the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

An improved method for atmospheric 14CO measurements

Vasilii V. Petrenko

Andrew M. Smith

Edward M. Crosier

Roxana Kazemi

Philip Place

Aidan Colton

Bin Yang

Quan Hua

Lee T. Murray

Important uncertainties remain in our understanding of the spatial and temporal variability of atmospheric hydroxyl radical concentration ([OH]). Carbon-14-containing carbon monoxide (14CO) is a useful tracer that can help in the characterization of [OH] variability. Prior measurements of atmospheric 14CO concentration ([14CO] are limited in both their spatial and temporal extent, partly due to the very large air sample volumes that have been required for measurements (500–1000 L at standard temperature and pressure, L STP) and the difficulty and expense associated with the collection, shipment, and processing of such samples. Here we present a new method that reduces the air sample volume requirement to ≈90 L STP while allowing for [14CO] measurement uncertainties that are on par with or better than prior work (≈3 % or better, 1σ). The method also for the first time includes accurate characterization of the overall procedural [14CO] blank associated with individual samples, which is a key improvement over prior atmospheric 14CO work. The method was used to make measurements of [14CO] at the NOAA Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, USA, between November 2017 and November 2018. The measurements show the expected [14CO] seasonal cycle (lowest in summer) and are in good agreement with prior [14CO] results from another low-latitude site in the Northern Hemisphere. The lowest overall [14CO] uncertainties (2.1 %, 1σ) are achieved for samples that are directly accompanied by procedural blanks and whose mass is increased to ≈50 µgC (micrograms of carbon) prior to the 14C measurement via dilution with a high-CO 14C-depleted gas.

- Article

(750 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(351 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

1.1 The importance of improving the understanding of OH variability

Atmospheric hydroxyl radical concentration ([OH]) is arguably the single most important parameter in characterizing the overall chemical state of the atmosphere, because OH serves as the main atmospheric oxidant. Reaction with OH removes a large number of atmospheric trace species, including reactive greenhouse gases like methane as well as most anthropogenic pollutants (e.g., Brasseur et al., 1999). Changes in [OH] in space and time impact both global air quality and the rate of climate change. While our understanding of and ability to predict global OH abundance and variability continues to improve, large uncertainties remain. This was highlighted, for example, by the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Modeling Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP), where individual models disagreed by ±50 % in their calculations of global mean [OH] (Naik et al., 2013; Voulgarakis et al., 2013).

OH is a very short-lived (lifetimes of 1 s or less are typical) and heterogeneously distributed species (e.g., Spivakovsky et al., 2000), making measurements inherently challenging. Therefore, characterizing global mean [OH] via direct measurements is not feasible. Instead, a number of tracers have been used for this purpose, including 14CO (e.g., Brenninkmeijer et al., 1992), methane (CH4; Montzka et al., 2011), methyl chloroform (MCF; CH3CCl3; e.g., Montzka, et al., 2011; Prinn et al., 2001), and a combination of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) (Liang et al., 2017). The approach involves selecting a trace gas with a well-characterized source and with OH as the dominant sink.

Over the last ≈2 decades, the most reliable characterization of global mean [OH] has been derived from MCF (e.g., Montzka, et al., 2011; Prinn, et al., 2001). However, MCF atmospheric mixing ratios have been declining rapidly as a result of the phase out of its production. This makes the continued use of MCF for studies of [OH] challenging, as MCF mixing ratios approach analytical detection limits and as estimates of [OH] become increasingly sensitive to poorly characterized residual MCF emissions (e.g., Rigby et al., 2017). Furthermore, while the moderately long lifetime of MCF (≈5 years; Rigby et al., 2013) has allowed for constraints on global and hemispheric mean [OH], less is known about [OH] temporal and spatial variability, which is critical for understanding the evolution, transport, and fate of air pollutants.

1.2 14CO as a tracer for atmospheric OH

Evidence from measurements of carbon-14 of atmospheric carbon monoxide (14CO) provided the first indication that carbon monoxide had a relatively short atmospheric lifetime, leading to the suggestion that tropospheric OH may be important in the removal of CO (Weinstock, 1969). Since then, measurements of 14CO concentration ([14CO]) have been used by several research groups to improve understanding of tropospheric [OH] (e.g., Brenninkmeijer, et al., 1992; Jöckel and Brenninkmeijer, 2002; Manning et al., 2005; Quay et al., 2000; Volz et al., 1981).

14CO has a strong, reliable, and well-characterized primary source (Kovaltsov et al., 2012; Poluianov et al., 2016). This is an advantage over CO, CH4, or halocarbon tracers for OH, which typically have variable emissions that are associated with relatively large uncertainties. 14C is produced from 14N via interactions with neutrons (14N(n,p)14C) resulting from bombardment of the atmosphere by galactic cosmic rays. Production rates are highest in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere (UT/LS), with about half of 14C produced in each region. The geomagnetic field provides the strongest cosmic ray shielding in the low latitudes, resulting in higher 14C production rates in the middle and high latitudes (e.g., Masarik and Beer, 1999). Variations in the 14C production rate are well characterized from neutron monitor observations (e.g., Kovaltsov et al., 2012; Usoskin et al., 2011). Once produced, 14C quickly reacts to form 14CO, with ≈93 %–95 % yield (Mak et al., 1994; Jockel and Brenninkmeijer, 2002).

