the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Aerosol trace element solubility determined using ultrapure water batch leaching: an intercomparison study of four different leaching protocols

Rui Li

Prema Piyusha Panda

Yizhu Chen

Zhenming Zhu

Fu Wang

Yujiao Zhu

He Meng

Yan Ren

Ashwini Kumar

Solubility of aerosol trace elements, which determines their bioavailability and reactivity, is operationally defined and strongly depends on the leaching protocol used. Ultrapure water batch leaching is one of the most widely used leaching protocols, while the specific leaching protocols used in different labs can still differ in agitation methods, contact time, and filter pore size. It is yet unclear to which extent the difference in these experimental parameters would affect the aerosol trace element solubility reported. This work examined the effects of agitation methods, filter pore size, and contact time on the solubility of nine aerosol trace elements and found that the difference in agitation methods (shaking vs. sonication), filter pore size (0.22 vs. 0.45 µm), and contact time (1 vs. 2 h) only led to small and sometimes insignificant difference in the reported solubility. We further compared aerosol trace element solubility determined using four ultrapure water leaching protocols, which are adopted by four different labs and vary in agitation methods, filter pore size, and/or contact time, and observed good agreement in the reported solubility. Therefore, our work suggests that although ultrapure water batch leaching protocols used by different labs vary in specific experimental parameters, the determined aerosol trace element solubility is comparable. We recommend that ultrapure water batch leaching be one of the reference leaching schemes and emphasize that additional consensus in the community on agitation methods, contact time, and filter pore size is needed to formulate a standard operating procedure for ultrapure water batch leaching.

- Article

(872 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2334 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Aerosol trace elements, originating from natural and anthropogenic sources, are of great concern as they significantly impact marine and terrestrial ecosystems (Boyd and Ellwood, 2010; Dong et al., 2023; Mahowald et al., 2018), have adverse effects on human health (Dahmardeh Behrooz et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2019), and play important roles in atmospheric chemistry (Al-Abadleh, 2024; Alexander et al., 2009; Mao et al., 2013; Martin and Hill, 1987; Wang et al., 2021). The dissolved fraction of aerosol trace elements, instead of their total abundance, is considered to be bioavailable (Baker and Croot, 2010; Ito et al., 2012; Mukhtar and Limbeck, 2013) and more chemically reactive in the atmosphere (Kebede et al., 2016; Mao et al., 2017). Dissolved trace elements are typically referred to as the fraction of elements which can pass through a filter with a certain pore size (usually 0.2–0.22 or 0.45 µm) after aerosol particles are dissolved in certain aqueous solutions (Boyd and Ellwood, 2010; Ito and Xu, 2014; Meskhidze et al., 2016; Myriokefalitakis et al., 2018). Solubility (or fractional solubility, to be more precise), which is defined as the ratio (in percentages) of the dissolved element to the total element (Baker et al., 2006; Sholkovitz et al., 2012), largely determines the bioavailability and reactivity of aerosol trace elements.

A wide range in the solubility has been reported in the literature for a given trace element in atmospheric aerosols; for example, the reported solubility of aerosol Fe ranges from < 1 % to > 90 % (Baker and Jickells, 2006; Sholkovitz et al., 2012). Such wide variabilities in aerosol trace element solubility, on the one hand, can be caused by a difference in sources and aging processes of aerosol particles examined (Ito et al., 2021; Meskhidze et al., 2019); on the other hand, they also stem from various leaching protocols which were used in different studies (Chen et al., 2006; Li et al., 2023; Upadhyay et al., 2011).

Various leaching protocols have been used in previous studies to extract dissolved aerosol trace elements, as summarized in a recent paper (Li et al., 2023). In brief, available leaching protocols broadly consist of two catalogues, including flow-through leaching and batch leaching. Flow-through leaching is instantaneous and typically has a contact time (between aerosol particles and the leaching solution used) of tens of seconds, and batch leaching usually has a much longer contact time (tens of minutes or longer). Compared to flow-through leaching, batch leaching is more widely used in atmospheric research. Furthermore, for batch leaching, various leaching solutions were used in previous studies, such as ultrapure water, filtered seawater, and formate/acetate buffers. Compared to filtered seawater and formate/acetate buffers, ultrapure water is more widely used in atmospheric research due to its simplicity and reproducibility (Li et al., 2023; Meskhidze et al., 2019); another important reason is that ultrapure water leaching does not introduce any other chemical species (except water) and can thus simultaneously extract water-soluble ions and organics for additional analysis.

Even for ultrapure water batch leaching, protocols used by different studies may still vary in agitation methods, contact time, and filter pore size; nevertheless, the effects of these factors on the reported solubility are not well understood. First, some labs use sonication to agitate the leaching solutions (Chen et al., 2006; Kumar and Sarin, 2010; Liu et al., 2021; Longo et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2020) and other labs use shaking (Baker et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2010; Li et al., 2022; Salazar et al., 2020). Sonication may cause changes in the chemical composition and formation of reactive oxygen species in the solution (Juretic et al., 2015; Miljevic et al., 2014); however, it remains to be examined whether sonication changes the solubility of aerosol trace elements. Second, filters with different pore sizes, including 0.2–0.22 and 0.45 µm (and 0.02 µm to a less extent), are employed to filter the leaching solutions, contributing to the uncertainties in the reported solubility; however, the effects of filter pore size have seldom been experimentally examined. Third, some studies (Li et al., 2023; Mackey et al., 2015) suggested that contact time (2–8 h) could also influence the reported solubility.

