the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Forward modeling of spaceborne radar observations

Satya Kalluri

Yanqiu Zhu

Accurate forward models, particularly radiative transfer models, are essential for the assimilation of both passive and active satellite observations in modern data assimilation frameworks. The Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM), widely used in the assimilation of satellite observations within numerical weather prediction systems, especially in the United States, has recently been expanded to include a radar module. This study assesses the new module across multiple radar frequencies using observations from the Earth Clouds, Aerosols and Radiation Explorer Cloud Profiling Radar (EarthCARE CPR), the CloudSat CPR, and the Global Precipitation Measurement Dual-Frequency Precipitation Radar (GPM DPR). Simulated radar reflectivities were compared with the spaceborne measurements to evaluate the impacts of hydrometeor profiles, particle size distributions (PSDs), and frozen hydrometeor habits. The results indicate that both PSD selection and particle shape largely influence the simulated reflectivities, with snow particle habits introducing differences of up to 4 dBZ in W-band comparisons. For the GPM DPR, reflectivities simulated using the Thompson PSD showed closer agreement with the observations than those using the Abel PSD; this agreement should be interpreted in the context of the limited independence between the observations and the retrievals used as input to the CRTM, which themselves rely on PSD-related assumptions. The sensitivity of forward radar simulations to microphysical assumptions, underscores their importance in the assimilation of radar observations in numerical weather forecast models.

- Article

(4850 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Radiative transfer models (RTMs), which simulate how electromagnetic radiation interacts with the atmosphere, serve as critical tools in the field of remote sensing and data assimilation. These models facilitate the interpretation of satellite observations, which is essential for various applications, including weather forecasting, climate monitoring, and environmental assessments (Liou, 2002; Petty, 2006). These models are also widely used to retrieve different products from spaceborne measurements (Saunders et al., 2018; Aumann et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2023). Therefore, the accuracy of these models directly influences the quality of meteorological analyses and predictions, highlighting the need for continuous advancements in radiative transfer methodologies and evaluation of the results (Geer et al., 2017, 2018).

The Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM) is an open-source code that supports both research and operational work in the satellite community. CRTM can simulate a wide range of spectral channels, from visible to microwaves providing a flexible framework for assimilation of observations from spaceborne instruments (Chen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2023). CRTM also provides as a collaborative platform, allowing agencies such as NOAA, NASA, and the DOD, along with academia, to contribute to the development of a shared radiative transfer model.

There is a growing number of current and planned spaceborne radar missions, including the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) (Kummerow et al., 1998), CloudSat Cloud Profiling Radar (CPR) (Stephens et al., 2002), the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) (Hou et al., 2014), the Feng Yun–3G Precipitation Measurement Radar (PMR) (Zhang et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2025), and the Earth Clouds, Aerosols and Radiation Explorer (EarthCare) CPR (Illingworth et al., 2015), as well as planned missions such as the Wind Velocity Radar Nephoscope (WIVERN) (Illingworth et al., 2018) and the INvestigation of Convective UpdraftS (INCUS) (van den Heever et al., 2022).

The radar instruments provide vertical profiles of reflectivity that can be directly related to cloud and precipitation structures that cannot be retrieved from passive sensors. These observations have numerous applications, including evaluating cloud and precipitation simulations in numerical weather prediction (NWP) models, improving our understanding of key atmospheric processes, and assimilation into NWP systems. All of these applications require accurate radiative transfer models (RTMs) to simulate the interaction of radar signals with hydrometeors (Prigent, 2010; Battaglia et al., 2020, 2024; Moradi et al., 2023).

Currently, several NWP centers use active sensor simulators tailored to their own systems for the assimilation of spaceborne radar observations. Di Michele et al. (2012) used the ZmVar forward operator to compare ECMWF forecasts with CloudSat radar data, showing that simulated reflectivities are highly sensitive to assumptions about precipitation fraction, particle size, and hydrometeor properties.

Okamoto et al. (2016) demonstrated that direct assimilation of GPM DPR reflectivity has the capability to improve the forecasts. Using an ensemble-based variational scheme with careful preprocessing (quality control and superobbing), DPR data provided vertically resolved information to better constrain rain mixing ratios and updrafts, while complementing GMI radiance assimilation. Results showed that combined DPR and GMI assimilation outperformed either dataset alone, with DPR helping to mitigate biases such as excessive snow and spurious rain increases.