The dominant 14CO removal mechanism is via reaction with OH; 14CO can therefore in principle serve as a tracer for OH abundance and variability. There are several aspects of atmospheric cycling of 14CO that offer either challenges or advantages in its use as a tracer for [OH], depending on the question being posed. First, 14CO (and CO) has a relatively short average tropospheric lifetime of ≈2 months, which varies by latitude (shortest in the tropics) and by season (shortest in season of maximum insolation), following variations in [OH] (e.g., Spivakovsky, et al., 2000). This is much shorter than the interhemispheric mixing time of ≈1 year, and it means that [14CO] measurements at a given station are sensitive to regional rather than global [OH] (Krol et al., 2008), presenting a challenge for using [14CO] to constrain global mean [OH] abundance and variability. To ensure robust characterization of global mean [OH] from [14CO] alone, records for multiple sampling stations are necessary.

The limited spatial footprint of [14CO] sensitivity to [OH] can instead be an advantage if the question is one of OH spatial and seasonal variability. Driven by strong seasonality and meridional gradients in [OH], cosmogenic production rates, and stratosphere-to-troposphere (STT) transport, as well as a relatively short chemical lifetime, [14CO] near the surface shows strong seasonal and meridional variability (e.g., Jöckel and Brenninkmeijer, 2002).

1.3 Atmospheric [14CO] measurement techniques and associated challenges

14CO is an ultra-trace constituent of the atmosphere, with surface concentrations ranging between ≈4 and 25 molecules cm−3 STP. This has necessitated very large sample volumes of 500–1000 L STP for the analyses (e.g., Brenninkmeijer, 1993; Mak et al., 1994). Air samples are typically collected into high-pressure aluminum cylinders with the use of modified three-stage oil-free compressors (e.g., Mak and Brenninkmeijer, 1994). The collected air is processed by first removing condensable gases using high-efficiency cryogenic traps (Brenninkmeijer, 1991), followed by oxidation of CO to CO2 using the Schutze reagent and subsequent cryogenic trapping of the CO-derived CO2 using liquid nitrogen (Brenninkmeijer, 1993). The produced CO2 is then graphitized and analyzed for 14C using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) (Brenninkmeijer, 1993).

There are two main challenges associated with atmospheric 14CO measurements. First, the very large air sample volumes and the need for high-pressure gas cylinders result in relatively complex and expensive logistics and sample processing. These challenges have limited the extent of 14CO atmospheric measurements collected to date. Second, 14CO production by cosmic rays via the 14N(n,p)14C mechanism continues in air sample containers after the samples have been collected (the “in situ component”; e.g., Lowe et al., 2002; Mak et al., 1999). This effect is particularly large for samples stored at high altitudes and high latitudes, as well as for samples transported by air, and has contributed significantly to uncertainties in interpretation of [14CO] measurements (e.g., Jöckel and Brenninkmeijer, 2002).

In this paper, we describe a new method for atmospheric [14CO] measurements that addresses both of the above challenges, demonstrate the use of this method, and discuss how measurement uncertainties can be minimized in this approach.

2.1 Atmospheric sample collection system and procedure

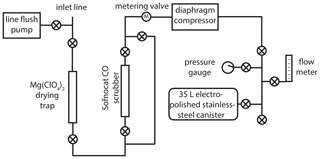

The new atmospheric sampling system (Fig. 1) was developed and installed at the NOAA Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO; 19.5∘ N, 155.6∘ W; 3397 m above sea level) in November 2017. A in. o.d. inlet line (Synflex 1300) was mounted near the top of a ≈36 m tower. A small diaphragm pump (Air Cadet EW-07532-40) continuously flushes the inlet line at a flow rate of ≈5 L min−1 when not sampling. The main part of the sampling system consists of a drying trap (45 g of anhydrous Mg(ClO4)2 in a 1 in. o.d. steel tube), a CO removal trap (25 g of Sofnocat 423 from Molecular Products in a in. o.d. steel tube), a diaphragm compressor (KNF N145 with neoprene diaphragms), and a pre-evacuated (to 0.25 Torr) lightweight electropolished stainless-steel canister (Essex Cryogenics, 35 L internal volume).

Figure 1Schematic of the new atmospheric 14CO sampling system deployed at the Mauna Loa Observatory. A “⊗” symbol within a circle denotes a valve (Swagelok, 4H bellows-sealed).

Prior to collecting an air sample, the diaphragm compressor is leak checked using the pressure gauge. The air flow is then directed into the main part of the system and bypasses the Sofnocat CO scrubber; the flow is adjusted to ≈5 L min−1 using the metering valve. The system is flushed for 4 min; then the connection to the sample canister is pressure-flushed (to ≈172 000 Pa above ambient pressure) three times. The sample canister is initially opened slowly, keeping the pressure upstream of the canister slightly above ambient (to minimize the impact of any leaks and help maintain a relatively constant flow rate); then it is opened fully once pressure in the canister reaches ambient.