In the present work, using aerosol particles collected at a suburban site close to the coastline of the northwest Pacific, we investigated to which extent different ultrapure water batch leaching protocols would affect reported aerosol trace element solubility. In the first part of this work, we examine the effects of agitation (shaking vs. sonication), filter pore size (0.22 vs. 0.45 µm), and contact time (1 vs. 2 h) on the reported solubility of nine aerosol trace elements. In the second part, we compare solubility determined using protocols commonly adopted by four labs. The four labs all use ultrapure water batch leaching, but the leaching protocols they use differ in the agitation method, contact time, and/or filter pore size.

2.1 Sample collection and distribution

We collected aerosol samples between 18 March and 22 April 2023 in Qingdao, a coastal city in northern China, typically impacted by desert dust and anthropogenic aerosols in spring. As described elsewhere (Zhang et al., 2022), aerosol sampling took place at a suburban site which was about 1.3 km from the coast. A custom-made high-volume aerosol sampler (ASM-1; flow rate of 1 m3 min−1) was deployed on a building roof (about 20 m above the ground) to collect PM10 samples. Aerosol sampling started at 08:00 LT (local time, GMT+8) each day and stopped at 07:30 LT on the next day, resulting in a sampling volume of 1410 m3. PM10 samples were collected on pre-cleaned Whatman 41 cellulose fiber filters (25 cm × 20 cm), which had very low backgrounds for trace elements (Morton et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2022). In total, we collected 26 filter samples, 4 sampling blanks, and 3 lab blanks: lab blanks were defined as pre-cleaned filters, and sampling blanks were defined as pre-cleaned filters which were placed in the aerosol sampler for 2 h when the sampling flow was off. The amounts of dissolved trace elements on blank filters were mostly below detection limits; in a few cases, the blank levels exceeded detection limits but were negligible when compared to the on-filter samples.

After aerosol collection, each filter was folded inward and placed into a clean polyethylene bag (12 in. × 9 in.; supplied by Sigma-Aldrich), which was used due to its low background (Morton et al., 2013) and then stored at −20 °C. A titanium punch was used to obtain 10 subsamples (47 mm in diameter) from each filter sample, and these subsamples were stored at −20 °C.

2.2 Measurement of total and dissolved trace elements

2.2.1 Total elements

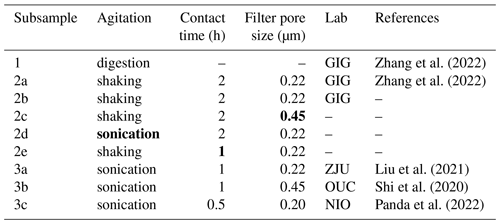

As shown in Table 1 and described below, for the 10 subsamples obtained from each original filter sample, the first subsample was digested to determine total elements, another 8 subsamples were leached using different protocols to determine dissolved elements, and the last subsample was reserved for any unforeseen purpose (but was not used at the end).

Table 1Overview of protocols used to digest and leach subsamples examined in this work. For each protocol, 26 subsamples were examined. In this table, Lab represents the lab whose protocol was adopted in this work to digest or leach subsamples. Experimental parameters for subsamples 2c–2e, when different from those for subsamples 2a, are in bold font.

Subsample 1 was digested in a Teflon jar, which contained a mixture of HNO3–HF–H2O2, using a microwave digestion system (Zhang et al., 2022). After digestion, we evaporated residual acids in the Teflon jar and filled it with 20 mL of HNO3 (1 %). Subsequently, we filtered the solution through a polyethersulfone membrane syringe filter (with a pore size of 0.22 µm) and then used ICP-MS (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; iCAP Q; Thermo Fisher) to measure nine trace elements, including Fe, Al, As, Cr, Cu, Mn, Pb, V, and Zn. These elements were chosen because they are important nutrients, toxic elements, or source tracers.

2.2.2 Dissolved elements

Subsample 2a was leached using the protocol adopted by the lab at the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry (GIG) (Li et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022, 2023). In brief, the subsample was shredded and then immersed in 20 mL of ultrapure water for 2 h, stirred using an orbital shaker; subsequently, the solution was filtered through a polyethersulfone membrane syringe filter (with a pore size of 0.22 µm). After that, the solution was immediately acidified with a small volume of high-purity HNO3 to contain 1 % HNO3 and then analyzed using ICP-MS to determine dissolved trace elements. Subsample 2b was leached using the same protocol as subsample 2a; the purpose was to examine whether aerosol particles were homogeneously distributed on different subsamples and to assess the repeatability of the GIG leaching protocol.

Subsamples 2c–2e were leached using protocols similar to that used to leach subsample 2a. As summarized in Table 1, the only difference from the protocol used to leach subsample 2a was the filter pore for 2c (0.45 µm vs. 0.22 µm for 2a), agitation method for 2d (sonication vs. shaking for 2a), and contact time for 2e (1 h vs. 2 h for 2a). The purpose of using subsamples 2c–2e is to examine the effects of filter pore size (0.22 vs. 0.45 µm), agitation method (shaking vs. agitation), and contact time (1 vs. 2 h) on the reported solubility.

