, and 16:22:20 UTC (strike numbers 9, 11, and 14–17 in Fig. B2), and negative KDP is observed continuously from 16:20:11 to 16:21:37 UTC. Negative KDP values are observed within the height range of 7600 to 9300 m, whereas the lightning strikes occurred at least 13 000 m away from the radar. If the electric field that caused these lightning strikes is responsible for the alignment of particles observed, one would expect to observe negative KDP value also for heights beyond 9000 m. Making a closer inspection with spectral ZDR, negative sZDR values smaller than −0.1 dB are found beyond 9000 m from 16:20:21 to 16:21:15 UTC (Fig. 16b), though more negative sZDR values are found on the left side of the spectrum that corresponds to large particles instead of the right side as expected (e.g. 16:21:01 UTC in Fig. 16b).

The first question is whether wind shear could be responsible for flipping the Doppler spectrum, causing lighter particles to appear on the left. By modifying the formulation of Wang et al. (2019) to incorporate vertical wind velocity, the horizontal and vertical particle velocities can be expressed as

where vH is the horizontal wind speed, w the vertical wind, is the constant vertical wind shear, g is the gravitational acceleration, and Vt is the terminal velocity of the particle. For a radar looking at elevation θ and azimuth ϕ, the Doppler velocity is . Without shear, the spectrum shifts uniformly by vH and w, leaving lighter particles on the right. When Vt increases, a negative shear s causes the spectrum to widen as the left side shifts more than the right (Fig. 14b), while the positive shear narrows it (Fig. 14c). If the rightward shift on the left due to the term exceeds the original spectrum width, then the spectrum could flip (Fig. 14d).

Figure 14A figure to illustrate the effects of the sign of vertical wind shear s on the Doppler spectrum. (a) Doppler spectrum when there is no shear. (b) Doppler spectrum widens when s is negative. (c) Doppler spectrum may become narrow when s is positive. (d) Doppler spectrum may flip when s is positive and when is larger than the original spectrum width.

For a spectrum width of 10 m s−1 and a terminal velocity (Vt) of 2 m s−1, corresponding to the upper bound for plate-like particles (Spek et al., 2008), a shear of approximately 25000 m s−1 km−1 would be required to invert the spectrum. This value is substantially higher than the observed shear of 4 m s−1 km−1 between 7500 and 10 000 m in ECMWF data, as shown in Fig. 15c. While recognising the limitations of ECMWF wind shear data in the context of thunderclouds, a wind shear of 25 000 m s−1 km−1 is highly improbable. Therefore, wind shear is unlikely to account for the negative sZDR observed on the left side of the spectrum.

Alternatively, the hypothesis is that the axis ratios of small particles are close to one and that the electric fields could align larger particles vertically, leading to negative sZDR on the left side of the Doppler spectrum. However, the most negative sZDR value at 16:21:05 UTC does not coincide directly with lightning, suggesting that the electric field had either weakened or moved out of the radar view by the time of the strikes.

Negative sZDR values on the right edge of the spectra between 7500–9000 m, similarly, do not align with lightning events occurring at cross-ranges larger than or equal to 13 km as significant electric fields extend only about 5 km in thunderstorms (Merceret et al., 2008). Though a strike at 16:21:50 UTC (strike 7 in Fig. B2; cross-range 11 km) may have contributed, this is difficult to confirm due to the unknown electric field variation. The subsequent strike at 16:29:08 UTC (strike number 8 in Fig. B3; cross-range 11.5 km) is too delayed, considering the common duration of charging cycles (Gunn, 1954; Marshall and Winn, 1982), to be connected to earlier negative sZDR values.

Wind-shear-induced particle canting (Brussaard, 1976) is another potential cause. The canting angle of particles due to vertical wind shear, i.e. difference in horizontal wind speed in vertical direction, is given by

The equation holds, assuming a linear wind profile, no updraft, and that the mean orientation of the particles rotational symmetric axes is parallel to the direction of the airflow around them (Brussaard, 1976). Using the vertical shear m s−1 km−1 = 0.004 s−1 and terminal velocity of 2 m s−1, the canting angle is estimated at 0.05°, which is negligible. Even considering underestimation due to model resolution, achieving significant canting would require a much higher shear of 4.9 s−1, making wind shear an unlikely cause of the observed negative sZDR values. Additionally, turbulence is not expected to disrupt ice crystal orientation in cumulonimbus clouds (Cho et al., 1981).