In an attempt to provide some temporal averaging for 14CO samples at MLO, most sample canisters were filled in two separate sessions ≈1 week apart, with half the air volume collected each time. A few of the canisters (Table S1 in the Supplement) were filled in a single session, when atmospheric conditions at MLO did not allow for sampling during one of the targeted weeks (e.g., during volcanic plumes). The final air volumes in the canisters were ≈90 L STP, allowing for nonhazardous shipping. The system also allows for air collection in blank mode, where the flow is directed through the Sofnocat CO scrubber. This removes all 14CO (and CO), allowing us to assess the cumulative procedural addition of extraneous 14CO to the samples, including in situ 14CO production by cosmic rays inside the canisters during transport and storage. Samples were collected between November 2017 and November 2018. Every 2 weeks, two canisters were filled: either two samples or a sample and a blank (Tables S1 and S2). Once complete, sample and blank canisters were moved down to sea level on the same day to minimize in situ 14CO production (which increases approximately exponentially with altitude in the troposphere) and shipped via air to the University of Rochester within 1–2 d.

2.2 Sample air processing and measurements

Sample air processing and measurement approaches at University of Rochester are based on methods developed earlier for 14CO analyses in samples of air extracted from glacial firn and ice (Dyonisius et al., 2020; Hmiel et al., 2020; Petrenko et al., 2016, 2017). Here we provide a brief description, including changes and details specific to the MLO 14CO samples. The air samples are first measured for CO mole fraction ([CO]) against NOAA-calibrated standards using a Picarro G2401 cavity ring-down spectroscopic analyzer; this measurement consumes ≈800 cm3 STP. A high-[CO] gas (10.02±0.06 µmol mol−1; from Praxair, Inc.) containing 14C-depleted CO is then added to the sample canisters; this step will henceforth be referred to as the “dilution”. The dilution simultaneously serves to increase the carbon mass in the sample to a level that is necessary for robust measurement by AMS and reduce the 14C activity of the samples to values that are within the range of common 14C measurement standards.

The relative proportions of sample air and the high-[CO] dilutant gas are determined using a Paroscientific 745-100A pressure transducer (0.01 % absolute accuracy) while monitoring the canister temperatures. For the first of the samples, the dilutions were designed to produce a final sample size of ≈22 µgC (micrograms of carbon). For the final of the samples, the amount of the dilutant gas was increased to produce final sample sizes of ≈50 µgC, to investigate whether the somewhat larger sample sizes would yield smaller overall uncertainties.

The diluted air samples were processed using a system previously developed at University of Rochester (Dyonisius, et al., 2020; Hmiel, et al., 2020). Briefly, the sample air stream (at 1 L min−1 STP) first passes through a coaxial Pyrex trap held at −75 ∘C, followed by four Pyrex traps containing nested fiberglass thimbles (“Russian Doll” traps; Brenninkmeijer, 1991) held at −196 ∘C with liquid nitrogen. These traps serve to remove H2O, CO2, and other condensable gases. The Russian doll traps are also very effective at removing hydrocarbons, including C2 hydrocarbons (Brenninkmeijer, 1991; Petrenko et al., 2008; Pupek et al., 2005). Following cryogenic purification, the air stream passes through a furnace containing 2 g of platinized quartz wool (Shimadzu part no. 630-00996-00) held at 175 ∘C; this oxidizes CO to CO2 while allowing CH4 to pass through unaffected. The CO-derived CO2 is then cryogenically trapped and further purified to remove trace amounts of H2O and air. The amount of collected CO2 is then quantified in a calibrated volume, and the CO2 is flame-sealed into 6 mm o.d. Pyrex tubes for storage and shipment to the AMS facility. This CO2 is converted to graphite (Yang and Smith, 2017) and subsequently measured for 14C using the 10 MV ANTARES accelerator facility at ANSTO (Smith et al., 2010). The MLO samples and blanks were processed at ANSTO in four separate sets, and each of these sets was accompanied by commensurately sized 14C standards and blanks prepared at ANSTO, including the international 14C standards HOxII, IAEA-C7, IAEA-C8, and aliquots from a previously well-characterized cylinder of 14C-depleted CO2.

δ13C of CO in the high-[CO] 14C-depleted dilution gas (needed for 14C normalization; e.g., Stuiver and Polach, 1977) was measured as described in Dyonisius et al. (2020). δ13C of CO in the air samples was measured using a new system at the University of Rochester, following the design and procedure described in Vimont et al. (2017).

2.3 Data processing and corrections

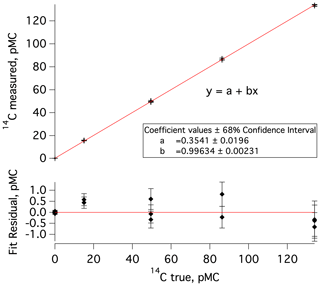

The data processing and corrections approach largely follows prior work (e.g., Dyonisius et al., 2020; Petrenko et al., 2016). Here we provide a brief summary as well as highlight differences from prior work. First, in a departure from prior work, measured 14C values (in pMC units, percent modern carbon; Stuiver and Polach, 1977) are empirically corrected for any effects of processing at ANSTO (handling of sample-derived CO2, conversion to graphite, and the AMS measurement). This is accomplished by plotting the measured 14C values of commensurately sized standards against the accepted 14C values for these standards and using the Igor Pro software to determine linear fit coefficients and associated uncertainties (Fig. 2). This correction was determined separately for each measured set of MLO samples and blanks and is small (<2 % in all cases).