Subsamples 3a, 3b, and 3c were leached using the protocols typically used by ZJU (Zhejiang University, China), OUC (Ocean University of China, China), and NIO (National Institute of Oceanography, India), respectively, in order to compare solubility determined by the GIG lab with those reported by the other three labs. Please note that subsample 3c was leached and analyzed by NIO, while subsamples 3a and 3b were leached and analyzed at GIG (using the ZJU and OUC protocols, respectively).

Subsample 3a was leached at GIG using the ZJU protocol (Liu et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). In brief, each subsample was shredded and immersed in 20 mL of ultrapure water, and the aqueous mixture was sonicated for 1 h during which the water bath temperature was kept below 30 °C; after that, the aqueous mixture was filtered using a polyethersulfone membrane syringe filter (pore size of 0.22 µm) and acidified for later ICP-MS analysis. Subsample 3b was leached at GIG using the OUC protocol (Shi et al., 2020), which is very similar to the ZJU method: the only difference is that the filter pore size was 0.45 µm for the OUC protocol and 0.22 µm for the ZJU protocol.

Subsample 3c was leached and analyzed at NIO using the NIO protocol (Panda et al., 2022). In brief, each subsample was shredded and placed into a pre-cleaned Savillex vial (50 mL); after that, the vial was filled with 20 mL of ultrapure water, capped, and then sonicated for 30 min to agitate the aqueous mixture (but in two cycles, with 15 min for each cycle, in order to maintain the water bath at room temperature). The aqueous mixture was then filtered through a Whatman PVDF syringe filter (pore size of 0.2 µm) and then acidified with HNO3 (2 % ) for later high-resolution ICP-MS analysis (Nu Instruments; Attom ES).

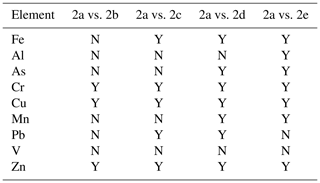

Subsamples 2a and 2b were identically leached using the protocol GIG normally uses, and the paired t test (α = 0.05) was employed to examine whether the difference in obtained solubility was significant. As summarized in Table 2, the difference in obtained solubility was not statistically significant between 2a and 2b for Fe, Al, As, Mn, Pb, and V; furthermore, Fig. S1 in the Supplement suggests good linear correlations in solubility between 2a and 2b for the six elements (r > 0.99), and the corresponding slopes (0.98 to 1.02) were very close to 1. For the other three elements (Cr, Cu, and Zn), although the difference in solubility was found to be statistically significant between 2a and 2b (Table 1), good linear correlations between the solubility were found (r > 0.97) and the slopes (1.00–1.06) were close to 1; therefore, the difference in solubility between 2a and 2b, if it existed, was small for Cr, Cu, and Zn.

Table 2Summary of the statistical analysis (paired t test; α = 0.05) which examined whether the difference in solubility obtained for different groups of subsamples is statistically significant. Solubility obtained for subsamples 2a is compared with those obtained for subsamples 2b, 2c, 2d, and 2e, respectively. Y: the difference is statistically different; N: the difference is not statistically different.

In summary, we conclude that the distribution of aerosol particles on a given original filter was homogeneous and that the protocol GIG normally uses had very good repeatability.

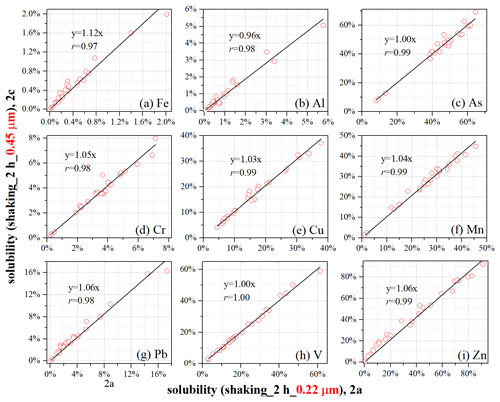

3.1 The effects of filter pore size

To examine the effects of filter pore size on the reported solubility, subsamples 2a and 2c were leached using very similar protocols, and the only difference was the pore size (0.22 µm for 2a; 0.45 µm for 2c) of the filters used (Table 1).

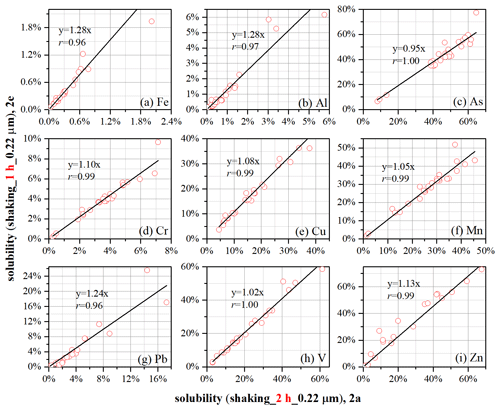

Figure 1The effects of filter pore size (0.22 µm for 2a; 0.45 µm for 2c) on measured element solubility. The only difference in protocols used to leach subsamples 2a and 2c is the filter pore size (0.22 versus 0.45 µm).