In conclusion, the vertical alignment of particles observed in the first cloud could be due to electric field, though the electric field may not be strong enough to trigger lightning, or there are lightning strikes that are not measured by the lightning sensor.

5.1.2 Interesting microphysical properties

Supercooled liquid water

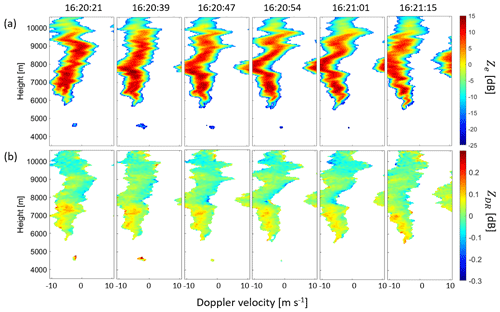

Another interesting feature observed in this cloud is the possible presence of supercooled liquid water. From 16:20:21 to 16:21:15 UTC, spectrograms of reflectivity show a separate mode of particles on the right side of the spectrum at around 6000 m (see Fig. 16a), where air temperature measured by the microwave radiometer is around −12.5 °C. From Fig. 16b, sZDR of this mode of particles is close to zero. This separate mode is most clearly discernible in the fourth panel.

Figure 16(a) Spectral reflectivity and (b) spectral ZDR on 18 June 2021 from 16:20:21 to 16:21:15 UTC showing presence of supercooled liquid water near 6000 m.

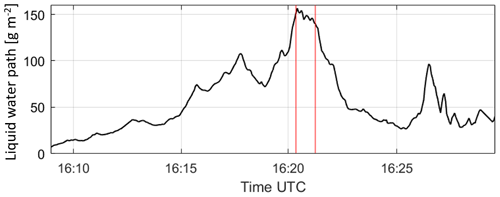

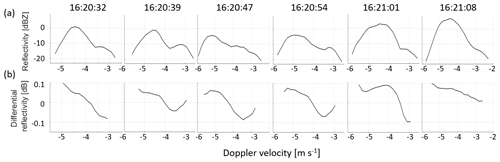

Figure 17(a) Spectral reflectivity and (b) spectral ZDR on 18 June 2021 from 16:20:32 to 16:21:08 UTC at 5916 m.

Figure 17 shows the time series of spectral reflectivity and spectral ZDR at 5916 m. A small peak at a Doppler velocity of around −4 to −3 m s−1 is consistently present. The sZDR of this mode of particles is lower than the left part of the spectrum, with values of around −0.1 to 0 dB. By manually identifying the part of the Doppler spectrum that may contain supercooled liquid water for 139 range bins over 16 time steps, it was found that the average sZDR is −0.0370 dB. Since the error in ZDR after calibration is 0.05 dB and supercooled liquid water droplets are nearly spherical and have a differential reflectivity of 0 dB, there is a high chance that supercooled liquid water is indeed present in the cloud. This is further supported by the liquid water path measured by the cloud radar with a passive channel that has the same looking direction as the radar. From 16:20:21 to 16:21:15 UTC (marked by the red lines in Fig. 18), there is indeed a peak in the liquid water path, which agrees with the hypothesis that supercooled liquid water may be present in the cloud. Supercooled liquid water plays a role in the non-inductive charging mechanism as it is needed for riming to occur, which in turn forms graupel that collides with ice crystals to produce charges. Nonetheless, the radar was not able to look at the lower part of the cloud; thus it is unknown whether graupel is formed in this case.