Fielding and Janisková (2020) explore the direct assimilation of spaceborne radar and lidar observations within the ECMWF 4D-Var system by developing optimized, efficient, and differentiable observation operators tailored for these narrow-footprint active sensors. The work includes the introduction of a fully flow-dependent observation-error characterization. Fielding and Janisková (2020) implement rigorous screening, quality control, and bias-correction procedures to prevent degradation of the analysis.

Recent developments in RTTOV-SCATT have extended its capabilities to simulate active radar observations alongside passive microwave sensors within a consistent radiative transfer framework. The radar simulator introduced in version 13 includes improvements to melting-layer parameterizations, with a revised scheme shown to better reproduce GPM DPR observations, particularly below the freezing level. This enhanced capability can be used in either NWP model evaluation or data assimilation (Geer et al., 2021; Mangla et al., 2025).

The active sensor module in CRTM is integral for assimilating remote sensing observations specifically from spaceborne active instruments such as EarthCARE CPR and GPM DPR (Moradi et al., 2023). This module has been successfully integrated into the Joint Effort for Data assimilation Integration (JEDI) framework, which is currently being integrated into multiple NWP systems across the globe. The evaluation of CRTM's active sensor module, particularly for Ku, Ka, and W bands, will contribute significantly to the readiness of the JEDI system for the assimilation of forthcoming spaceborne observations.

Both forward modeling, i.e., simulating radar reflectivities from input water content profiles, and inverse modeling, i.e., retrieving microphysical properties from radar reflectivity observations, depend on accurate modeling of particle scattering. The scattering properties depend on particle dimension, shape, density, phase, and orientation with respect to the radar wavelength. While the scattering properties of liquid hydrometeors at Ku- and Ka-bands can be accurately computed using the Mie theory (Seto et al., 2021; Liao et al., 2013), W-band simulations, which largely depend on frozen habits, require scattering calculations to be based on more realistic non-spherical shapes. Several schemes have been used in the past to compute the scattering properties of frozen hydrometeors, including T-matrix and Discrete Dipole Approximation (DDA) methods (Eriksson et al., 2018; Liu, 2008; Mishchenko et al., 1999; Kuo et al., 2016; Petty and Huang, 2010; Geer et al., 2021). This study employs the scattering database developed by Eriksson et al. (2018).

Evaluation of radiative transfer models require surface, atmospheric, and hydrometeor profiles. There are three main sources of input profiles for validating RT models: in situ measurements, NWP simulations, and retrievals from combined active–passive sensors. In this study, we use retrieval products to avoid temporal and spatial mismatches between the observations and input profiles. While these retrievals involve radiative transfer assumptions, they still provide a practical and reliable basis for evaluating forward models.

This paper aims to assess the performance of the CRTM active sensor module in simulating radar observations across the Ku, Ka, and W bands using atmospheric and hydrometeor profiles collocated with radar observations. Section 2 provides an overview of the CRTM, Sect. 3 describes the instruments, Sect. 4 presents the results, and Sect. 5 offers the conclusions.

Radiative transfer models are the backbone of data assimilation frameworks used to incorporate satellite observations from both passive and active instruments into NWP models. These models, often refereed to as the forward model or observation operator, simulate satellite measurements based on surface and atmospheric state variables and hydrometeor profiles provided by the NWP models (Zhou et al., 2023; Liang et al., 2023). Modern data assimilation systems predominantly employ four-dimensional variational (4D-Var) methods. 4D-Var aims to optimally estimate the initial conditions by minimizing a cost function that represents the difference between model predictions and observational data over a specified temporal window, thus ensuring a fit between the model trajectory and incoming data in four-dimensional space (three spatial dimensions plus time) (Rabier et al., 2000).

The general formulation of the data assimilation cost function can be expressed as

where J(x) is the cost function to be minimized; y is the vector of observations; ℋ(x) is the (generally nonlinear) observation operator that maps the model state vector x into observation space; xb denotes the background (or prior) state; B is the background error covariance matrix; and R is the observation error covariance matrix (Rabier et al., 2000).