The difference in obtained solubility was not statistically significant between 2a and 2c for Al, As, Mn, and V (Table 2); moreover, good linear correlations between 2a and 2c were found for the four elements (Fig. 1), with slopes (0.96–1.04) very close to 1. For the other five elements (Fe, Cr, Cu, Pb, and Zn), the difference in solubility between 2a and 2c was found to be statistically significant; however, solubility between 2a and 2c was very well linearly correlated (Fig. 1), with slopes (1.03–1.12) close to or slightly larger than 1.

To conclude, among the nine elements we examined, the effects of filter pore size (0.22 vs. 0.45 µm) on reported solubility were found to be insignificant for four elements (Al, As, Mn, and V) and very small for the other five elements (Fe, Cr, Cu, Pb, and Zn).

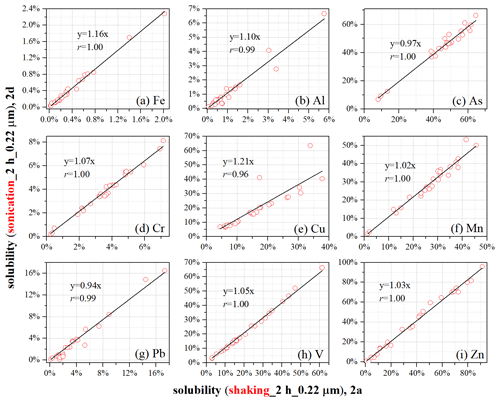

3.2 The effects of agitation

As shown in Table 1, the only difference between the protocol used to leach subsample 2a and that used to leach subsample 2d is the agitation method used (shaking for 2a and sonication for 2d), and solubilities obtained for subsamples 2a and 2d were compared to assess the effects of agitation methods on reported solubility.

Figure 2The effects of agitation (shaking for 2a; sonication for 2d) on measured element solubility. The only difference in protocols used to leach subsamples 2a and 2d is the agitation method (shaking vs. sonication).

Table 2 shows that the reported solubility between 2a and 2d was not statistically different for two elements (Al and V); in addition, good linear correlations between 2a and 2d were found for the two elements (Fig. 2), and these slopes (1.10 for Al and 1.05 for V) were quite close to 1. With respect to the other seven elements (Fe, As, Cr, Cu, Mn, Pb, and Zn), on the one hand, the difference in solubility between 2a and 2d was found to be statistically significant; on the other hand, good linear correlations in solubility existed between 2a and 2d (Fig. 2), and these slopes were in the range of 0.94–1.21.

In summary, we found that the choice of agitation methods (shaking vs. sonication) had no measurable (for Al and V) or small effects (for Fe, As, Cr, Cu, Mn, Pb, and Zn) on the reported solubility.

3.3 The effects of contact time

To assess the impacts of contact time on reported solubility, subsamples 2a and 2e were leached using very similar protocols, and the only difference was contact time (2 h for 2a; 1 h for 2e). We examined the effects of the contact time of these two, as the contact time was 2 h for the GIG protocol and 0.5–1 h for ZJU, OUC, and NIO protocols (Table 1).

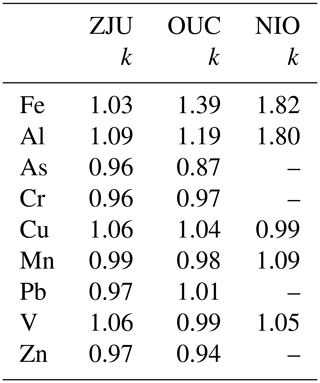

Figure 3The effects of contact time (1 h for 2a; 2 h for 2e) on measured element solubility. The only difference in protocols used to leach subsamples 2a and 2e is the contact time (1 h versus 2 h).

As shown in Table 2, the reported solubility was not statistically different between 2a and 2e for Pb and V; moreover, good linear relationships between 2a and 2e were found for the two elements (Fig. 3), with slopes close to 1 (1.24 for Pb and 1.02 for V). For the other seven elements, their solubility was found to be statistically significant between 2a and 2e (Table 2); nevertheless, for each of the seven elements, the solubility reported for 2a was very well linearly correlated with that reported for 2e (Fig. 3), and the slopes were close to 1 (in the range of 0.95–1.28).

To summarize, our present work suggests that the increase in contact time from 1 to 2 h would have insignificant or small effects on reported solubility. Using a different set of aerosol samples, our previous work (Li et al., 2023) compared the measured solubility obtained with longer contact time (4 and 8 h) to that obtained with a contact time of 2 h. As shown in Table S1, an increase in contact time from 2 to 4 h would cause a significant increase in solubility, on average by a factor of ∼ 1.3 for Zn to ∼ 3.1 for As (Li et al., 2023). It is still not clear why the increase in contact time from 1 to 2 h would not cause significant change in aerosol trace element solubility, while the increase in contact time from 2 to 4 h would; this is probably because for a given element, a different speciation has different dissolution kinetics.