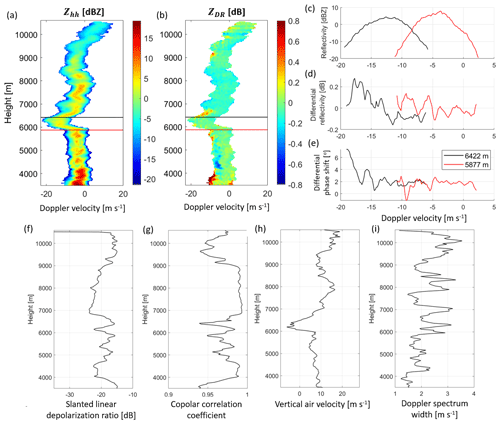

5.2 Fourth cloud

The fourth cloud came within the sight of the radar from 17:15 to 17:40 UTC. The part of the cloud that passed through the line of sight of the radar from 17:15 to 17:20 UTC did not contain active lightning activities. From 17:20 to 17:35 UTC, the part of the cloud with the most active lightning activities passed through the line of sight of the radar. Afterwards, lightning activities ceased, and the cloud moved away from the line of sight of the radar. For an overview of the cloud, including the radar images showing its motion, see Appendix A. The fourth cloud polarimetric and Doppler radar variables are presented as functions of height and time in Figs. 19 and 20.

Figure 19(a) Differential reflectivity, (b) specific differential phase shift, (c) slanted linear depolarisation ratio, and (d) co-polar correlation coefficient of the fourth thunderstorm cloud on 18 June 2021 from 17:14 to 17:26 UTC. Vertical black lines indicate time instants at 17:20:26, 17:21:31, 17:22:25, 17:22:57, and 17:23:47 UTC.

Figure 20(a) Vertical air velocity and (b) Doppler spectrum width of the fourth thunderstorm cloud on 18 June 2021 from 17:14 to 17:26 UTC. Vertical black lines indicate time instants at 17:20:26, 17:21:31, 17:22:25, 17:22:57, and 17:23:47 UTC.

5.2.1 Alignment of particles

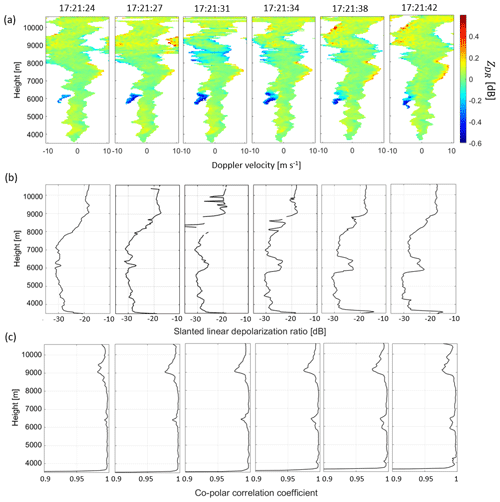

At 17:21:32 UTC, a lightning strike of 5 kA occurred around 8500 m away in the line of sight of the radar (strike number 7 in Fig. B4). This is a cloud-to-cloud lightning strike with medium strength. Between 1 and 2 s before that, negative sZDR values are observed for large and small particles from 8000 to 8800 m, as shown in Fig. 21a. The minimum value is around −0.40 dB on the left side of the spectrum and −0.36 dB on the right side of the spectrum. The sZDR values are predominantly negative across the entire spectrum, with an average value of −0.12 dB. An analysis of the spectrum at 8018 m, in comparison with the simulations presented in Fig. 10, indicates that sZDR aligns with the behaviour expected for slightly oblate particles with a canting angle of β=90°. Specifically, negative values are observed on the right side of the measured spectrum, increasing with particle size before decreasing toward the left side and coinciding with the first Mie minimum. At heights exceeding 8000 m, the spectra become broader and exhibit diminished resonance features due to enhanced turbulence. Negative sZDR values disappeared at 17:21:38 UTC, about 5 to 6 s after the lightning strike. Note that the timestamps of the cloud radar correspond to the end of the measurement after all chirp sequences have been transmitted; therefore, the spectrum at 17:21:34 UTC may contain backscattered signals before the lightning, which could explain why negative sZDR is still observed. Since the location and time of negative sZDR agree well with that of the lightning strike, and there are no other strikes close to this one in time and space, what is observed here is likely the vertical alignment and relaxation of particles right before and after a lightning strike.

