the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

New quantitative measurements and spectroscopic line parameters of ammonia in the 685–1250 cm−1 spectral region for atmospheric remote sensing

Jeremy J. Harrison

D. Chris Benner

V. Malathy Devi

Ammonia (NH3) is a toxic pollutant, generally linked to agricultural emissions, and plays a major role in the formation of fine aerosols which have a significant and detrimental effect on human health. NH3 is one of the most significant gases that can be monitored by satellite instruments orbiting the Earth, including the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) and the Cross-track Infrared Sounder (CrIS). The interpretation of these measured atmospheric spectra requires accurate radiative transfer modelling, which relies on the quality of the input spectroscopic line parameters.

In this work we present new high quality high-resolution infrared spectra of self- and air-broadened NH3 at 296 K using a Bruker IFS 125HR spectrometer and a 24.45 cm pathlength sample cell with silver chloride windows. Using a multispectrum fitting approach, we then determine new spectroscopic line parameters over the range 685 to 1250 cm−1 for the NH3 0100 00 0 s ← 0000 00 0 a and 0100 00 0 a ← 0000 00 0 s transitions associated with the v2 mode; the Q branches of these transitions are the strongest NH3 features observed in atmospheric spectra. Our analysis utilises the Voigt lineshape, with speed-dependent Voigt and Rosenkranz line mixing for the strongest lines. To date this is the most complete experimental and multispectrum analysis of air-broadened NH3 over this spectral region. Our derived spectroscopic line parameters reproduce the new measurements substantially better than line parameters from the HITRAN 2020 database, which were derived from a mixture of ab initio calculations and previous laboratory measurements. We have revised values for parameters such as line intensities and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths, in some cases by almost 10 %. We have substantially lowered the uncertainties of key parameters, such as line intensities. In addition to the measured speed dependence and Rosenkranz line mixing parameters, which we believe are the first reported for the v2 band of NH3 in air, we also determine a range of parameters for the v2 band that are not currently in HITRAN, for example self- and air-pressure-induced shifts. We expect these new parameters to provide a more accurate basis for incorporation into atmospheric radiative transfer models to measure NH3 concentrations from satellite.

- Article

(3898 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(5393 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Ammonia (NH3) is found throughout the universe, from the interstellar medium (Ho and Townes, 1983) to the atmospheres of exoplanets, e.g. GJ 504 b (Mâlin et al., 2025). Closer to home, it can be found throughout the Solar System, e.g. in the atmospheres of the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn (Irwin et al., 2025), and also in the Earth's atmosphere where it is the most abundant alkaline gas. On Earth, it is emitted through a range of anthropogenic sources (Sutton et al., 2008; Behera et al., 2013; Wyer et al., 2022) of which agriculture, mostly accounted for by livestock and nitrogen-based fertilisers, is responsible for over 80 % of the global total emissions (Van Damme et al., 2021). Atmospheric NH3 is responsible for a variety of negative environmental and health effects. It contributes to the eutrophication and acidification of aquatic ecosystems, causing adverse effects on a variety of different flora (Sutton et al., 2009; García-Gómez et al., 2014). Additionally, NH3 serves as a significant precursor to fine particulate matter, PM2.5 (Brunekreef et al., 2015; Megaritis et al., 2013; Thakrar et al., 2020). It is estimated that atmospheric NH3 accounts for 30 % and 50 % of the total production of PM2.5 in the US and Europe, respectively (Erisman and Schaap, 2004; Behera and Sharma, 2010; Bauer et al., 2016; Han et al., 2020). PM2.5 contributes to visibility degradation (Ting et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022) and, when inhaled, can cause a number of diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and lung cancer (Apte et al., 2018; Lelieveld et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2000).

Atmospheric NH3 can be monitored near the Earth's surface using a variety of in situ methods such as wet chemistry or spectroscopic techniques (Twigg et al., 2022). Increasingly over the last few decades, it has been possible to monitor NH3 by infrared spectrometers onboard satellites, such as the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) (Clarisse et al., 2009; Van Damme et al., 2014, 2018; Clarisse et al., 2019), the Cross-track Infrared Sounder (CrIS) (Shephard and Cady-Pereira, 2015), the Atmospheric InfraRed Sounder (AIRS) (Warner et al., 2016, 2017), and the Tropospheric Emission Spectrometer (TES) (Shephard et al., 2011). Among the most prominent NH3 features in the infrared used for remote sensing are the two Q branches of the ν2 ammonia band at ∼ 10.4 and 10.7 µm. Accurate retrievals of NH3 concentrations from the measurements recorded by the various instruments mentioned above depend upon our ability to model atmospheric radiative transfer, which in turn depends on the underlying NH3 spectroscopic line parameters. It is therefore crucially important that the line parameters for the ν2 NH3 band are both accurately and precisely characterised.

In 2013, a full re-analysis of 14NH3 spectroscopy was conducted (Down et al., 2013). In particular, line positions and intensities for the ν2 band were revised. This work led to the most recent significant spectroscopic update for NH3 in the HITRAN 2012 (Rothman et al., 2013) and GEISA 2015 (Jacquinet-Husson et al., 2016) databases. A study was also conducted to determine self- and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths at half-maximum (HWHM) for the ν2 14NH3 band for J ≤ 9 (Nemtchinov et al., 2004); these results were included in the HITRAN 2012 database. In the case of 14NH3 lines where J > 9, the self-broadened halfwidths at each K level are set to 0.5, and the air-broadened halfwidths at each K level (K ≤ 9) are assigned the corresponding values for the J = 9 levels, except for K > 9 levels for which set values are assigned to fit the trend for other K values. High resolution spectra of 15NH3 have been recorded (Canè et al., 2019, 2020), and line positions derived from these studies being included in the HITRAN 2020 database (Gordon et al., 2021) with line intensities derived through ab initio calculations (Yurchenko, 2015). Currently, no lines of other minor isotopologues of NH3, such as NH2D, are included in the HITRAN database.

In this work, we label vibrational states by v1v2v3v4l3l4li, where vn represents the quantum number of the nth vibrational mode. Unlike the non-degenerate modes ν1 and ν2, ν3 and ν4 are doubly degenerate and give rise to the vibrational angular momentum labels l3 and l4, respectively, which can take the values −v, , …, v−2, v. These two angular momenta couple to produce the total vibrational angular momentum, l. The v2 mode is associated with the inversional umbrella motion between the two equivalent equilibrium structures, and is considered a classic textbook example of quantum mechanical tunnelling. As a result of this large amplitude vibration, each energy level of ammonia splits into a symmetric and antisymmetric level. For this reason, vibrational states additionally require an inversion label, i, denoted by s or a depending on whether the state is symmetric or antisymmetric on inversion through the planar configuration. The rotational levels are characterised by J, the total angular momentum quantum number, and K, its component along the molecular axis, which can take the values 0, 1, 2, …, J.

In this work, we derive a set of new line parameters for the ν2 NH3 band, including positions, intensities, self- and air-broadened halfwidths and, for the first time, a complete set of self- and air-pressure-induced shifts, and, where possible, speed dependence and Rosenkranz line mixing parameters. Although this work has focused primarily on deriving new line parameters for the 0100 00 0 s ← 0000 00 0 a and 0100 00 0 a ← 0000 00 0 s transitions (excitation from the ground state to v2 = 1) of 14NH3, which are of particular importance for remote sensing, we have also derived line parameters within the 685–1250 cm−1 spectral window for the same transitions of 15NH3, alongside a variety of other less intense 14NH3 lines in the ν4, 2ν2 (first overtone), and ν2+ν4 (combination) bands. The line parameters for these weaker bands are more fully detailed in the Supplement. We note also that, due to the small range of pressures for the pure NH3 spectra in our analysis, the self parameters tend to have larger uncertainties than the air parameters, in particular the self-pressure-induced line shifts. The measurements and analysis were optimised for atmospheric remote sensing applications, and the NH3 amount fractions are small enough that the self contribution to the air-broadened spectra are smaller than the experimental uncertainty. The self-induced values were derived from the lower pressure pure NH3 spectra in the multispectrum fit.