3.4 Comparison of solubility obtained using protocols commonly used by four labs

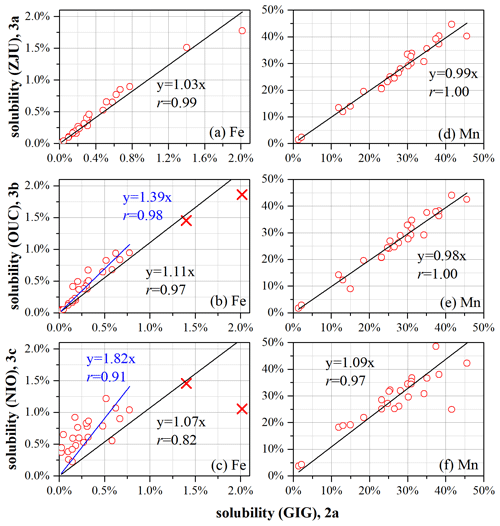

We further compared solubility determined using the GIG protocol with those determined using the ZJU, OUC, and NIO protocols. Table 3 summarizes the slopes obtained from the correlation analysis (Figs. 4 and S2–S8). The NIO lab measured 11 elements, among which 5 elements (Fe, Al, Cu, Mn, and V) were measured using the other three protocols; as a result, the solubility of these five elements determined using the NIO protocol was compared with those determined using the GIG protocol.

Table 3Correlations between solubility determined using the GIG protocol and that determined using ZJU, OUC, and NIO protocols. Here, only the slopes (k) are provided.

Figure 4Solubility of Fe and Mn determined using the GIG protocol vs. those determined using ZJU, OUC, and NIO protocols: (a) Fe (GIG vs. ZJU), (b) Fe (GIG vs. OUC), (c) Fe (GIG vs. NIO), (d) Mn (GIG vs. ZJU), (e) Mn (GIG vs. OUC), and (f) Mn (GIG vs. NIO). Black lines represent fitting when all the data points are included, and blue lines represent fitting when outliers (represented by red crosses) are excluded.

With respect to Fe solubility, GIG results were very well correlated with ZJU results (r = 0.99; Fig. 4a) and the slope was found to be 1.03, suggesting good agreement between GIG and ZJU; GIG results were also well correlated with, while overall larger than OUC results (r = 0.98, Fig. 4b), and the slope was determined to be 1.39. Good correlation was also found between GIG and NIO results (r = 0.91, Fig. 4c), and the slope was determined to be 1.82, indicating that Fe solubility determined using the NIO protocol was larger than that determined using the GIG protocol. Similarly, with respect to Al solubility (Fig. S2 and Table 3), the GIG results were well correlated with ZJU, OUC, and NIO results, and correlations were best for ZJU (r = 0.99) and moderate for NIO (r = 0.93); in addition, the slopes were determined to be 1.09, 1.19, and 1.80 for ZJU, OUC, and NIO results, respectively.

With respect to Cu (Fig. S5), Mn (Fig. 4d–f), and V (Fig. S7), their solubility determined using the ZJU, OUC, and NIO protocols was well correlated with that determined using the GIG protocol, and the slopes obtained from correlation analysis, which ranged from 0.98 to 1.09 (Table 3), were all close to 1.

Since As, Cr, Pb, and Zn were not measured using the NIO protocol, we only compared GIG results with ZJU and OUC results for these four elements. As shown in Figs. S3, S4, S6, and S8, the solubilities of As, Cr, Pb, and Zn determined using ZJU and OUC protocols were well correlated with that determined using the GIG protocol, and the slopes (0.87–1.01; as summarized in Table 3) were close to 1.

To summarize, although the four ultrapure water batch leaching protocols differ in the agitation method, contact time, and/or filter pore size (shaking, 2 h contact time, 0.22 µm filter pore size for GIG; sonication, 1 h contact time, 0.22 µm filter pore size for ZJU; sonication, 1 h contact time, 0.45 µm filter pore size for OUC; and sonication, 0.5 h contact time, 0.2 µm filter pore size for NIO), for the nine elements examined in this intercomparison study, their solubility determined using the four protocols in general showed good agreement. This is consistent with the results presented in Sect. 3.1–3.3, where we find that the effects of the agitation method (shaking vs. sonication), contact time (1 vs. 2 h), and filter pore size (0.22 vs. 0.45 µm) are rather limited. The solubilities of Fe and Al determined using the NIO protocol deviated considerably from those determined using the GIG protocol, probably because Fe and Al solubilities were very low (mostly < 2 %), and a small change in leaching protocol may cause significant change in the amounts of Fe and Al dissolved.

Ultrapure water batch leaching is widely used in atmospheric research to determine aerosol trace element solubility, and the specific leaching protocols used in different labs can still vary in agitation methods, contact time, and filter pore size. It is yet unclear to which extent the difference in these experimental parameters would affect the reported aerosol trace element solubility; in other words, it remains to be examined whether solubility reported by previous studies which used different ultrapure water batch leaching protocols is comparable.

We examined the effects of agitation methods, filter pore size, and contact time on the reported solubility of nine aerosol trace elements, including Fe, Al, As, Cr, Cu, Mn, Pb, V, and Zn. It was found that the difference in agitation methods (shaking vs. sonication), filter pore size (0.22 vs. 0.45 µm), and contact time (1 vs. 2 h) only led to a small and sometimes insignificant difference in the reported solubility. We further compared aerosol trace element solubility determined using four widely used ultrapure water leaching protocols which differ in agitation methods, filter pore size, and/or contact time, and, in general, the solubility determined using the four protocols was found to be in good agreement. Therefore, aerosol trace element solubility determined in previous studies using ultrapure water batch leaching may be comparable. Trace elements were analyzed using similar methods (ICP-MS) in our present work, and thus, we essentially only examined the effects of leaching protocols; nevertheless, other methods were also used by some previous studies to measure trace elements (Fang et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2022), probably causing additional uncertainties.