Figure 2Top: a plot of measured versus true (accepted) 14C values for commensurately sized 14C standards and blanks that were processed at ANSTO concurrently with the second set of MLO 14CO samples and blanks (samples 7–18 in Table S1 and blanks 3–6 in Table S2). The data point clusters, going from left to right, represent a previously characterized cylinder of 14C-depleted CO2 (14C true =0.03 pMC), IAEA-C8 (14C true pMC; Le Clercq et al., 1998), IAEA-C7 (14C true pMC; Le Clercq et al., 1998), a second previously characterized cylinder of CO2 (14C true =86.27 pMC), and HOxII (14C true pMC; Wacker et al., 2019, and references therein). Bottom: residuals from the linear fit in the upper plot; error bars represent uncertainty in 14C measured.

[CO] in the diluted samples and blanks was calculated based on [CO] in the samples and in the high-[CO] dilution gas and the pre- and post-dilution pressures, corrected for any temperature change in the canisters in between the two pressure measurements. δ13C of CO in the diluted samples was calculated using an equivalent approach. 14CO content in the diluted samples and blanks is then calculated using

where 14C is the number of 14CO molecules cm−3 STP, pMC is the measured sample or blank 14C activity in pMC units after the empirical correction for ANSTO processing, λ is the 14C decay constant ( yr−1), y is the year of measurement, δ13C is the calculated δ13C of CO in the diluted sample or blank, 0.975 is a factor arising from 14C activity normalization to δ13C of −25 ‰ associated with pMC units, is the ) ratio corresponding to the absolute international 14C standard activity (Hippe and Lifton, 2014), 22 400 is the number of cubic centimeters of gas per mole at standard temperature and pressure, and NA is the Avogadro constant.

Next, the 14CO content in the diluted samples and blanks that is attributable to the high-[CO] 14C-depleted dilution gas is calculated, again using Eq. (1). Triplicate aliquots of dilution gas (all ≈50 µgC) were processed and measured for 14C near the start and again at the end of the 1-year sampling campaign. The 14C activity of CO in the dilution gas is expected to increase slowly with time due to in situ production in the gas cylinder. For the analysis of the first MLO sample set, the mean value obtained from the initial set of 14C measurements of the dilution gas was used (0.19±0.04 pMC, 1σ, after corrections for ANSTO processing). For the analysis of the final MLO sample set, the mean value obtained from the second set of 14C measurements of the dilution gas was used (0.46±0.10 pMC). For the analysis of the second and third MLO sample sets, the average of the two sets of 14C measurements on the dilution gas was used. For the 14CO content calculation in this case, [CO] is the CO mole fraction in the diluted samples and blanks that is attributable to the dilution gas only.

The 14CO content that is attributable to the high-[CO] 14C-depleted dilution gas is then subtracted from the total 14CO content. The 14CO content is then further corrected for the volumetric effect of the dilution, which reduces the number of 14CO molecules cm−3 STP of gas. This yields the 14CO content in undiluted samples and blanks. The final step of the data processing involves the procedural blank correction. For samples that were directly accompanied by a blank, the 14CO content of that blank is subtracted. This accounts for all extraneous 14CO affecting that particular sample. For samples that were not directly accompanied by a blank, the average 14CO content determined from all blanks collected in a similar mode (tanks filled on two separate days ≈1 week apart versus tanks filled in a single session) was subtracted.

All uncertainties were propagated through the data reduction and correction calculations using standard error propagation techniques. For one of the sample sets, the errors were also propagated using a Monte Carlo approach to confirm that this yields equivalent uncertainties.

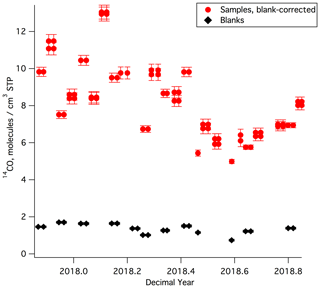

The MLO sample and blank [14CO] results are shown in Fig. 3 and listed in Tables S1 and S2. [14CO] at MLO during the year of sampling ranged from 5–13 molecules cm−3 STP. There is a clear seasonal cycle, with lowest values during the summer and highest values during the winter, as observed in prior work (e.g., Manning et al., 2005). The relatively high temporal variability in [14CO], which is particularly prominent in the winter season, is likely driven by the competing influences of low-latitude versus midlatitude air masses at MLO (the [14CO] shows a very strong meridional gradient, particularly in the winter season, with much higher values at higher latitudes; e.g., Jöckel and Brenninkmeijer, 2002). For a first-order comparison with prior [14CO] measurements, we consider Ragged Point, Barbados (13.2∘ N), which is the station with available finalized and previously published [14CO] measurements that is closest in latitude to MLO (19.5∘ N). The prior Barbados [14CO] measurements (July 1996–July 1997; Mak and Southon, 1998) showed seasonal [14CO] variability in a similar range (5–12 molecules cm−3 STP) as our new MLO data, although the Barbados measurements were not corrected for in situ 14CO production in the sample tanks, and atmospheric 14C production may have been somewhat different during 1996–1997 as compared to 2017–2018.