Figure 21(a) Spectral differential reflectivity, (b) slanted linear depolarisation ratio, and (c) co-polar correlation coefficient before and after the lightning strike (5 kA) at 17:21:32 UTC on the line of sight of the radar between 8000 and 9000 m (strike number 7 in Fig. B4).

The SLDR across this lightning strike also shows an interesting signature. As shown in Fig. 21b, at 17:21:31 UTC, SLDR from 8000 to 8800 m suddenly decreases significantly and only recovered at 17:21:38 UTC. During this period, ρhv does not change significantly and is high (Fig. 21c). One possible cause is that almost all crystals are vertically aligned right before the lightning close to the location of lightning, which leads to low canting variance. As a result, there is a sudden decrease in SLDR.

Figure 22Spectral differential reflectivity before and after a strong lightning strike (−18 kA) at 17:20:27 UTC at 5 km cross-range (strike number 92 in Fig. B5).

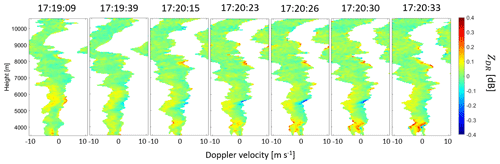

At 17:20:27 UTC, a strong cloud-to-cloud lightning discharge with a peak current of −18 kA occurred at a perpendicular distance of the range 3000 m (strike number 92 in Fig. B5), placing it at a distance of around 5500 m from the radar's line of sight. Despite being quite distant from the line of sight of the radar, negative sZDR values are observed for small particles from 5200 to 5700 m about 4 to 5 s before the lightning, as shown in Fig. 22, which is probably due to the large magnitude of the electric field that generated the strong lightning. The minimum sZDR observed is around −0.36 dB, which is similar to that observed in the previous case. Also similar to the previous case is that sZDR values returned to the level before the lightning about 4 to 5 s after the lightning from 17:20:32 UTC onward. However, unlike the previous case, negative sZDR is only found for small particles, which may be because the electric field strength reduces with distance from the lightning strike; thus, it is not strong enough to align larger and heavier particles vertically. It is difficult to pinpoint when negative sZDR first emerged due to this particular lightning strike. Slightly negative sZDR of about −0.16 dB can be found for light particles as early as 17:19:39 UTC, which could be due to a different lightning strike in the same cloud.

Also, unlike the previous case, right before the lightning at 17:20:27 UTC, SLDR does not show a sudden decrease. This could be because the lightning occurred some distance away from the line of sight of the radar. Therefore, not all particles are aligned; thus, SLDR did not decrease significantly.

In summary, the cloud-to-cloud lightning discharge within the radar's line of sight resulted in the vertical alignment of all ice particles within the radar resolution volume, whereas a discharge occurring cross-range led to the vertical alignment of only small ice particles. It should be noted that this effect may be influenced by the peak current magnitude of the lightning discharge. The vertical alignment of ice particles was observed 2 to 5 s prior to the lightning strike and dissipated 5 to 6 s afterward. These temporal estimates account for the measurement timing of chirp 3.

From 17:23:40 UTC, sZDR becomes negative for the entire Doppler spectra above 7000 m, such as the spectrum at 17:23:47 UTC shown in Fig. 26b. This could be due to the vertical alignment of all particles by strong cloud electric field. However, from Fig. 2, most of the thunderstorm cloud above 4000 m from 17:24 to 17:29 UTC was not visible to the radar due to large attenuation. There is also a significant amount of liquid water below the cloud, leading to the differential attenuation of horizontal and vertical polarisations, which may cause ZDR values to be negatively biased. Evidence of differential attenuation is that ZDR values become more negative as the thickness of the layer that contains liquid water with oblate particles increases. Also, many lightning strikes occurred close to each other in time during this period, so it is impossible to isolate each lightning strike and analyse the changes before and after each strike. These limit the investigation to the period with the most intense lightning activities.