Aerosol trace element solubility is an operationally defined term (Baker and Croot, 2010; Meskhidze et al., 2019) that strongly depends on the leaching protocol employed. A number of leaching protocols have been used in previous studies to extract dissolved trace elements, making it very challenging to compare solubility reported in different studies (Perron et al., 2024). In order to reduce uncertainties in aerosol trace element solubility, it is necessary to formulate standard operating procedures for frequently used aerosol leaching protocols. Our current work suggests that although ultrapure water batch leaching protocols used by different labs vary in specific experimental parameters, the determined aerosol trace element solubility shows good agreement; furthermore, ultrapure water batch leaching is operationally simple and does not introduce any other chemical species which may interfere with the analysis of water-soluble inorganic ions and organics. Therefore, we recommend that ultrapure water batch leaching be one of the reference leaching schemes. We note that large difference in solubility determined using the four common leaching protocol we examined was also observed for Fe and Al (Table 1); moreover, the experimental parameters examined in this work do not cover the whole range used by various ultrapure water batch leaching protocols used in previous studies. As a result, before a standard operating procedure can be formulated for ultrapure water batch leaching, the community will need to reach consensus on agitation methods, contact time, and filter pore size, and further intercomparison studies, preferentially with more labs involved, will be very helpful.

Data are available upon request from Mingjin Tang (mingjintang@gig.ac.cn).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-3147-2024-supplement.

RL: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (original draft, review, and editing); PPP: formal analysis and investigation; YC: investigation; ZZ: investigation; FW: investigation and supervision; YZ: resources; HM: resources; YR: resources and supervision; AK: resources, writing (review and editing), and supervision; MT: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing (original draft, review, and editing), and supervision.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Atmospheric Measurement Techniques. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “RUSTED: Reducing Uncertainty in Soluble aerosol Trace Element Deposition (AMT/ACP/AR/BG inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

The authors would like to thank Likun Xue and other colleagues at Shandong University for their assistance in aerosol sampling and the SCOR (Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research) Working Group 167 (Reduce the Uncertainty in Soluble aerosol Trace Element Deposition, RUSTED) for valuable discussion.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42321003 and 42277088), Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (grant no. 2024A04J6533), and Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2022A1515110371).

This paper was edited by Bin Yuan and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Al-Abadleh, H. A.: Iron content in aerosol particles and its impact on atmospheric chemistry, Chem. Commun., 60, 1840–1855, 2024.

Alexander, B., Park, R. J., Jacob, D. J., and Gong, S.: Transition metal-catalyzed oxidation of atmospheric sulfur: Global implications for the sulfur budget, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 114, D02309, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010486, 2009.

Baker, A. R. and Croot, P. L.: Atmospheric and marine controls on aerosol iron solubility in seawater, Mar. Chem., 120, 4–13, 2010.

Baker, A. R. and Jickells, T. D.: Mineral particle size as a control on aerosol iron solubility, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L17608, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026557, 2006.

Baker, A. R., Kelly, S. D., Biswas, K. F., Witt, M., and Jickells, T. D.: Atmospheric deposition of nutrients to the Atlantic Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 2296, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018518, 2003.

Baker, A. R., French, M., and Linge, K. L.: Trends in aerosol nutrient solubility along a west–east transect of the Saharan dust plume, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L07805, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL024764, 2006.

Boyd, P. W. and Ellwood, M. J.: The biogeochemical cycle of iron in the ocean, Nat. Geosci., 3, 675–682, 2010.

Chen, Y., Street, J., and Paytan, A.: Comparison between pure-water- and seawater-soluble nutrient concentrations of aerosols from the Gulf of Aqaba, Mar. Chem., 101, 141–152, 2006.

Dahmardeh Behrooz, R., Kaskaoutis, D. G., Grivas, G., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Human health risk assessment for toxic elements in the extreme ambient dust conditions observed in Sistan, Iran, Chemosphere, 262, 127835, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127835, 2021.

Dong, Z., Shao, Y., Jiao, X., Parteli, E., Wei, T., Li, W., and Qin, X.: Iron Variability Reveals the Interface Effects of Aerosol-Pollutant Interactions on the Glacier Surface of Tibetan Plateau, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 128, e2022JD038232, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JD038232, 2023.

Fang, T., Guo, H., Verma, V., Peltier, R. E., and Weber, R. J.: PM2.5 water-soluble elements in the southeastern United States: automated analytical method development, spatiotemporal distributions, source apportionment, and implications for heath studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 11667–11682, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-11667-2015, 2015.

Fang, T., Guo, H., Zeng, L., Verma, V., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Highly Acidic Ambient Particles, Soluble Metals, and Oxidative Potential: A Link between Sulfate and Aerosol Toxicity, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 2611–2620, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06151, 2017.

Gao, K., Chen, X., Li, X., Zhang, H., Luan, M., Yao, Y., Xu, Y., Wang, T., Han, Y., Xue, T., Wang, J., Zheng, M., Qiu, X., and Zhu, T.: Susceptibility of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to heart rate difference associated with the short-term exposure to metals in ambient fine particles: A panel study in Beijing, China, Sci. China Life Sci., 65, 387–397, 2022.