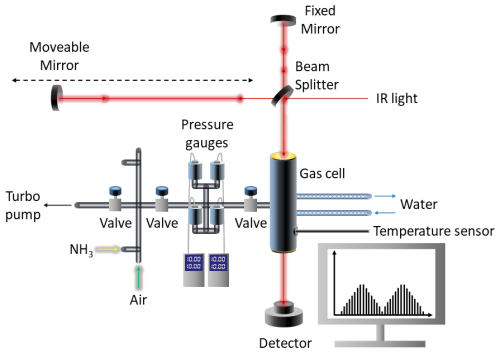

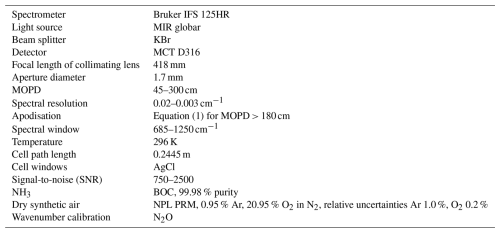

A new laboratory for the purposes of producing spectroscopic data for remote sensing of trace gases in the Earth's atmosphere has recently been set up at Space Park Leicester. Dubbed the SPectroscopy for ENvironmental SEnsing Research (SPENSER) facility, the principal instrument is a Bruker IFS 125HR spectrometer. In this work, we carried out measurements of pure and air-broadened NH3 samples at 296 K with a focus on the spectral window 685–1250 cm−1. A glass sample cell, situated inside the sample compartment of the spectrometer, was configured with high IR transmission AgCl windows. The cell pathlength was determined as 24.45 cm using high resolution measurements of the 0002 ← 0000 band of N2O and high accuracy line intensities from a previous study at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (Werwein et al., 2017). The pressure inside the absorption cell and gas line was monitored by four calibrated Inficon SKY CDG-45D manometers, with different full-scale pressures ranging from 0.1 to 1000 Torr. The temperature of the sample was maintained at a constant value of 296 K using a F32-HE Julabo circulator that flowed water around the outer jacket of the cell; the temperature was measured by four calibrated PRTs connected to an Isotech milliK precision thermometer and millisKanner channel expander. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1. The spectrometer settings and additional measurement information are listed in Table 1.

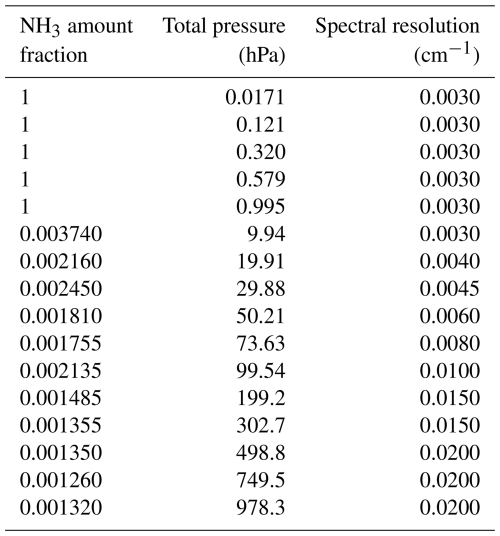

Table 1Spectrometer settings and measurement information for the pure and air-broadened NH3 spectra.

Sample gas mixtures were made from high purity gases, namely NH3 (BOC; 99.98 % purity) and dry synthetic air (primary reference material (PRM) from the National Physical Laboratory (NPL); 0.95 % Ar, 20.95 % O2 in N2, relative uncertainties Ar 1.0 %, O2 0.2 %). For the pure NH3 measurements, a spectral resolution of 0.003 cm−1 was used, defined as the Bruker instrument resolution of 0.9 per MOPD; MOPD = maximum optical path difference. For the air-broadened measurements, the spectral resolution was reduced according to the linewidth, with a lowest resolution of 0.02 cm−1 used where the total pressure approached 1000 hPa. Table 2 lists the pressures and resolutions selected for the measurements, which were optimised for the Earth's atmospheric conditions. These mixtures were found to be stable for many hours of scanning, with no signal degradation observed that might otherwise be attributed to reactions with the cell windows, for example. For the analysis, NH3 spectra were ratioed against appropriate empty cell spectra (taken at 0.03 cm−1 spectral resolution) to produce transmittance spectra. The generation of these transmittance spectra was handled by the Bruker OPUS program, which zero-fills the backgrounds to provide a point-by-point division on the grid of the single channel sample scans. These spectra were unapodised except for the highest resolution measurements (< 0.005 cm−1, equivalent to MOPD > 180 cm) for which the following apodisation function (ap) was applied (Devi et al., 2003):

where p is the path difference, and ap is defined as zero when p > MOPD. Finally, additional N2O spectra were recorded for the purposes of calibrating the wavenumber scales of the NH3 spectra. This is discussed in more detail in Sect. 3.

The pure and air-broadened ammonia spectra taken in this study were analysed using a nonlinear least-squares multispectrum fitting software package known as Labfit (Benner et al., 1995), which has an extensive history in deriving non-Voigt line parameters for remote sensing (e.g. Benner et al., 2016). In this work, line parameters were determined for both Voigt and speed-dependent Voigt lineshapes with Rosenkranz first order line mixing (Rosenkranz, 1988). The normalised Voigt lineshape with Rosenkranz line mixing is defined in Labfit (Benner et al., 1995; Letchworth and Benner, 2007) as:

where Y is the Rosenkranz line mixing parameter,

and

These are simply related to the complex probability function, W, by

where x and y are given by

and

In the above equations, ν−ν0 is the wavenumber detuning relative to the unperturbed line centre ν0, Γ0 is the Lorentz (collisional) halfwidth at half maximum, ΓD the Doppler halfwidth at half maximum, and Δ the pressure-induced shift of the line centre (so that represents the wavenumber detuning relative to the pressure-shifted line centre, ν0+Δ).

When the speed dependence of collisions is accounted for, the Voigt lineshape is modified into the speed-dependent Voigt profile. With the inclusion of Rosenkranz line mixing, the mathematical form of this profile is defined in Labfit (Benner et al., 1995; Ciurylo, 1998) by rewriting the Lorentz halfwidth as a function of v, defined as the ratio of the speed of an absorbing molecule to its most probable speed, and integrating over the full range of velocities. This leads to K and L being redefined as:

and

where

and Γ2 is the (quadratic) speed-dependence parameter for the Lorentz halfwidth. In this work, we do not consider the speed-dependence of the pressure-induced shifts. These shifts are expected to be small, and difficult to separate from the effects of line mixing.

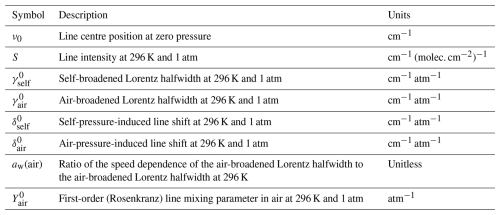

The parameters Γ0, Δ, and Y, introduced in Eqs. (2)–(10), are pressure dependent and can be expanded as

In the above expressions, γ0, δ0, and Y0 are defined at pref = 1 atm, p is the pressure in atmospheres, and x is the amount fraction of NH3 in the sample. As all measurements in this work were taken at 296 K, we have not considered temperature dependence terms in Eqs. (2)–(13). Also note that for each line in the spectrum, the current version of Labfit can only fit one speed dependence parameter (aw) and one Rosenkranz line-mixing parameter (Y0) in a solution, making no distinction between self and foreign contributions; however, the NH3 amount fractions in the high-pressure measurements are very small (less than ∼ 0.004) so that the self contributions to the air-broadened spectra are smaller than the experimental uncertainty. The definitions of the retrieved line parameters are summarised in Table 3.

In addition to line parameters, Labfit is able to correct during the analysis for minor imperfections in the spectra associated with the field of view or residual phase errors. The software can also fit spectral baselines using Chebyshev polynomials, and the zero level of individual spectra, and all spectra can be weighted in accordance with their individual signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs).

Using Labfit (Benner et al., 1995) it is possible to relate line positions via the corresponding upper and lower state rovibrational energies, and parameterise them in terms of the band centre and the rotational constants B, D, H, etc. By constraining line positions to these quantum mechanical expressions, fewer parameters are floated and correlations between parameters are reduced. This method has the advantage that blended lines can easily be separated using appropriate constraints. In Labfit, however, these position constraints are optimised for linear molecules such as carbon dioxide. Fitting spectra of ammonia, a symmetric rotor whose energy levels require an additional quantum number, K, adds an additional level of complexity to the problem that is too cumbersome without substantial modifications to the programming code. Therefore, for this work all line parameters, including positions, were solved on a line-by-line basis. This does present challenges, for example, when fitting two lines of similar intensity that are blended even in the lowest pressure spectra. In such cases, some parameters of one or both of the lines need to be fixed, as outlined in Sect. 4. In all cases, preference is given to fitting lines from the ν2 band.