5.2.2 Interesting microphysical properties

Evidence of conical graupel

According to Fig. 19a, from around 17:22 UTC, a region with negative differential reflectivity appears at around 4000 to 6000 m. From Fig. 19c and d, this region has an enhanced slanted linear depolarisation ratio and a reduced co-polar correlation coefficient. In fact, the SNR from 17:22 to 17:24 UTC at 4000 to 6000 m ranges from 14.0 to 40.8 dB, with a mean of 31.1 dB, suggesting that the enhanced slanted linear depolarisation ratio and reduced co-polar correlation values are not due to low SNR. Inspecting the spectrograms during this period, it is found that from 17:21:24 UTC, a separate particle mode with negative sZDR is present on the left side of the Doppler spectrum at around 6000 m, as shown in Fig. 21a. The reflectivity of this mode grew with time, and it descended to around 4300 m near 17:24 UTC. The spectral reflectivity and sZDR at a specific moment when this mode is present are shown in Fig. 23a and b. When negative sZDR appears in the left part of the spectrum, the sZDR in the right part of the spectrum is close to zero. The observed negative sZDR values in the left part of the spectrum may suggest the presence of conical graupel (Lu et al., 2016), as smaller particles, which are typically more easily aligned by an electric field, do not appear to be aligned in this case, as indicated by the absence of slightly negative sZDR values.

Figure 23Spectrograms of the (a) equivalent reflectivity and (b) differential reflectivity and profiles of the (c) slanted linear depolarisation ratio and (d) co-polar correlation coefficient at 17:22:25 UTC. Note that the x axis in panels (a) and (b) represents the vertical velocity. Spectra at 5021 m indicated by horizontal black line in panels (a) and (b) are shown in Fig. 24g–i.

Figure 24Simulated reflectivity, differential reflectivity, and differential backscatter phase of conical graupel by Lu et al. (2016) (a–c) and the T-matrix method (d–f). (g–i) Spectral reflectivity, differential reflectivity, and differential phase shift at 5021 m at 17:22:25 UTC. Note that the Doppler velocity decreases towards more negative values when the radius increases.

Figure 24g–i presents the Doppler spectra of reflectivity, ZDR, and ΨDP at 5021 m for the time instant depicted in Fig. 23. The spectral differential phase shift deviates from the Rayleigh plateau, where sΨDP(v) remains constant for velocities larger than −2 m s−1, indicating the presence of non-Rayleigh scattering. To ensure the correct interpretation of sZDR, scattering simulations are carried out using typical parameters of conical graupel. From the literature, the theoretical axis ratio of the conical graupel is 1.05, while measurements of the mean axis ratios of conical graupel show values ranging from 1.1 to 1.3 for sizes in excess of 1 mm (Spek et al., 2008). The density of the conical graupel is 0.55 g cm−3 (Spek et al., 2008), which is equivalent to an ice fraction of 0.6, while the diameter is typically 2 to 8 mm (Pruppacher and Klett, 1980). The canting angle follows a Gaussian distribution with a zero mean and a standard deviation of 0.1°. The conical shape is not supported by the simulation code used; thus, the shape is assumed to be spheroidal. Since the T-matrix method can only simulate spheroidal but not conical particles, the simulation results are also compared to the results from the database created by Lu et al. (2016) for conical graupel with a density of 0.55 g cm−3 and cone angles of 40 and 50°. The cone angles were selected to match the trend of the observations. The reflectivity, ZDR, and δco obtained from the database are shown in Fig. 24a–c, while those obtained from the T-matrix simulations are shown in Fig. 24d–f.