Gao, Y., Yu, S., Sherrell, R. M., Fan, S., Bu, K., and Anderson, J. R.: Particle-Size Distributions and Solubility of Aerosol Iron Over the Antarctic Peninsula During Austral Summer, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, e2019JD032082, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD032082, 2020.

Hsu, S.-C., Wong, G. T. F., Gong, G.-C., Shiah, F.-K., Huang, Y.-T., Kao, S.-J., Tsai, F., Candice Lung, S.-C., Lin, F.-J., Lin, I. I., Hung, C.-C., and Tseng, C.-M.: Sources, solubility, and dry deposition of aerosol trace elements over the East China Sea, Mar. Chem., 120, 116–127, 2010.

Ito, A. and Xu, L.: Response of acid mobilization of iron-containing mineral dust to improvement of air quality projected in the future, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 3441–3459, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-3441-2014, 2014.

Ito, A., Kok, J. F., Feng, Y., and Penner, J. E.: Does a theoretical estimation of the dust size distribution at emission suggest more bioavailable iron deposition?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L05807, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL050455, 2012.

Ito, A., Ye, Y., Baldo, C., and Shi, Z.: Ocean fertilization by pyrogenic aerosol iron, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 4, 30, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-021-00185-8, 2021.

Juretic, H., Montalbo-Lomboy, M., van Leeuwen, J., Cooper, W. J., and Grewell, D.: Hydroxyl radical formation in batch and continuous flow ultrasonic systems, Ultrason. Sonochem., 22, 600–606, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.07.003, 2015.

Kebede, M. A., Bish, D. L., Losovyj, Y., Engelhard, M. H., and Raff, J. D.: The Role of Iron-Bearing Minerals in NO2 to HONO Conversion on Soil Surfaces, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 8649–8660, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b01915, 2016.

Kumar, A. and Sarin, M. M.: Aerosol iron solubility in a semi-arid region: temporal trend and impact of anthropogenic sources, Tellus B, 62, 125–132, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2009.00448.x, 2010.

Li, R., Zhang, H., Wang, F., Ren, Y., Jia, S., Jiang, B., Jia, X., Tang, Y., and Tang, M.: Abundance and fractional solubility of phosphorus and trace metals in combustion ash and desert dust: Implications for bioavailability and reactivity, Sci. Total Environ., 816, 151495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151495, 2022.

Li, R., Dong, S., Huang, C., Yu, F., Wang, F., Li, X., Zhang, H., Ren, Y., Guo, M., Chen, Q., Ge, B., and Tang, M.: Evaluating the effects of contact time and leaching solution on measured solubilities of aerosol trace metals, Appl. Geochem., 148, 105551, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2022.105551, 2023.

Liu, L., Lin, Q., Liang, Z., Du, R., Zhang, G., Zhu, Y., Qi, B., Zhou, S., and Li, W.: Variations in concentration and solubility of iron in atmospheric fine particles during the COVID-19 pandemic: An example from China, Gondwana Res., 97, 138–144, 2021.

Longo, A. F., Feng, Y., Lai, B., Landing, W. M., Shelley, R. U., Nenes, A., Mihalopoulos, N., Violaki, K., and Ingall, E. D.: Influence of Atmospheric Processes on the Solubility and Composition of Iron in Saharan Dust, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 6912–6920, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02605, 2016.

Mackey, K. R. M., Chien, C.-T., Post, A. F., Saito, M. A., and Paytan, A.: Rapid and gradual modes of aerosol trace metal dissolution in seawater, Front. Microbiol., 5, 794, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00794, 2015.

Mahowald, N. M., Hamilton, D. S., Mackey, K. R. M., Moore, J. K., Baker, A. R., Scanza, R. A., and Zhang, Y.: Aerosol trace metal leaching and impacts on marine microorganisms, Nat. Commun., 9, 1–15, 2018.

Mao, J., Fan, S., Jacob, D. J., and Travis, K. R.: Radical loss in the atmosphere from Cu-Fe redox coupling in aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 509–519, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-509-2013, 2013.

Mao, J., Fan, S., and Horowitz, L. W.: Soluble Fe in Aerosols Sustained by Gaseous HO2 Uptake, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 4, 98–104, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00017, 2017.

Martin, L. R. and Hill, M. W.: The effect of ionic strength on the manganese catalyzed oxidation of sulfur(IV), Atmos. Environ., 21, 2267–2270, 1987.

Meskhidze, N., Johnson, M. S., Hurley, D., and Dawson, K.: Influence of measurement uncertainties on fractional solubility of iron in mineral aerosols over the oceans, Aeolian Res., 22, 85–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2016.07.002, 2016.

Meskhidze, N., Vlker, C., Al-Abadleh, H. A., Barbeau, K., and Ye, Y.: Perspective on identifying and characterizing the processes controlling iron speciation and residence time at the atmosphere-ocean interface, Mar. Chem., 217, 103704, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2019.103704, 2019.

Miljevic, B., Hedayat, F., Stevanovic, S., Fairfull-Smith, K. E., Bottle, S. E., and Ristovski, Z. D.: To Sonicate or Not to Sonicate PM Filters: Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Upon Ultrasonic Irradiation, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 48, 1276–1284, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2014.981330, 2014.