The multispectrum fitting technique requires that all spectra are consistently calibrated prior to the spectral fitting. Lines present in the measured spectra originating from water absorption inside the evacuated portion of the spectrometer (not the cell) were used to provide a relative wavenumber calibration between spectra; in this case we utilised averages of single channel sample scans rather than the full transmittance spectra on account of the mismatch between sample and background spectral resolutions. The absolute calibration of the wavenumber scales of these water lines was determined by measuring a low-pressure spectrum of N2O at room temperature and calibrating against NIST heterodyne calibration tables (Maki and Wells, 1991).

The NH3 multispectrum fit was initialized using parameters from HITRAN 2020 (Gordon et al., 2021), and proceeded by fitting all pure sample spectra before adding the air-broadened spectra to the solution and floating selected parameters for all spectra simultaneously. Initial fits were carried out over the entire 685–1250 cm−1 region, however there was evidence from the saturated lines in the pure sample spectra that the zero level was not constant across this wide fitted interval; the current version of Labfit can only apply a single zero level offset correction to each spectrum. To counter this situation as much as possible, the spectra were split into three regions (685–900, 885–1015 and 1000–1250 cm−1), allowing three different offsets to be applied to each spectrum as required.

The approach taken here was to fit all absorption features within the fitted interval, and adjust positions, intensities, Lorentz halfwidths, pressure-induced shifts, Rosenkranz line mixing parameters, and quadratic speed dependence for each line separately. Line mixing and speed dependence parameters were included in the fit as judged by inspection of the fit residuals and the derived uncertainties determined by the fit.

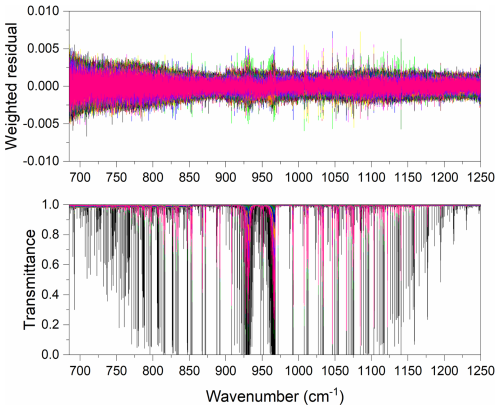

The final multispectrum fit for all 16 NH3 spectra (self- and air-broadened) over the entire 685–1250 cm−1 range is plotted in Fig. 2. The top panel shows the superimposed weighted spectral fit residuals (observed minus calculated), with the bottom panel showing the observed spectra. The vast majority of the residuals, including the entire Q branch region, are within ±0.5 %. The only exceptions are a small number of saturated features in the R branch region of the pure NH3 spectra, which are slightly greater. These small but persistent residuals are predominantly associated with the lowest pressure measurements, and are likely caused by small variations in the zero level for these spectra that are not adequately captured by Labfit (Benner et al., 1995).

Figure 2Overlay of all the transmittance spectra across the entire measured spectral region, 685–1250 cm−1, alongside their weighted fit residuals, defined as the difference between the observed and calculated spectra.

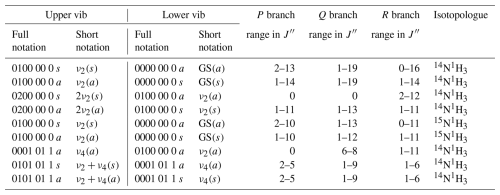

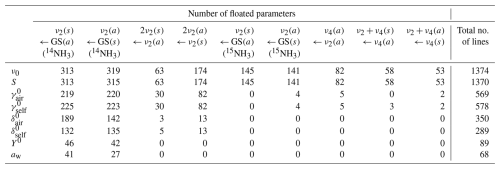

Table 4Main NH3 bands analysed in this study within the 685–1250 cm−1 spectral region. Some bands were only partially observed in the spectral window, for which only R branch lines were fit. The number ranges in columns 5 to 7 denote the range of analysed J′′ values for the observed transitions. However, a number of lines associated with K sub-levels are not included in the fit if the relevant lines are either outside the measured spectral window or have an intensity below the fitting threshold of 1 × 10−23 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 at 296 K.

Table 5The number of each type of fitted line parameter for the main NH3 bands analysed in this study.

The principal focus of this work is the ν2 band, however there are a number of other weaker bands present in the spectral region of interest. Table 4 lists the vibrational assignments of these bands along with the rotational lines and isotopologues that were included in the fit. In total, parameters were fit for 1374 lines with intensities above a threshold of 1 × 10−23 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1. For the weakest of these lines, only positions and intensities were determined; for the strongest, the whole suite of parameters listed in Table 3 were determined. In general, self- and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths were fit for lines with intensities above 4 × 10−22 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 and self- and air-pressure-induced shifts for lines with intensities above 1.5 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1. Selected lines of intensity > 7.5 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 were fit for one or both of speed dependence and Rosenkranz line mixing parameters. The total number of each type of line parameter determined for each of the bands listed in Table 4 is given in Table 5.

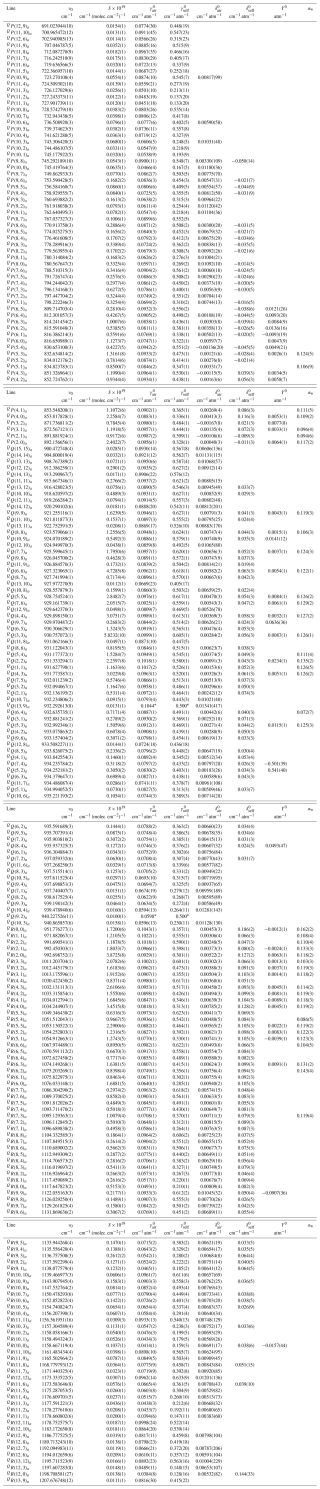

Table 6Measured parameters at 296 K for lines (labelled ) with spectral intensity > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 for the transition ν2(s)←GS(a). The numbers in parentheses are 1σ uncertainties in the units of the last digit listed. Missing entries indicate a lack of convergence for a given parameter, which was set to zero in the final solution. An asterisk (∗) indicates that the line parameter was fixed to its value in HITRAN 2020. A table of line parameters with spectral intensity < 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 for this transition is provided in the Supplement.

Table 7Measured parameters at 296 K for lines (labelled ) with spectral intensity > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 for the transition ν2(a)←GS(s). The numbers in parentheses are 1σ uncertainties in the units of the last digit listed. Missing entries indicate a lack of convergence for a given parameter, which was set to zero in the final solution. An asterisk (∗) indicates that the line parameter was fixed to its value in HITRAN 2020. A table of line parameters with spectral intensity < 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 for this transition is provided in the Supplement.

Tables 6 and 7 list the newly derived line parameters for lines with an intensity > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 at 296 K for the 0100 00 0 s ← 0000 00 0 a and the 0100 00 0 a ← 0000 00 0 s transitions. This intensity cut-off was selected because in all but two cases, it was the minimum required to enable floating of the pressure-induced line shift parameters. Throughout this work we will often refer to these transitions using the shorthand notation ν2(s)←GS(a) and ν2(a)←GS(s), respectively. Tables in the Supplement include line parameters for the lines with lower intensity, line parameters for the 15NH3 isotopologue, and the other transitions listed in Table 4.