Figure 3[14CO] results for all MLO samples and blanks. Most samples and blanks were collected by half filling the canisters on two separate days. To illustrate this, [14CO] values for these samples and blanks are plotted for each of these dates, appearing twice as adjacent data points. All shown [14CO] uncertainties are 1σ. We observed a correlation for sample–blank pairs collected on the same day. This correlation is not due to analytical artifacts and is discussed in detail in the Supplement.

The average 1σ overall uncertainty of the measured MLO [14CO] values after corrections (obtained via uncertainty propagation) is 0.27 molecules cm−3 STP or 3.3 % of the average [14CO] value. Pooled standard deviation computed from 12 replicate sample pairs provides an estimate of repeatability and is 0.18 molecules cm−3 STP, corresponding to 2.2 % of the average 14CO value for all the replicate samples. MLO is a low-latitude site, with lower [14CO] as compared to most previously monitored sites; this means that the same absolute [14CO] uncertainty would translate into a larger relative uncertainty for MLO than for most other sites. Despite this, our results compare well with overall 1σ uncertainties reported in prior work that used much larger samples at sites with higher [14CO] (4 % for Quay et al., 2000, and 4 %–5 % for Manning et al., 2005). Brenninkmeijer (1993) and Röckmann et al. (2002) report [14CO] uncertainties of ≈2 %, but those estimates did not take into account the uncertainty associated with the correction for in situ 14CO production in sample tanks during storage and transport.

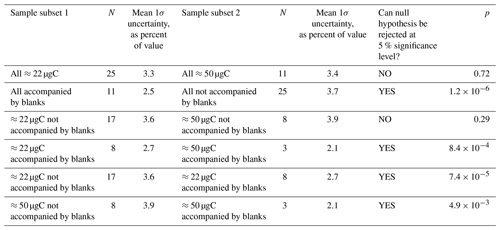

Table 1Results of a two-sample t test investigating the effects of measured sample mass, whether the sample was accompanied by a blank, or both on the final relative uncertainty in the determined sample [14CO] value. N is the number of samples in a particular subset. The null hypothesis is that the two subsets being compared are drawn from populations with equal means. The null hypothesis is rejected (i.e., the t test indicates that the means of the subsets are significantly different) if the probability (p) of the observed subsets occurring when the underlying populations have equal means is less than 0.05 (<5 %).

The overall procedural blank for the MLO 14CO samples (Fig. 3; Table S2) is relatively large (average blank [14CO] amounts to 16 % of the average corrected sample [14CO]) and variable (relative standard deviation of 21 %), highlighting the need for accurate blank characterization. This blank is not due to outgassing from system components or other analytical artifacts (see the Supplement for detailed discussion) but arises almost entirely from in situ 14CO production by cosmic rays. In situ 14CO production in the sample canisters during storage at the high-altitude MLO site in between the two separate days on which the canisters are filled and during aircraft transport from Hawaii to Rochester both appear to be important. Two of the blank canisters were filled in a single day rather than half filled on two separate days a week apart (Table S2). For these two blanks, average [14CO] is 0.95 molecules cm−3 STP, as compared to average [14CO] of 1.42 molecules cm−3 STP for the 10 blanks half filled on two separate days. In situ production in the canisters during aircraft shipment between Hawaii and Rochester thus appears to be larger than production during canister storage at MLO.

One of the main objectives with the MLO sample set was method optimization to reduce uncertainties. We used a two-sample t test to investigate the effects of sample carbon mass and whether or not a sample was directly accompanied by a procedural blank on the overall sample [14CO] uncertainties after corrections (Table 1). A procedural blank that directly accompanies a sample should in principle be affected by the same amount of in situ 14CO production, allowing for the blank 14CO content to be directly subtracted from the 14CO content of the accompanying sample. For samples that are not directly accompanied by a blank, the variability in the blanks must be considered, adding to uncertainty. As expected, the overall uncertainties are significantly lower for samples that are accompanied by blanks (Table 1). This finding is true if all samples are considered, as well as for the ≈22 and ≈50 µgC sample subsets.

Sample carbon mass (mass of graphite actually measured for 14C by AMS) may matter for two reasons. First, a larger carbon mass in principle makes the sample less susceptible to problems during graphitization and AMS measurement. Second, an analysis of the relative contributions of individual uncertainties to the final overall uncertainty revealed that the uncertainty arising from the dilution with the high-[CO] 14C-depleted gas was a key contributor. For the smaller ≈22 µgC final sample masses, a relatively small amount of the high-[CO] gas (≈4 L STP) was being added to a large amount of sample air (≈90 L STP). This resulted in a relative error of ≈2 % for the fraction of the diluted sample carbon that originated from the high-[CO] gas. Increasing the final sample carbon mass to ≈50 µgC via increasing the amount of the high-[CO] gas added during dilution reduces this relative error to <1 %. Surprisingly, we did not observe a significant reduction in the relative [14CO] uncertainty when all ≈22 µgC samples are compared to all ≈50 µgC samples (Table 1). However, there was a significant uncertainty reduction associated with larger sample mass if only the subset of samples directly accompanied by blanks was considered.