The trends of the differential reflectivity and differential backscatter phase obtained from the database are similar to those obtained by the T-matrix method. They are shown in Fig. 24b and e for ZDR and in Fig. 24c and f for δco. In the Rayleigh scattering regime, the differential reflectivity of the simulated conical graupel is mostly negative. ZDR and δco decrease when the Mie scattering regime is reached. δco reaches a minimum at smaller sizes than ZDR. As the particle size increases further, δco increases sharply and becomes positive, during which ZDR reaches its minimum. Afterwards, in Fig. 24f, δco reaches a local maximum and then decreases slightly, while ZDR increases in Fig. 24e. Similar patterns are evident in the Doppler spectra observed at 5021 m at 17:22:25 UTC (Fig. 24h–i). Since the constant spectral differential propagation phase (sΦDP) is nearly 0°(Doppler velocities from 2 to −1 ms−1 in Fig. 24i), the spectral differential phase shift (sΨDP) corresponds to the spectral differential backscatter phase sδco. sΨDP reaches a minimum at −3.9 m s−1 and increases sharply as the particle size further increases. sZDR reaches a minimum at −5.0 m s−1, while sΨDP is still increasing. Afterwards, sΨDP reaches a maximum and decreases slightly, while sZDR continues to increase. To summarise, the measurements of sZDR and sΨDP exhibit similar characteristics to both simulations, with sΨDP displaying a trough at smaller graupel sizes compared to sZDR.

The results derived from the database of Lu et al. (2016), the T-matrix method, and cloud radar measurements reveal similar trends; however, differences are observed in the magnitudes of ZDR and δco. Specifically, the Mie minima of ZDR and δco exhibit significantly lower values when computed using the database of Lu et al. (2016). Based on the similarity of the shapes of the curves, it is likely that the particles observed have a shape between prolate spheroids simulated by the T-matrix method and conical graupel modelled by Lu et al. (2016) with a cone angle of about 40–50°. It is also worth noting that the minimum of reflectivity in Fig. 24g is not located at the Mie minimum according to the simulation (Fig. 24d). Also, the sZDR values on the small particles side are slightly positive. This suggests that the two peaks in the spectral reflectivity represent two particle populations, with the left peak corresponding to conical graupel and with the right peak relating to nearly spherical smaller ice particles. This hypothesis is supported by a lower co-polar correlation coefficient. Furthermore, the location of the measured first Mie minimum is influenced by both the equal-volume-sphere radius and air velocity. However, a comparison of polarimetric spectra related to the same radar resolution volume reveals variations in the Mie minimum location, indicating an additional dependence on particle shape. Consequently, a simultaneous consideration of the three parameters – sZhh, sZDR, and sΨDP – at the same time and height is essential for a comprehensive analysis.

From 4400 to 5600 m, where the negative sZDR signature of graupel is the most prominent, SLDR increases and ρhv decreases, as shown in Fig. 23c and d. This is likely because the radar resolution volume contains a variety of hydrometeors, including conical graupel and other small ice particles.

Unfortunately, it is challenging to look for supercooled liquid water in this case since there is liquid water at the bottom of the cloud below the 0 °C level at around 4000 m, which means that it is impossible to identify supercooled liquid water using liquid water path. The presence of liquid water introduces an additional challenge, namely differential attenuation, which influences the sZDR values. While no direct measurements of the raindrop size distribution (RDSD) are available, a simulation can provide an estimate of the differential attenuation. For this purpose, the convective RDSD typical of the Netherlands, based on disdrometer data from Gatidis et al. (2024), is considered. The corresponding intercept parameter Nw equals 1300 mm−1 m−3, and the mass-weighted mean diameter Dm is 2.2 mm. The shape parameter, derived using the μ–λ relationship from the same study, along with the shape–size relationship used in Unal and van den Brule (2024), is applied. Consequently, in rainfall, the differential reflectivity is estimated at 0.15 dB, and the one-way differential attenuation is at 0.06 dB km−1. Except near the edges of the precipitation, ZDR measurements show an increase from 0 to 0.2 dB as the height decreases from 3000 to 2200 m. Thus, the two-way-path-integrated differential attenuation contribution is expected to be low, at less than 0.12 dB, and does not significantly affect the interpretation of the results discussed.

It is worth noting from Fig. 23a and b that the population of graupel ends at around 4000 m height, which means the region with graupel is localised in the thunderstorm cloud. Since the radar is looking at an elevation angle of 45°, this suggests that graupel is not present closer than 5700 m from the radar. At this range, measurements cannot be obtained at lower altitudes due to the 45° elevation angle. Below 4000 m, graupel begins to melt.