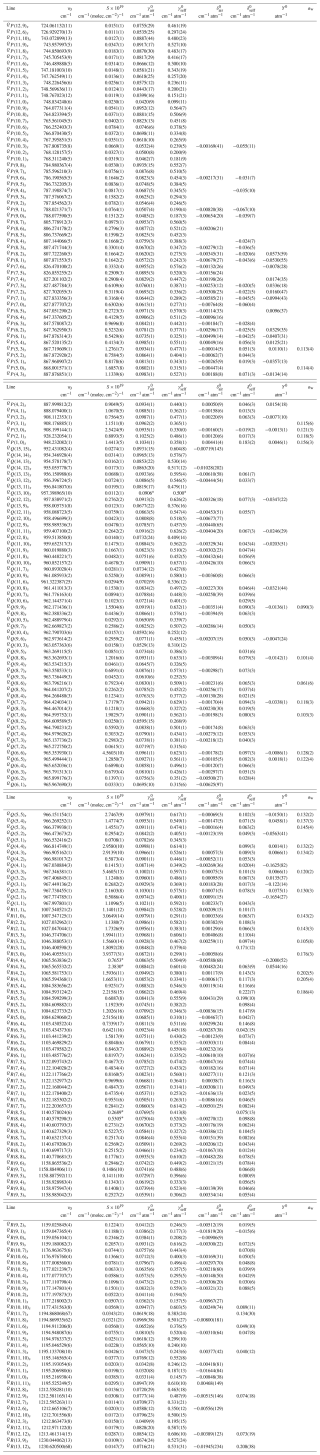

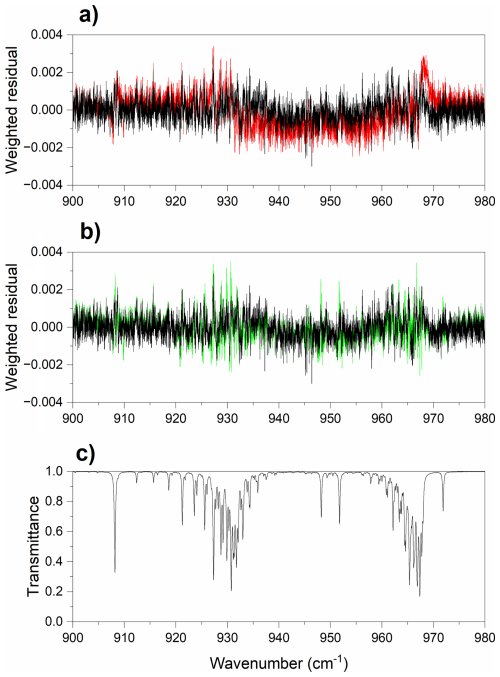

Figure 3Overlay of all the transmittance spectra across the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch, 955–970 cm−1, alongside their weighted residuals using (a) the new line parameters determined in the present study, and (b) the line parameters from the HITRAN 2020 database.

Figure 3 shows the spectral region covering the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch, with spectral residuals that result from our fit (Fig. 3a) compared to those obtained using the values from HITRAN 2020 (Fig. 3b). A significant improvement over the fit residuals in Fig. 3b are obtained in Fig. 3a as a result of using the line parameters determined from our multispectrum fit.

In order to analyse our measured dataset, we produced a number of plots of the individual line parameters, comparing our new line parameters for the NH3 ν2 band to those reported in the HITRAN 2020 database (Gordon et al., 2021). HITRAN is chosen here for the primary comparison because its NH3 linelist forms the basis for the majority of remote sensing datasets of NH3 in the Earth's atmosphere. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, the plots shown in the following sections display comparisons of data for the Q branch of the ν2(a)←GS(s) transition. Analogous comparison plots for the P and R branch for this transition, along with the P, Q and R branches of the ν2(s)←GS(a) transition, can be found in the Supplement. As long as sufficient parameters were available, similar comparison plots are shown in the Supplement for the other, less intense bands found in the measured spectral window. In every case, the uncertainties in the plots represent Labfit internal uncertainties at three standard deviations (3σ) for additional clarity. All uncertainties in tables are listed at 1σ.

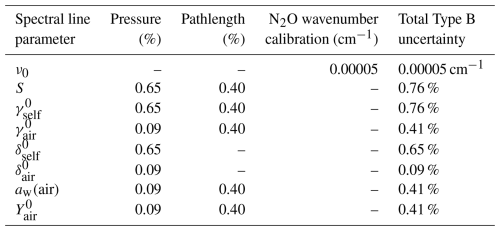

4.1 Uncertainties of the retrieved parameters

The line parameter uncertainties directly provided by Labfit (Benner et al. 1995) correspond to Type A uncertainties (Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, 2008), and are determined from the noise level of the spectrum, the spectral residuals, and the derived parameters in the solution. Labfit does not report Type B uncertainties (Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, 2008) of the line parameters arising from uncertainties in quantities such as the sample conditions (i.e., temperature, pressure, pathlength), the partition sums, issues with the instrumental lineshape of the spectrometer, and uncertainties arising from a poor choice of lineshape function, so we calculate these Type B contributions separately. The overall uncertainty can be found by adding the Type A and Type B contributions in quadrature and taking the square root.

Type B contributions are outlined in Table 8 and detailed below. The assumption we made in this study is that 1σ measurement uncertainties can be used to represent the maximum Type B uncertainty contributions to the derived line parameters; therefore all uncertainties presented here correspond to a 68 % confidence interval with a coverage factor k = 1. There are a number of contributions that are very small and so are not included in this table. For example, as the majority of parameters are temperature-dependent, there will be a very small uncertainty due to possible deviation of the true temperature from 296 K. An uncertainty of 0.05 K will contribute no more than 0.02 % to the Type B budget. Additionally, the stated NH3 purity was 99.98 %, so we can assume that the uncertainty on the absorber amount is no more than 0.02 %.

The NIST N2O lines (Maki and Wells, 1991) used for the wavenumber calibration in the present analysis have stated uncertainties of ∼ 0.00005 cm−1, which we can equate to a Type B uncertainty in the retrieved line positions. The other line parameters have contributions to their Type B uncertainty from uncertainties in pathlength and absorber pressure. The pathlength contribution is determined from the calibration process, namely 0.1 % uncertainty in N2O pressures, 0.24 % uncertainty in N2O line intensities (Devi et al., 2003), and 0.3 % resulting from the spectral fit.

Uncertainties in the pressures depend on which of the manometer pressure gauges were used for the pressure measurements and their calibrations; all were factory calibrated using reference gauges traceable to the PTB standard. During the multispectrum fitting procedure, some of the pressures for the pure spectra needed small adjustments on account of small inconsistencies in the spectral residuals. We made the assumption that the highest pure pressure (0.995 hPa) was the most reliable because it was made near the full scale of the (1 Torr) manometer; we spent the most attention in the lab to ensure this measurement was as accurate as possible. Inconsistencies in the lower pressures were assumed to arise from problems with outgassing in the cell; there was no evidence of this for the 0.995 hPa pure spectrum. The line intensity, self-broadened halfwidth, and self-pressure-induced shift parameters are most sensitive to the pure NH3 pressure measurements, which are estimated to have ∼ 0.65 % uncertainty (derived from the 0.995 hPa pure spectrum). The air-broadened halfwidths, air-pressure-induced shifts, speed dependence of the air-broadened halfwidth and line mixing parameters are most sensitive to the partial pressure of air. For the range 200–1000 mbar pressure of air used in our experiments we have assumed a representative estimation of 0.09 % uncertainty. Given the small amount fraction of NH3 in air (less than ∼ 0.004), the contribution of NH3 partial pressure uncertainties is minimal. Also note that the pressure-induced shifts do not depend on cell pathlength, and represent wavenumber differences so that the absolute wavenumber calibration has minimal contribution. Lastly, it should be noted that Rosenkranz line mixing used in the present analysis is only an approximation, and therefore the uncertainty contributions from its use cannot easily be quantified.

The total uncertainties in our line parameters compare favourably to those for the corresponding line parameters in HITRAN 2020. For the strongest lines, uncertainties in line positions are comparable, in the range 0.00001–0.0001 cm−1. For the strongest lines in the Q branches of the v2 band, the total uncertainties of our line intensities, and self- and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths are of the order of 1 %, a significant improvement over those reported in HITRAN 2020: 10 %–20 %, 2 %–5 %, and 2 %–5 %, respectively.