The described new atmospheric [14CO] measurement method uses much smaller sample air volumes than prior work, simplifying sample collection, processing, and field logistics and reducing costs; the new method appears to perform well. The MLO [14CO] measurements made with this method show good first-order agreement with prior measurements at a different Northern Hemisphere low-latitude site. The method allows for accurate characterization of the extraneous 14CO component from in situ cosmogenic production in sample canisters, showing that this component can be relatively large and variable. In terms of sample measurement uncertainties, the new method compares favorably with prior work that utilized 5–10 times larger air sample volumes. A significant improvement in overall measurement uncertainties is achieved for samples that are directly accompanied by procedural blanks, highlighting the usefulness of this mode of sample collection. The lowest overall [14CO] uncertainties (2.1 %, 1σ) were achieved for samples that were directly accompanied by procedural blanks and were diluted with a relatively larger amount of high-[CO] 14C-depleted gas to increase the final sample sizes for AMS analysis to ≈50 µgC.

All the new [14CO] data discussed in this article are available in the Supplement (Tables S1 and S2).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-14-2055-2021-supplement.

VVP and LTM designed the study. VVP guided all aspects of system development, sample collection, and processing; analyzed the results; and wrote the article. AMS made the 14C measurements. EMC built the air sampler. AC collected the air samples. EMC, RK, and PP processed the air samples. BY and QH graphitized the samples. All authors contributed to improving the article.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by the David and Lucille Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering (to Vasilii V. Petrenko). We acknowledge the financial support from the Australian Government for the Centre for Accelerator Science at ANSTO through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy. We thank Ed Dlugokencky, Brian Vasel, and Darryl Kuniyuki for facilitating access to sampling at MLO and Emily Mesiti for assistance with researching and ordering system components. This article was improved as a result of reviews by Martin Manning and an anonymous reviewer.

This research has been supported by the David and Lucille Packard Foundation (Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering).

This paper was edited by Huilin Chen and reviewed by Martin Manning and one anonymous referee.

Brasseur, G., Orlando, J., and Tyndall, G.: Atmospheric Chemistry and Global Change, Oxford University Press, New York, 654 pp., 1999.

Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.: Robust, High-Efficiency, High-Capacity Cryogenic Trap, Anal. Chem., 63, 1182–1184, 1991.

Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.: Measurement of the Abundance of (CO)-C-14 in the Atmosphere and the C-13 C-12 and O-18 O-16 Ratio of Atmospheric CO with Applications in New Zealand and Antarctica, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 98, 10595–10614, 1993.

Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., Manning, M. R., Lowe, D., Wallace, G., Sparks, R., and Volz-Thomas, A.: Interhemispheric asymmetry in OH abundance inferred from measurements of atmospheric 14CO, Nature, 356, 50–52, 1992.

Dyonisius, M. N., Petrenko, V. V., Smith, A. M., Hua, Q., Yang, B., Schmitt, J., Beck, J., Seth, B., Bock, M., Hmiel, B., Vimont, I., Menking, J. A., Shackleton, S. A., Baggenstos, D., Bauska, T. K., Rhodes, R. H., Sperlich, P., Beaudette, R., Harth, C., Kalk, M., Brook, E. J., Fischer, H., Severinghaus, J. P., and Weiss, R. F.: Old carbon reservoirs were not important in the deglacial methane budget, Science, 367, 907–910, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax0504, 2020.

Hippe, K. and Lifton, N. A.: Calculating Isotope Ratios and Nuclide Concentrations for in Situ Cosmogenic C-14 Analyses, Radiocarbon, 56, 1167–1174, https://doi.org/10.2458/56.17917, 2014.

Hmiel, B., Petrenko, V. V., Dyonisius, M. N., Buizert, C., Smith, A. M., Place, P. F., Harth, C., Beaudette, R., Hua, Q., Yang, B., Vimont, I., Michel, S. E., Severinghaus, J. P., Etheridge, D., Bromley, T., Schmitt, J., Fain, X., Weiss, R. F., and Dlugokencky, E.: Preindustrial 14CH4 indicates greater anthropogenic fossil CH4 emissions, Nature, 578, 409–412, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1991-8, 2020.

Jöckel, P. and Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.: The seasonal cycle of cosmogenic (14)CO at the surface level: A solar cycle adjusted, zonal-average climatology based on observations, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, 4656, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jd001104, 2002.

Kovaltsov, G. A., Mishev, A., and Usoskin, I. G.: A new model of cosmogenic production of radiocarbon 14C in the atmosphere, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 337–338, 114–120, 2012.

Krol, M. C., Meirink, J. F., Bergamaschi, P., Mak, J. E., Lowe, D., Jöckel, P., Houweling, S., and Röckmann, T.: What can 14CO measurements tell us about OH?, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 5033–5044, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-5033-2008, 2008.

Le Clercq, M., van der Plicht, J., and Gröning, M.: New 14C reference materials with activities of 15 and 50 pMC, Radiocarbon, 40, 295–297, 1998.