Morton, P. L., Landing, W. M., Hsu, S.-C., Milne, A., Aguilar-Islas, A. M., Baker, A. R., Bowie, A. R., Buck, C. S., Gao, Y., Gichuki, S., Hastings, M. G., Hatta, M., Johansen, A. M., Losno, R., Mead, C., Patey, M. D., Swarr, G., Vandermark, A., and Zamora, L. M.: Methods for the sampling and analysis of marine aerosols: results from the 2008 GEOTRACES aerosol intercalibration experiment, Limnol. Oceanogr.-Meth., 11, 62–78, 2013.

Mukhtar, A. and Limbeck, A.: Recent developments in assessment of bio-accessible trace metal fractions in airborne particulate matter: A review, Anal. Chim. Acta, 774, 11–25, 2013.

Myriokefalitakis, S., Ito, A., Kanakidou, M., Nenes, A., Krol, M. C., Mahowald, N. M., Scanza, R. A., Hamilton, D. S., Johnson, M. S., Meskhidze, N., Kok, J. F., Guieu, C., Baker, A. R., Jickells, T. D., Sarin, M. M., Bikkina, S., Shelley, R., Bowie, A., Perron, M. M. G., and Duce, R. A.: Reviews and syntheses: the GESAMP atmospheric iron deposition model intercomparison study, Biogeosciences, 15, 6659–6684, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-6659-2018, 2018.

Panda, P. P., Aswini, M. A., Bhatt, P., Srimuruganandam, B., Peketi, A., and Kumar, A.: Bioactive Trace Elements' Composition and Their Fractional Solubility in Aerosols from the Arabian Sea during the Southwest Monsoon, ACS Earth Space Chem., 6, 1969–1981, 2022.

Perron, M. M. G., Fietz, S., Hamilton, D. S., Ito, A., Shelley, R. U., and Tang, M.: Preface to the inter-journal special issue “RUSTED: Reducing Uncertainty in Soluble aerosol Trace Element Deposition”, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 165–166, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-165-2024, 2024.

Salazar, J. R., Cartledge, B. T., Haynes, J. P., York-Marini, R., Robinson, A. L., Drozd, G. T., Goldstein, A. H., Fakra, S. C., and Majestic, B. J.: Water-soluble iron emitted from vehicle exhaust is linked to primary speciated organic compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 1849–1860, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-1849-2020, 2020.

Shi, J., Guan, Y., Ito, A., Gao, H., Yao, X., Baker, A. R., and Zhang, D.: High Production of Soluble Iron Promoted by Aerosol Acidification in Fog, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2019GL086124, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086124, 2020.

Sholkovitz, E. R., Sedwick, P. N., Church, T. M., Baker, A. R., and Powell, C. F.: Fractional solubility of aerosol iron: Synthesis of a global-scale data set, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 89, 173–189, 2012.

Upadhyay, N., Majestic, B. J., and Herckes, P.: Solubility and speciation of atmospheric iron in buffer systems simulating cloud conditions, Atmos. Environ., 45, 1858–1866, 2011.

Wang, W., Liu, M., Wang, T., Song, Y., Zhou, L., Cao, J., Hu, J., Tang, G., Chen, Z., Li, Z., Xu, Z., Peng, C., Lian, C., Chen, Y., Pan, Y., Zhang, Y., Sun, Y., Li, W., Zhu, T., Tian, H., and Ge, M.: Sulfate formation is dominated by manganese-catalyzed oxidation of SO2 on aerosol surfaces during haze events, Nat. Commun., 12, 1993, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22091-6, 2021.

Wei, J., Yu, H., Wang, Y., and Verma, V.: Complexation of Iron and Copper in Ambient Particulate Matter and Its Effect on the Oxidative Potential Measured in a Surrogate Lung Fluid, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 1661–1671, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b05731, 2019.

Zhang, H., Li, R., Dong, S., Wang, F., Zhu, Y., Meng, H., Huang, C., Ren, Y., Wang, X., Hu, X., Li, T., Peng, C., Zhang, G., Xue, L., Wang, X., and Tang, M.: Abundance and Fractional Solubility of Aerosol Iron During Winter at a Coastal City in Northern China: Similarities and Contrasts Between Fine and Coarse Particles, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 127, e2021JD036070, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD036070, 2022.

Zhang, H., Li, R., Huang, C., Li, X., Dong, S., Wang, F., Li, T., Chen, Y., Zhang, G., Ren, Y., Chen, Q., Huang, R., Chen, S., Xue, T., Wang, X., and Tang, M.: Seasonal variation of aerosol iron solubility in coarse and fine particles at an inland city in northwestern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 3543–3559, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-3543-2023, 2023.

Zhu, Y., Li, W., Lin, Q., Yuan, Q., and Shi, Z.: Iron solubility in fine particles associated with secondary acidic aerosols in east China, Environ. Pollut., 264, 114769, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114769, 2020.

Zhu, Y., Li, W., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Liu, L., Xu, L., Xu, J., Shi, J., Shao, L., Fu, P., Zhang, D., and Shi, Z.: Sources and processes of iron aerosols in a megacity in Eastern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 2191–2202, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-2191-2022, 2022.