4.2 Line positions

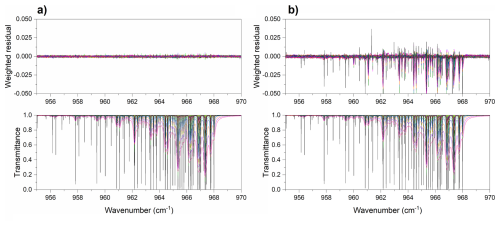

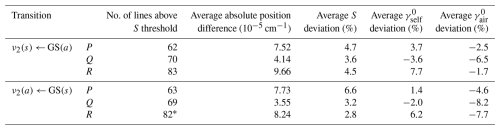

Newly determined line positions (ν0) have been compared with those from the HITRAN 2020 database, whose positions are based upon the analysis of Down et al. (2013), by plotting the position differences in Fig. 4a. For the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch lines up to J = 6, our line positions are higher by up to 0.00005 cm−1, comparable to the uncertainty (∼ 0.00005 cm−1) of the N2O lines from the NIST heterodyne wavenumber calibration tables (Maki and Wells, 1991) used in the wavenumber calibration. For lines with J > 6, our line positions tend to be lower than those reported in HITRAN 2020, although these lines are weaker with lower SNR in our overall analysis, and therefore the differences show more scatter. Table 9 reports that the average position difference between the new values and those from HITRAN is positive for the P, Q and R branches of both the ν2(a)←GS(s) and ν2(s)←GS(a) transitions, with the P and R branches displaying a greater shift in position than the Q branches.

Figure 4(a) Differences between the measured line positions and those from HITRAN 2020 (Gordon et al., 2021) for the NH3 ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch lines, with 3σ error bars, and (b) percentage deviations in intensity between the measured line intensities and those from HITRAN 2020 for the NH3 ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch lines. For both cases, only lines with intensity > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 are plotted.

Table 9Average absolute position differences, and percentage deviations of intensity and Lorentz halfwidths between parameters derived in this work and those in HITRAN 2020 (Gordon et al., 2021); the percentage deviations are calculated as 100 (Labfit HITRAN − 1). The values were determined from lines with intensity S > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 at 296 K. Halfwidth deviations were only determined for those lines with distinct halfwidth parameters for the analogous lines in HITRAN 2020, as opposed to set values discussed in Sect. 4.4.

∗ For the ν2(a)←GS(s) R branch, four lines (two pairs) were blended together. In order to fit the other line parameters, their intensities were fixed to the values from HITRAN 2020.

4.3 Line intensities

The line intensity calculation is driven by the five pure NH3 spectra in the multispectrum fit. Of these, the lowest pressure (0.0171 hPa) NH3 spectrum has no saturated lines; the transmittance of the strongest line is ∼ 0.17. Each line has at least one, usually more, unsaturated pure measurements from which to derive intensities. Because the lowest pressure measurements are less accurate, pressure values are adjusted in the fit so that the residuals align with those for the spectrum with the most accurate pressure (0.995 hPa). This adjustment is largely driven by the unsaturated lines that are present throughout multiple spectra. While Fig. 4a shows differences between our measured line positions and those from HITRAN 2020 (Gordon et al., 2021) for the NH3 ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch lines, Fig. 4b shows a plot of the percentage deviations of our measured spectral line intensities (S) against those from the HITRAN 2020 database (Gordon et al., 2021), again with intensities based on the work of Down et al. (2013). The scatter in percentage deviation as J increases is a consequence of the relative decrease in SNR for these high-J lines. Overall, our line intensities are slightly higher than those in HITRAN 2020. Considering only lines with S > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 at 296 K, we report an average increase in S of 3.4 % for lines in the two ν2←GS Q branches. Similar increases of 3 %–7 % are observed for the P and R branches; see Table 9 for further information.

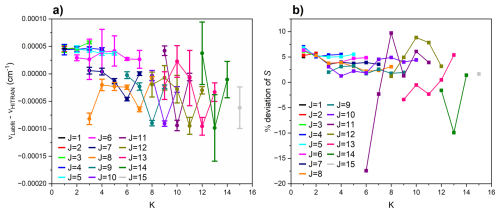

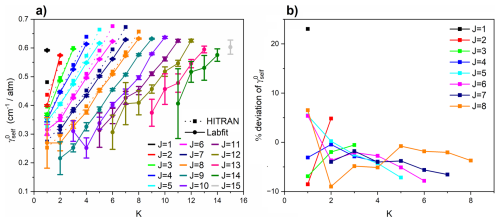

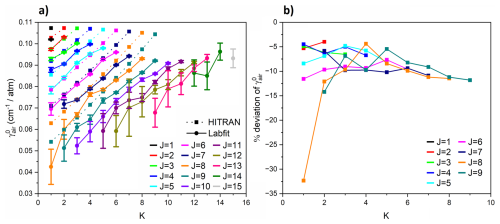

4.4 Self- and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths

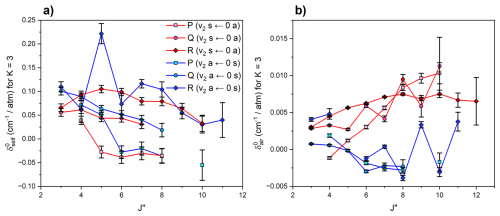

Figures 5a and 6a show the present measured self- () and air- () broadened halfwidths for all lines with intensity > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 at 296 K compared to the corresponding values from HITRAN 2020, which were derived by Nemtchinov et al. using a polynomial function of m and K, apparently only from measurements in the P and R branches of the ν2 band (Nemtchinov et al., 2004). Our measured values are found to show the same general trend, with both and increasing with K for the same J value. However, there are notable differences between the magnitudes of our halfwidths and those from HITRAN. Average percentage deviations of our measured parameters from HITRAN for the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch are plotted in Figs. 5b and 6b, with averages for other branches listed in Table 9 for both and . We observe significant deviations from the Nemtchinov-derived values, 4 %–10 % for and 2 %–8 % for . Analysis of the individual branches shows that the are 2 %–4 % lower than the Nemtchinov values in the Q branches but 1 %–4 % and 6 %–8 % higher for the P and R branches, respectively. The percentage deviations demonstrate a consistent pattern of overestimation by HITRAN 2020; our values are 2 %–5 %, 6 %–8 %, and 2 %–8 % lower for the P, Q, and R branches, respectively. In addition, we report values of the halfwidth parameters for J′′ > 8 for the first time. Previously, in HITRAN 2020, values for J′′ > 8 were set to 0.5, while values for J′′ > 8 were based on the widths reported for lower J values, using an extrapolation of the width parameters determined by Nemtchinov et al. (2004).

Figure 5Plots of (a) self-broadened halfwidth, , and (b) percentage deviations from HITRAN of plotted against K for each J value of the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch. The Labfit values of are included with uncertainties of 3σ. For J > 8, HITRAN values for the self-broadened halfwidth were all set to 0.5, so percentage deviations have not been calculated for these cases.

Figure 6Plots of (a) air-broadened halfwidth, , and (b) percentage deviations from HITRAN of plotted against K for each J value of the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch. The Labfit values of are included with uncertainties of 3σ. For J > 9, HITRAN values for the air-broadened halfwidth were set to the same value as their corresponding K value at J = 9 (with values of K > 9 set to the value for K = 9), so percentage deviations have not been calculated for these cases.

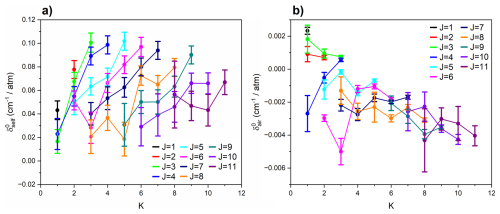

4.5 Self- and air-pressure-induced shifts

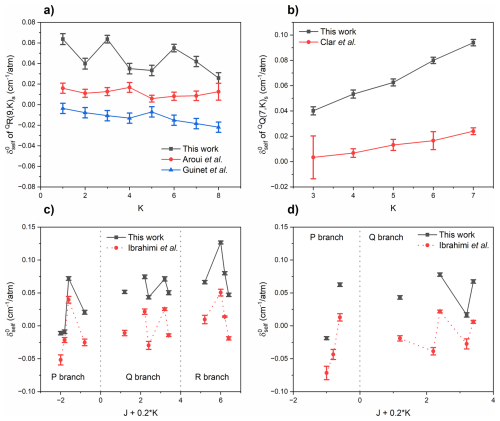

Figure 7 reports the self- () and air- () pressure-induced shifts for lines with an intensity > 1 × 10−21 cm−1 (molec. cm−2)−1 at 296 K. Since the HITRAN 2020 database does not list any values for or for NH3, we report values for these parameters for the complete ν2 band for the first time. Due to the optimisation of our experimental measurements for atmospheric conditions, i.e. the smaller range of NH3 pressures than air pressures, we observe larger errors in our determination of compared with .

Figure 7Plots of (a) self-pressure-induced shifts, , and (b) air-pressure-induced shifts, , against K for each J value of the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch. Measured values are plotted with uncertainties of 3σ. The HITRAN 2020 database does not include values for these parameters.