Liang, Q., Chipperfield, M. P., Fleming, E. L., Abraham, N. L., Braesicke, P., Burkholder, J. B., Daniel, J. S., Dhomse, S., Fraser, P. J., Hardiman, S. C., Jackman, C. H., Kinnison, D. E., Krummel, P., Montzka, S. A., Morgenstern, O., McCulloch, A., Muhle, J., Newman, P., Orkin, V. L., Pitari, G., Prinn, R., Rigby, M., Rozanov, E., Stenke, A., Tummon, F., Velders, G. J. M., Visioni, D., and Weiss, R. F.: Deriving Global OH Abundance and Atmospheric Lifetimes for Long-Lived Gases: A Search for CH3CCl3 Alternatives, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 122, 11914–11933, 2017.

Lowe, D. C., Levchenko, V. A., Moss, R. C., Allan, W., Brailsford, G. W., and Smith, A. M.: Assessment of ”storage correction” required for in situ (CO)-C-14 production in air sample cylinders, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 1139, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014719, 2002.

Mak, J. and Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.: Compressed Air Sample Technology for Isotopic Analysis of Atmospheric Carbon Monoxide, J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech., 11, 425–431, 1994.

Mak, J. E. and Southon, J. R.: Assessment of tropical OH seasonality using atmospheric (CO)-C-14 measurements from Barbados, Geophys. Res. Lett., 25, 2801–2804, https://doi.org/10.1029/98gl02180, 1998.

Mak, J., Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., and Tamaresis, J.: Atmospheric 14CO observations and their use for estimating carbon monoxide removal rates, J. Geophys. Res., 99, 22915–22922, 1994.

Mak, J., Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., and Southon, J.: Direct measurement of the production rate of 14C near the Earth's surface, Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 3381–3384, 1999.

Manning, M. R., Lowe, D. C., Moss, R. C., Bodeker, G. E., and Allan, W.: Short-term variations in the oxidizing power of the atmosphere, Nature, 436, 1001–1004, 2005.

Masarik, J. and Beer, J.: Simulation of particle fluxes and cosmogenic nuclide production in the Earth's atmosphere, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 104, 12099–12111, 1999.

Montzka, S. A., Krol, M., Dlugokencky, E., Hall, B., Jockel, P., and Lelieveld, J.: Small Interannual Variability of Global Atmospheric Hydroxyl, Science, 331, 67–69, https://doi.org/10.1126/Science.1197640, 2011.

Naik, V., Voulgarakis, A., Fiore, A. M., Horowitz, L. W., Lamarque, J.-F., Lin, M., Prather, M. J., Young, P. J., Bergmann, D., Cameron-Smith, P. J., Cionni, I., Collins, W. J., Dalsøren, S. B., Doherty, R., Eyring, V., Faluvegi, G., Folberth, G. A., Josse, B., Lee, Y. H., MacKenzie, I. A., Nagashima, T., van Noije, T. P. C., Plummer, D. A., Righi, M., Rumbold, S. T., Skeie, R., Shindell, D. T., Stevenson, D. S., Strode, S., Sudo, K., Szopa, S., and Zeng, G.: Preindustrial to present-day changes in tropospheric hydroxyl radical and methane lifetime from the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 5277–5298, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-5277-2013, 2013.

Petrenko, V. V., Smith, A. M., Brailsford, G., Riedel, K., Hua, Q., Lowe, D., Severinghaus, J. P., Levchenko, V., Bromley, T., Moss, R., Muhle, J., and Brook, E. J.: A new method for analyzing C-14 of methane in ancient air extracted from glacial ice, Radiocarbon, 50, 53–73, 2008.

Petrenko, V. V., Severinghaus, J. P., Schaefer, H., Smith, A. M., Kuhl, T., Baggenstos, D., Hua, Q., Brook, E. J., Rose, P., Kulin, R., Bauska, T., Harth, C., Buizert, C., Orsi, A., Emanuele, G., Lee, J. E., Brailsford, G., Keeling, R., and Weiss, R. F.: Measurements of C-14 in ancient ice from Taylor Glacier, Antarctica constrain in situ cosmogenic (CH4)-C-14 and (CO)-C-14 production rates, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 177, 62–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.01.004, 2016.

Petrenko, V. V., Smith, A. M. S., Schaefer, H. S., Riedel, K., Brook, E., Baggenstos, D., Harth, C., Hua, Q., Buizert, C., Schilt, A., Fain, X., Mitchell, L., Bauska, T., Orsi, A., Weiss, R. F., and Everinghaus, J. P. S.: Minimal geological methane emissions during the Younger Dryas-Preboreal abrupt warming event, Nature, 548, 443–446, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23316, 2017.

Poluianov, S. V., Kovaltsov, G. A., Mishev, A. L., and Usoskin, I. G.: Production of cosmogenic isotopes 7Be, 10Be, 14C, 22Na, and 36Cl in the atmosphere: Altitudinal profiles of yield functions, J. Geophys. Res., 121, 8125–8136, 2016.