In Fig. 23a and b, the spectrograms are plotted with a vertical velocity instead of Doppler velocity as in other spectrograms in this article. The vertical velocity is estimated by assuming uniform horizontal wind predicted by the ECMWF model in the same hour. By plotting with vertical velocity, it is clear that the graupel are falling, while smaller ice particles on the right with positive vertical velocities are brought upwards by updrafts. As the falling graupel collide with the rising ice particles, charges can be produced. According to Takahashi (1978), if the temperature is below −10 °C, then graupel will become negatively charged, and vice versa. From the temperature profile measured by the microwave radiometer coupled to the cloud radar, the temperature is −10 °C at around 5550 m. This means that above 5550 m, falling graupel that collides with rising ice particles becomes negatively charged, forming a negative charge region in the cloud. Meanwhile, small ice particles that gained positive charges due to collisions are brought upwards by updrafts, so the upper part of the cloud is positively charged. Below 5550 m, where temperature is above −10 °C, falling graupel acquires a positive charge, causing the cloud base to become positively charged. This could result in the typical tripolar structure of thunderstorm clouds. Nonetheless, the temperature profile inside the thunderstorm cloud may be different from the temperature profile measured by the microwave radiometer looking towards the zenith, so the actual charge distribution in the cloud may be different.

Strong updraft and turbulence

As shown in Fig. 20a, from 17:18 to 17:24 UTC, the vertical air velocity is large and positive (15–30 m s−1) above 7000 m, indicating a strong updraft in the cloud. From Fig. 20b, the top of the cloud above 6000 m has a large Doppler spectrum width of 3 to 4 m s−1. In stratiform rain, the cloud top usually has low spectrum width since small and light particles have a small range of fall velocities. The large spectrum width observed here might be due to strong turbulence in the thunderstorm cloud. The slanted linear depolarisation ratio is high, and co-polar correlation coefficient is low in this region, which could be the result of large canting variance of particles due to strong turbulence.

Figure 25On 18 June 2021 at 17:22:57 UTC, where the lowest peak of SLDR and trough of ρhv is observed. (a–b) Spectrograms of reflectivity and differential reflectivity. (c–e) Spectra of reflectivity, ZDR, and ΨDP at 5060 m. (f–i) Profiles of SLDR, ρhv, vertical air velocity, and Doppler spectrum width.

From 17:22:30 to 17:24:00 UTC between 5000 and 7000 m, there are three pairs of one SLDR peak and one ρhv trough each located at the same heights. The lowest peak at around 5000 m is located just above the graupel layer, such as in the example shown in Fig. 25, where the peak is found at 5060 m. From Fig. 25h, the vertical air velocity does not vary much near this height, so the sudden increase in SLDR and decrease in ρhv may not be due to increased canting variance due to turbulence. Meanwhile, the spectral ZDR, where the peak of SLDR and ρhv is located, shows multiple peaks (Fig. 25d). This could be due to a variety of hydrometeors with different axis ratios that are the seeds for forming conical graupel. Therefore, the high SLDR and low ρhv in this case are likely due to co-existence of different types of particles.

Figure 26On 18 June 2021 at 17:23:47 UTC, where the three peaks of SLDR and troughs of ρhv are observed. (a–b) Spectrograms of reflectivity and differential reflectivity. (c–e) Spectra of reflectivity, ZDR. and ΨDP at 5877 m (middle peak) and 6422 m (highest peak). (f–i) Profiles of SLDR, ρhv, vertical air velocity, and Doppler spectrum width.

The middle and highest peaks of SLDR and troughs of ρhv are found at around 5900 m and 6400 m, such as in the example shown in Fig. 26. From Fig. 26h, vertical air velocity changes sharply at these heights, which can produce strong turbulence. Therefore, the sudden increase in SLDR and decrease in ρhv may be due to increased canting variance under turbulence. With strong turbulence, the Doppler spectra is no longer ordered with small particles on the right and large particles on the left because particles with different sizes are mixed.

Possibility of chains