Figure 8Plots of (a) self-pressure-induced shifts, , and (b) air-pressure-induced shifts, , against J′′ for K = 3, for the P, Q and R branches of the ν2(s)←0(a) and ν2(a)←GS(s) transitions. The present measured values are given with uncertainties of 3σ. The HITRAN 2020 database does not include values for these parameters in this band.

According to Fig. 7a, the values of our measured parameters for the ν2(a)←GS(s) transition tend to decrease with increasing J, but increase with increasing K. A plot of against J′′ for only K = 3 levels is shown in Fig. 8a, and further indicates that the decrease in with increasing J holds for all three branches of the two ν2←GS transitions, with the exception of a single line in the R branch. Figure 8b indicates a tendency for values associated with the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch to decrease with both increasing J and K (apart from two more R branch lines). However, the plot of against J′′ for K = 3 in Fig. 8b suggests that the trend of with J is dependent on the symmetry of the transition, unlike for . For P, Q, R branches of the ν2(s)←GS(a) transition, increases with J′′, but for P, Q, R branches of the ν2(a)←GS(s) transition, decreases with J′′. There are not enough fitted and values for the other transitions to provide a more detailed analysis of these J-dependent observations.

Figure 9Comparison plots of self-pressure-induced shifts, , from our work and other papers, against K, for (a) the R branch of the ν2(s)←GS(a) transition, where J = 9; (b) the Q branch of the ν2(a)←GS(s) transition, where J = 7; (c) the P, Q and R branches of the ν2(s)←GS(a) transition; (d) the P and Q branches of the ν2(a)←GS(s) transition. Unlike other plots, uncertainties are plotted here as 1σ to better compare with the previous studies. The HITRAN 2020 database does not include values for these parameters in this band.

Although values of are not currently included in the HITRAN or GEISA databases, we were able to compare our values to previous data in the literature. Aroui et al. (2009) and Guinet et al. (2011) recorded measurements of several pure NH3 spectra at wavenumbers > 1000 cm−1 and at spectral resolutions of 0.0038 and 0.005 cm−1 respectively. They determined values for several lines in the ν2(s)←GS(a) R branch. Figure 9a shows a comparison plot of for our work against both studies, for values where J = 9. We predict higher values, an average increase of 0.0333 cm−1 atm−1 from Aroui et al. (2009) and 0.0570 cm−1 atm−1 from Guinet et al. (2011). The data from Guinet et al. (2011) does however obey the same trend of decreasing with K as found in our data.

With regards to the P and Q branches, Clar et al. (1988) and Ibrahimi et al. (1999) recorded measurements of several lines for both ν2(s)←GS(a) and ν2(a)←GS(s) transitions using tuneable diode laser spectrometers. Figure 9b shows a comparison plot of values against the data from Clar et al. (1988) for ν2(a)←GS(s), where J = 7. We observe an average increase of 0.0532 cm−1 atm−1 from the work of Clar et al. (1988), and the same general trend of increasing with increasing K for the Q branch. Figure 9c and d show comparison plots of against the values from Ibrahimi et al. (1999) for ν2(s)←GS(a) and ν2(a)←GS(s) respectively. We observe an average increase of 0.0545 cm−1 atm−1 from the work of Ibrahimi et al. (1999), and observe the same general trends of with J and K.

We found no studies reporting values, and thus cannot make any comparisons to our values.

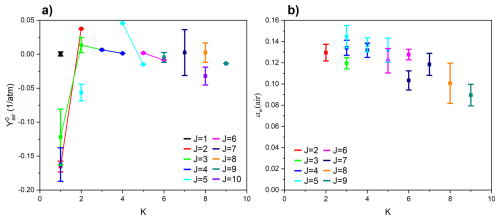

Figure 10Plots of (a) Rosenkranz line mixing parameter, , and (b) speed dependence of the halfwidth parameter, aw(air), against K for each J value of the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch. The present measured values are shown with uncertainties of 3σ. The HITRAN 2020 database does not include values for these line parameters of NH3.

4.6 Rosenkranz line mixing and speed dependence

Figure 10a shows the Rosenkranz line mixing parameters, , plotted against the quantum number K for lines of the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch where values were determinable. The largest values of for this transition occur for K =1 levels. The lines corresponding with the parameters in Fig. 10a span a wavenumber range of 1 cm−1, and there is significant overlap between the lines when air-broadened at pressures approaching 1000 hPa. Line mixing parameters are almost exclusively fit for the Q branches, which are more congested than the P and R branches.

Figure 10b provides a plot of the speed dependence of the width parameter, aw(air), where this parameter was determinable, against K for lines in the ν2(a)←GS(s) Q branch. The results show a decrease in aw as J and K increase, although this trend is not observed in the Q branch for the ν2(s)←GS(a), where aw remains constant across all values of J and K. We report an average value for aw of 0.131 for ν2(a)←GS(s) and 0.118 for ν2(s)←GS(a).

As an illustration of the benefit in floating both and aw(air) parameters in the multispectrum fit, the plots in Fig. 11 show the final spectral fit residuals for both ν2 Q branches, compared with residuals calculated from the same fit but with all and aw(air) values set to zero. It is clear that the inclusion of each parameter in the multispectrum fit improves the residuals, bringing them closer to zero.

Figure 11Comparison plots over the spectral region containing the ν2 Q branches (900–980 cm−1) of the weighted fit residuals for the measured highest-pressure spectrum (total pressure 978.3 hPa): (a) with (black) and without (red) the inclusion of Rosenkranz line mixing; (b) with (black) and without (green) the inclusion of speed dependence; panel (c) shows the measured laboratory transmittance spectrum.

We have carried out the most complete experimental and multispectrum analysis of air-broadened NH3 over the 675 to 1250 cm−1 spectral region to date. This spectral region covers the most intense NH3 features observed in atmospheric spectra, the 0100 00 0 s ← 0000 00 0 a and 0100 00 0 a ← 0000 00 0 s transitions of the v2 band. Our analysis utilises the Voigt and speed-dependent Voigt lineshapes (depending on the SNR of the lines), with Rosenkranz line mixing for congested Q-branches. In all, we derive line positions, line intensities, self- and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths, self- and air-pressure-induced line shifts, the speed dependence of the air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths, and first-order (Rosenkranz) line mixing parameters. Our derived spectroscopic line parameters reproduce the new laboratory measurements substantially better than those from the HITRAN 2020 database. We have revised values for parameters such as line intensities and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths, in some cases by almost 10 %. For the strongest lines, the total uncertainties of key parameters such as line intensities, and self- and air-broadened Lorentz halfwidths have been considerably improved to ∼ 1 %. In addition to the measured speed dependence and Rosenkranz line mixing parameters, which we believe are the first reported for the v2 band of NH3 in air, we also determine a range of parameters for the v2 band that are not currently in HITRAN, for example self- and air-pressure-induced shifts. We expect these new parameters to provide a more accurate basis for incorporation into atmospheric radiative transfer models to measure NH3 concentrations from satellite.

The Labfit code is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

The data from this paper are presented within the article itself and the supplementary information file.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-18-7421-2025-supplement.

JJH acquired the funding, designed the experiments and supervised the project. DJLC and JJH built the experimental setup and carried out the measurements. DJLC performed the formal data analysis. DCB developed the Labfit software program, which was used for data analysis. DCB and VMD provided resources, software and guidance for using the Labfit software program. DJLC wrote the initial draft of the published work. JJH, DCB and VMD reviewed and edited the published work.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This study was funded as part of the UK Research and Innovation Natural Environment Research Council's support of the National Centre for Earth Observation. We thank Manfred Birk at Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) for providing us with the spectroscopic sample cell, although this was later rebuilt due to a breakage.

This research has been supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (grant nos. NE/R016518/1 and NE/Y006216/1).

This paper was edited by Gabriele Stiller and reviewed by Chris Boone and one anonymous referee.

Apte, J. S., Brauer, M., Cohen, A. J., Ezzati, M., and Arden Pope III, C.: Ambient PM2.5 Reduces Global and Regional Life Expectancy, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 5, 546–551, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00360, 2018.

Aroui, H., Laribi, H., Orphal, J., and Chelin, P.: Self-broadening, self-shift and self-mixing in the ν2, 2ν2 and ν4 bands of NH3, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 110, 2037–2059, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2009.05.002, 2009.

Bauer, S. E., Tsigaridis, K., and Miller, R.: Significant atmospheric aerosol pollution caused by world food cultivation, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 5394–5400, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL068354, 2016.