Prinn, R. G., Huang, J., Weiss, R. F., Cunnold, D. M., Fraser, P. J., Simmonds, P. G., McCulloch, A., Harth, C., Salameh, P., O'Doherty, S., Wang, R. H. J., Porter, L., and Miller, B. R.: Evidence for substantial variations of atmospheric hydroxyl radicals in the past two decades, Science, 292, 1882–1888, 2001.

Pupek, M., Assonov, S. S., Muhle, J., Rhee, T. S., Oram, D., Koeppel, C., Slemr, F., and Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.: Isotope analysis of hydrocarbons: trapping, recovering and archiving hydrocarbons and halocarbons separated from ambient air, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 19, 455–460, 2005.

Quay, P., King, S., White, D., Brockington, M., Plotkin, B., Gammon, R., Gerst, S., and Stutsman, J.: Atmospheric 14CO: A tracer of OH concentration and mixing rates, J. Geophys. Res., 105, 15147–15166, 2000.

Rigby, M., Prinn, R. G., O'Doherty, S., Montzka, S. A., McCulloch, A., Harth, C. M., Mühle, J., Salameh, P. K., Weiss, R. F., Young, D., Simmonds, P. G., Hall, B. D., Dutton, G. S., Nance, D., Mondeel, D. J., Elkins, J. W., Krummel, P. B., Steele, L. P., and Fraser, P. J.: Re-evaluation of the lifetimes of the major CFCs and CH3CCl3 using atmospheric trends, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 2691–2702, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-2691-2013, 2013.

Rigby, M., Montzka, S. A., Prinn, R., White, J. W. C., Young, D., O'Doherty, S., Lunt, M. F., Ganesan, A. L., Manning, A. J., Simmonds, P., Salameh, P., Harth, C., Muhle, J., Weiss, R., Fraser, P., Steele, L. P., Krummel, P., McCulloch, A., and Park, S.: Role of atmospheric oxidation in recent methane growth, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, 5373–5377, 2017.

Röckmann, T., Jöckel, P., Gros, V., Bräunlich, M., Possnert, G., and Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.: Using 14C, 13C, 18O and 17O isotopic variations to provide insights into the high northern latitude surface CO inventory, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 2, 147–159, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2-147-2002, 2002.

Smith, A. M., Hua, Q., Williams, A., Levchenko, V., and Yang, B.: Developments in micro-sample C-14 AMS at the ANTARES AMS facility, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B, 268, 919–923, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2009.10.064, 2010.

Spivakovsky, C. M., Logan, J. A., Montzka, S. A., Balkanski, Y. J., Foreman-Fowler, M., Jones, D. B. A., Horowitz, L. W., Fusco, A. C., Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M., Prather, M. J., Wofsy, S. C., and McElroy, M. B.: Three-dimensional climatological distribution of tropospheric OH: Update and evaluation, J. Geophys. Res., 105, 8931–8980, 2000.

Stuiver, M. and Polach, H. A.: Reporting of C-14 Data - Discussion, Radiocarbon, 19, 355–363, 1977.

Usoskin, I. G., Bazilevskaya, G. A., and Kovaltsov, G. A.: Solar modulation parameter for cosmic rays since 1936 reconstructed from ground-based neutron monitors and ionization chambers, J. Geophys. Res., 116, A02104, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JA016105, 2011.

Vimont, I. J., Turnbull, J. C., Petrenko, V. V., Place, P. F., Karion, A., Miles, N. L., Richardson, S. J., Gurney, K., Patarasuk, R., Sweeney, C., Vaughn, B., and White, J. W. C.: Carbon monoxide isotopic measurements in Indianapolis constrain urban source isotopic signatures and support mobile fossil fuel emissions as the dominant wintertime CO source, Elementa, 5, 63, https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.136, 2017.

Volz, A., Ehhalt, D. H., and Derwent, R. G.: Seasonal and Latitudinal Variation of 14CO and the Tropospheric Concentration of OH Radicals, J. Geophys. Res., 86, 5163–5171, 1981.

Voulgarakis, A., Naik, V., Lamarque, J.-F., Shindell, D. T., Young, P. J., Prather, M. J., Wild, O., Field, R. D., Bergmann, D., Cameron-Smith, P., Cionni, I., Collins, W. J., Dalsøren, S. B., Doherty, R. M., Eyring, V., Faluvegi, G., Folberth, G. A., Horowitz, L. W., Josse, B., MacKenzie, I. A., Nagashima, T., Plummer, D. A., Righi, M., Rumbold, S. T., Stevenson, D. S., Strode, S. A., Sudo, K., Szopa, S., and Zeng, G.: Analysis of present day and future OH and methane lifetime in the ACCMIP simulations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 2563–2587, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-2563-2013, 2013.

Wacker, L., Bollhalder, S. Sookdeo, A., and Synal, H.A.: Re-valuation of the new oxalic acid standard with AMS, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B, 455, 178–180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2018.12.035, 2019.

Weinstock, B.: Carbon Monoxide – Residence Time in Atmosphere, Science, 166, 224–225, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.166.3902.224, 1969.

Yang, B. and Smith, A. M.: Conventionally Heated Microfurnace for the Graphitization of Microgram-Sized Carbon Samples, Radiocarbon, 59, 859–873, https://doi.org/10.1017/Rdc.2016.89, 2017.