Behera, S. N. and Sharma, M.: Investigating the potential role of ammonia in ion chemistry of fine particulate matter formation for an urban environment, Sci. Total Environ., 408, 3569–3575, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.04.017, 2010.

Behera, S. N., Sharma, M., Aneja, V. P., and Balasubramanian, R.: Ammonia in the atmosphere: a review on emission sources, atmospheric chemistry and deposition on terrestrial bodies, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser., 20, 8092–8131, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-013-2051-9, 2013.

Benner, D. C., Rinsland, C. P., Devi, V. M., Smith, M. H., and Atkins, D.: A multispectrum nonlinear least squares fitting technique, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 6, 705–721, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4073(95)00015-D, 1995.

Benner, D. C., Devi, V. M., Sung, K., Brown, L. R., Miller, C. E., Payne, V. H., Drouin, B. J., Yu, S., Crawford, T. J., Mantz, A. W., Smith, M. H., and Gamache, R. R.: Line parameters including temperature dependences of air- and self-broadened line shapes of 12C16O2: 2.06-µm region, J. Mol. Spectrosc., 326, 21–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jms.2016.02.012, 2016.

Brunekreef, B., Harrison, R. M., Künzli, N., Querol, X., Sutton, M. A., Heederik, D. J. J., and Sigsgaard, T.: Reducing the health effect of particles from agriculture, Lancet Respir. Med., 3, 831–832, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00413-0, 2015.

Canè, E., Di Lonardo, G., Fusina, L., Tamassia, F., and Predoi-Cross, A.: The v2 = 1, 2 and v4 = 1 bending states of 15NH3 and their analysis at experimental accuracy, J. Chem. Phys., 150, 194301, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5088751, 2019.

Canè, E., Di Lonardo, G., Fusina, L., Tamassia, F., and Predoi-Cross, A.: Spectroscopic characterization of the v2 = 3 and v2 = v4 = 1 states for 15NH3 from high resolution infrared spectra, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 250, 106987, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2020.106987, 2020.

Ciurylo, R.: Shapes of pressure- and Doppler-broadened spectral lines in the core and near wings, Phys. Rev. A, 58, 1029, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.58.1029, 1998.

Clar, H.-J., Schieder, R., Winnewisser, G., and Yamada, K. M. T.: Pressure broadening and lineshifts in the ν2 band of NH3, J. Mol. Struct., 190, 447–456, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2860(88)80303-X, 1988.

Clarisse, L., Clerbaux, C., Dentener, F., Hurtmans, D., and Coheur, P.-F.: Global ammonia distribution derived from infrared satellite observations, Nat. Geosci., 2, 479–483, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo551, 2009.

Clarisse, L., Van Damme, M., Gardner, W., Coheur, P.-F., Clerbaux, C., Whitburn, S., Hadji-Lazaro, J., and Hurtmans, D.: Atmospheric ammonia (NH3) emanations from Lake Natron's saline mudflats, Sci. Rep., 9, 4441, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39935-3, 2019.

Devi, V. M., Benner, D. C., Smith, M. A. H., Brown, L. R., and Dulick, M.: Absolute intensity measurements of the laser bands near 10 µm, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 76, 393–410, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4073(02)00067-5, 2003.

Down, M. J., Hill, C., Yurchenko, S. N., Tennyson, J., Brown, L. R., and Kleiner, I.: Re-analysis of ammonia spectra: Updating the HITRAN 14NH3 database, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 130, 260–272, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2013.05.027, 2013

Erisman, J. W. and Schaap, M.: The need for ammonia abatement with respect to secondary PM reductions in Europe, Environ. Pollut., 129, 159–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2003.08.042, 2004.

García-Gómez, H., Garrido, J. L., Vivanco, M. G., Lassaletta, L., Rábago, I., Àvila, A., Tsyro, S., Sánchez, G., González Ortiz, A., González-Fernández, I., and Alonso, R.: Nitrogen deposition in Spain: modeled patterns and threatened habitats within the Natura 2000 network, Sci. Total Environ., 485–486, 450–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.112, 2014.

Gordon, I. E., Rothman, L. S., Hargreaves, R. J., Hashemi, R., Karlovets, E. V., Skinner, F. M., Conway, E. K., Hill, C., Kochanov, R. V., Tan, Y., Wcislo, P., Finenko, A. A., Nelson, K., Bernath, P. F., Birk, M., Boudon, V., Campargue, A., Chance, K. V., Coustenis, A., Drouin, B. J., Flaud, J.-M., Gamache, R. R., Hodges, J. T., Mlawer, E. J., Nikitin, A. V., Perevalov, V. I., Rotger, M., Tennyson, J., Toon, G. C., Tran, H., Tyuterev, V. G., Adkins, E. M., Baker, A., Barbe, A., Cane, E., Csaszar, A. G., Dudaryonok, A., Egorov, O., Fleisher, A. J., Fleurbaey, H., Foltynowicz, A., Furtenbacher, T., Harrison, J. J., Hartmann, J.-M., Horneman, V.-M., Huang, X., Karman, T., Karns, J., Kassi, S., Kleiner, I., Kofman, V., Kwabia-Tchana, F., Lavrentieva, N. N., Lee, T. J., Long, D. A., Lukashevskaya, A. A., Lyulin, O. M., Makhnev, V. Yu., Matt, W., Massie, S. T., Melosso, M., Mikhailenko, S. N., Mondelain, D., Muller, H. S. P., Naumenko, O. V., Perrin, A., Polyansky, O. L., Raddaoui, E., Raston, P. L., Reed, Z. D., Rey, M., Richard, C., Tobias, R., Sadiek, I., Schwenke, D. W., Starikova, E., Sung, K., Tamassia, F., Tashkun, S. A., Vander Auwera, J., Vasilenko, I. A., Vigasin, A. A., Villanueva, G. L., Vispoel, B., Wagner, G., Yachmenev, A., and Yurchenko, S. N.: The HITRAN2020 molecular spectroscopic database, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 277, 107949, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2021.107949, 2021.

Guinet, M., Jeseck, P., Mondelain, D., Pepin, I., Janssen, C., Camy-Peyret, C., and Mandin, J. Y.: Absolute measurements of intensities, positions and self-broadening coefficients of R branch transitions in the ν2 band of ammonia, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 112, 1950–1960, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2011.03.015, 2011.

Han, X., Zhu, L., Liu, M., Song, Y., and Zhang, M.: Numerical analysis of agricultural emissions impacts on PM2.5 in China using a high-resolution ammonia emission inventory, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 9979–9996, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-9979-2020, 2020.

Ho, P. T. P. and Townes, C. H.: Interstellar Ammonia, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys., 21, 239–270, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.aa.21.090183.001323, 1983.

Ibrahimi, M., Babay, A., Lemoine, B., and Rohart, F.: Pressure-Induced Frequency Lineshifts in the ν2 Band of Ammonia: An Experimental Test of the Rydberg–Ritz Principle, J. Mol. Spectrosc., 193, 277–284, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsp.1998.7749, 1999.

Irwin, P. G. J., Hill, S. M., Fletcher, L. N., Alexander, C., and Rogers, J. H.: Clouds and Ammonia in the Atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn Determined From a Band-Depth Analysis of VLT/MUSE Observations, J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 130, e2024JE008622, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JE008622, 2025.

Jacquinet-Husson, N., Armante, R., Scott, N. A., Chédin, A., Crépeau, L., Boutammine, C., Bouhdaoui, A., Crevoisier, C., Capelle, V., Boonne, C., Poulet-Crovisier, N., Barbe, A., Benner, D. C., Boudon, V., Brown, L. R., Buldyreva, J., Campargue, A., Coudert, L. H., Devi, V. M., Down, M. J., Drouin, B. J., Fayt, A., Fittschen, C., Flaud, J.-M., Gamache, R. R., Harrison, J. J., Hill, C., Hodnebrog, Ø., Hu, S.-M., Jacquemart, D., Jolly, A., Jiménez, E., Lavrentieva, N. N., Liu, A.-W., Lodi, L., Lyulin, O. M., Massie, S. T., Mikhailenko, S., Müller, H. S. P., Naumenko, O. V., Nikitin, A., Nielsen, C. J., Orphal, J., Perevalov, V. I., Perrin, A., Polovtseva, E., Predoi-Cross, A., Rotger, M., Ruth, A. A., Yu, S. S., Sung, K., Tashkun, S. A., Tennyson, J., Tyuterev, Vl. G., Vander Auwera, J., Voronin, B. A., and Makie, A.: The 2015 edition of the GEISA spectroscopic database, J. Mol. Spectrosc., 327, 31–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jms.2016.06.007, 2016.

Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM): 100:2008 Evaluation of measurement data – Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement, https://doi.org/10.59161/JCGM100-2008E, 2008.

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D., and Pozzer, A.: The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale, Nature, 525, 367–371, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15371, 2015.

Letchworth, K. L. and Benner, D. C.: Rapid and accurate calculation of the Voigt function, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 107, 173–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2007.01.052, 2007.

Maki, A. G. and Wells, J. S.: Wavenumber calibration tables from heterodyne frequency measurements. NIST Special Publication 821, National Institute of Standard and Technology, Gaithersburg, https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.821, 1991.

Mâlin, M. Boccaletti, A., Perrot, C., Baudoz, P., Rouan, D., Lagage, P.-O., Waters, R., Güdel, M., Henning, T., Vandenbussche, B., Absil, O., Barrado, D., Charnay, B., Choquet, E., Cossou, C., Danielski, C., Decin, L., Glauser, A.M., Pye, J., Olofsson, G., Glasse, A., Patapis, P., Royer, P., Scheithauer, S., Serabyn, E., Tremblin, P., Whiteford, N., van Dishoeck, E. F., Ostlin, G., Ray, T. P., and Wright, G.: First unambiguous detection of ammonia in the atmosphere of a planetary mass companion with JWST/MIRI coronagraphs, Astron. Astrophys., 693, A315, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202452695, 2025.

Megaritis, A. G., Fountoukis, C., Charalampidis, P. E., Pilinis, C., and Pandis, S. N.: Response of fine particulate matter concentrations to changes of emissions and temperature in Europe, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 3423–3443, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-3423-2013, 2013.

Nemtchinov, V., Sung, K., and Varanasi, P.: Measurements of line intensities and half-widths in the 10-µm bands of 14NH3, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 83, 243–265, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4073(02)00354-0, 2004.

Rosenkranz, P. W.: Interference coefficients for overlapping oxygen lines in air, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 39, 287–297, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4073(88)90004-0, 1988.

Rothman, L. S., Gordon, I. E., Babikov, Y., Barbe, A., Benner, D. C., Bernath, P. F., Birk, M., Bizzocchi, L., Boudon, V., Brown, L. R., Campargue, A., Chance, K., Cohen, E. A., Coudert, L. H., Devi, V. M., Drouin, B. J., Fayt, A., Flaud, J. M., Gamache, R. R., Harrison, J. J., Hartmann, J. M., Hill, C., Hodges, J. T., Jacquemart, D., Jolly, A., Lamouroux, J., Le Roy, R. J., Li, G., Long, D. A., Lyulin, O. M., Mackie, C. J., Massie, S. T., Mikhailenko, S. N., Muller, H. S. P., Naumenko, O. V., Nikitin, A. V., Orphal, J., Perevalov, V. I., Perrin, A., Polovtseva, E. R., Richard, C., Smith, M. A. H., Starikova, E., Sung, K., Tashkun, S. A., Tennyson, J., Toon, G. C., Tyuterev, V. G., and Wagner, G.: The HITRAN2012 molecular spectroscopic database, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 130, 4–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2013.07.002, 2013.

Shephard, M. W. and Cady-Pereira, K. E.: Cross-track Infrared Sounder (CrIS) satellite observations of tropospheric ammonia, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 1323–1336, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-1323-2015, 2015.

Shephard, M. W., Cady-Pereira, K. E., Luo, M., Henze, D. K., Pinder, R. W., Walker, J. T., Rinsland, C. P., Bash, J. O., Zhu, L., Payne, V. H., and Clarisse, L.: TES ammonia retrieval strategy and global observations of the spatial and seasonal variability of ammonia, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 10743–10763, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-10743-2011, 2011.

Sutton, M. A., Erisman, J. W., Dentener, F., and Möller, D.: Ammonia in the environment: from ancient times to the present, Environ. Pollut., 156, 583–604, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2008.03.013, 2008.

Sutton, M. A., Reis, S., and Baker, S. M. H.: Atmospheric Ammonia: Detecting Emission Changes and Environmental Impacts, Springer Netherlands, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9121-6, 2009.

Thakrar, S. K., Balasubramanian, S., Adams, P. J., Azevedo, I. M. L., Muller, N. Z., Pandis, S. N., Polasky, S., Arden Pope III, C., Robinson, A. L., Apte, J. S., Tessum, C. W., Marshall, J. D., and Hill, J. D.: Reducing Mortality from Air Pollution in the United States by Targeting Specific Emission Sources, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 7, 639–645, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00424, 2020.

Ting, Y. C., Young, L. H., Lin, T. H., Tsay, S. C., Chang, K. E., and Hsiao, T. C.: Quantifying the impacts of PM2.5 constituents and relative humidity on visibility impairment in a suburban area of eastern Asia using long-term in-situ measurements, Sci. Total Environ., 818, 151759, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151759, 2022.

Twigg, M. M., Berkhout, A. J. C., Cowan, N., Crunaire, S., Dammers, E., Ebert, V., Gaudion, V., Haaima, M., Häni, C., John, L., Jones, M. R., Kamps, B., Kentisbeer, J., Kupper, T., Leeson, S. R., Leuenberger, D., Lüttschwager, N. O. B., Makkonen, U., Martin, N. A., Missler, D., Mounsor, D., Neftel, A., Nelson, C., Nemitz, E., Oudwater, R., Pascale, C., Petit, J.-E., Pogany, A., Redon, N., Sintermann, J., Stephens, A., Sutton, M. A., Tang, Y. S., Zijlmans, R., Braban, C. F., and Niederhauser, B.: Intercomparison of in situ measurements of ambient NH3: instrument performance and application under field conditions, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 6755–6787, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-15-6755-2022, 2022.

Van Damme, M., Clarisse, L., Heald, C. L., Hurtmans, D., Ngadi, Y., Clerbaux, C., Dolman, A. J., Erisman, J. W., and Coheur, P. F.: Global distributions, time series and error characterization of atmospheric ammonia (NH3) from IASI satellite observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 2905–2922, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-2905-2014, 2014.

Van Damme, M., Clarisse, L., Whitburn, S., Hadji-Lazaro, J., Hurtmans, D., Clerbaux, C., and Coheur, P.-F.: Industrial and agricultural ammonia point sources exposed, Nature, 564, 99–103, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0747-1, 2018.

Van Damme, M., Clarisse, L., Franco, B., Sutton, M. A., Erisman, J. W., Kruit, R. W., van Zanten, M., Whitburn, S., Hadji-Lazaro, J., Hurtmans, D., Clerbaux, C., and Coheur, P.-F.: Global, regional and national trends of atmospheric ammonia derived from a decadal (2008–2018) satellite record, Environ. Res. Lett., 16, 055017, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd5e0, 2021.

Warner, J. X., Wei, Z., Strow, L. L., Dickerson, R. R., and Nowak, J. B.: The global tropospheric ammonia distribution as seen in the 13-year AIRS measurement record, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 5467–5479, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-5467-2016, 2016.

Warner, J. X., Dickerson, R. R., Wei, Z., Strow, L. L., Wang, Y., and Liang, Q.: Increased atmospheric ammonia over the world's major agricultural areas detected from space, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 2875–2884, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072305, 2017.

Werwein, V., Brunzendorf, J., Li, G., Serdyukov, A., Werhahn, O., and Ebert, V.: High-resolution Fourier transform measurements of line strengths in the 0002-0000 main isotopologue band of nitrous oxide, Appl. Opt., 56, E99–E105, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.56.000E99, 2017

Wyer, K. E., Kelleghan, D. B., Blanes-Vidal, V., Schauberger, G., and Curran, T. P.: Ammonia emissions from agriculture and their contribution to fine particulate matter: A review of implications for human health, J. Environ. Manage., 323, 116285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116285, 2022.

Yang, Y., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Wang, Z., Chen, Y., and He, H.: Impact of high PM2.5 nitrate on visibility in a medium size city of Pearl River Delta, Atmos Pollut. Res., 13, 101592, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2022.101592, 2022.

Yu, O., Sheppard, L., Lumley, T., Koenig, J. Q., and Shapiro, G. G.: Effects of ambient air pollution on symptoms of asthma in Seattle-area children enrolled in the CAMP study, Environ. Health Perspect., 108, 1209–1214, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.001081209, 2000.

Yurchenko, S. N.: A theoretical room-temperature line list for 15NH3, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 152, 28–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2014.10.023, 2015.