2.1 Community Radiative Transfer Model

The Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM), developed by the Joint Center for Satellite Data Assimilation (JCSDA), is a computationally efficient and flexible framework for simulating satellite observations across passive microwave, infrared, and visible sensors under both clear-sky and cloudy-sky conditions (Johnson et al., 2023). The CRTM capability has been recently extended with the addition of an active sensor module to facilitate the assimilation of spaceborne radar observations (Moradi et al., 2023)

The model relies on pre-computed lookup tables to represent absorption and scattering processes: absorption coefficients are tailored to each instrument, whereas hydrometeor scattering properties are generalized as functions of particle mass, frequency, and temperature. As a result, a unified set of hydrometeor lookup tables can be applied to all sensors operating within the same spectral domain. In particular, both microwave radiometers and radar systems utilize the same hydrometeor scattering databases due to their shared frequency range. Recent developments have introduced Discrete Dipole Approximation (DDA) lookup tables, extending CRTM's applicability to microwave and radar instruments operating from 10 to 800 GHz (Moradi et al., 2022).

To account for multiple scattering, CRTM integrates two advanced solvers: the Advanced Doubling–Adding (ADA) method (Liu and Weng, 2006) and the Successive-Order-of-Interaction (SOI) method (Heidinger et al., 2006). While these solvers are primarily applied to attenuation computations, backscattering effects are treated using the single-scattering approximation. By default, CRTM employs ADA, which is also adopted in the present study.

Full radiative transfer simulations for microwave and radar instruments in CRTM require atmospheric state variables (temperature, water vapor, and pressure) in conjunction with hydrometeor water content profiles, including snow, hail, graupel, cloud ice, cloud liquid water, and rain. In the case of radar observations, these inputs are essential for computing the two primary processes governing radar measurements: volume backscattering and atmospheric attenuation. Although simulations may be performed for an isolated hydrometeor species (e.g., only snow), such an approach neglects the scattering and attenuation contributions from other hydrometeors.

2.2 Radar forward model

The power received by a radar antenna depends on the transmitted power, the target backscattering, and atmospheric attenuation. By normalizing the backscattered signal with the transmitted power, the instrument characteristics are removed, yielding the radar reflectivity factor. Mathematically, the radar equation can be expressed as follows; readers are referred to Petty (2006) for basic definitions.

where λ is the radar wavelength (m), kw is the dielectric factor of liquid water, βb is the volume backscattering coefficient (m−1), and Γ is the two-way transmittance accounting for atmospheric attenuation. The volume backscattering coefficient is scaled with the radar wavelength and dielectric factor to convert it to the equivalent reflectivity factor. The attenuation is computed from the layer extinction coefficient, which accounts for both absorption and scattering by gases and hydrometeors (Moradi et al., 2023). The attenuation-corrected (Z) and attenuated (Za) reflectivity factors are typically expressed in logarithmic units (dBZ) as:

Particle size distributions (PSDs) are used to derive bulk scattering properties from single-particle scattering characteristics. They provide the number density of particles per unit diameter, n(D) in , which is used to calculate the volume backscattering coefficient βb as:

where σb (m2) is the backscattering cross section of a particle with maximum dimension D (m).

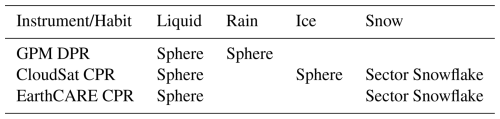

(Thompson et al., 2008)Sato et al. (2018)Austin and Wood (2018)Iguchi et al. (2024)Liao and Meneghini (2022)Seto et al. (2021)Sato et al. (2025)Nakajima et al. (2025)Table 1A comparison of the radar forward-model assumptions employed in the retrieval systems of CloudSat CPR, GPM DPR, and EarthCARE CPR.

In CRTM, βb is expressed using the mass backscattering coefficient kb (m2 kg−1) and the cloud water density ρh (kg m−3):

where ψh (kg m−2) is the layer-integrated cloud water content provided as input to CRTM, and is the slant-path layer thickness, with dz the vertical layer thickness and θ the zenith angle. The coefficient kb is obtained as:

where m(D) is the particle mass (kg), is the particle density, and V(D) is the equivalent spherical volume. For convenience, is used to represent the volume of a sphere with diameter D, even though the actual particles may be nonspherical. This approximation provides a consistent way to relate particle mass and size through an equivalent-volume definition.

The complex permittivity of liquid water, , or equivalently the refractive index , is used to compute the dielectric factor (kw) at a given frequency and a temperature of 273 K:

We used the permittivity models developed by Ellison (2007) for liquid water to ensure consistency with the permittivity model employed in deriving cloud optical properties via the DDA technique Eriksson et al. (2018).

Radar instruments transmit electromagnetic pulses that travel through the atmosphere, interact with hydrometeors, and scatter a portion of the signal back to the antenna. The strength of this backscattered signal, or reflectivity, depends on the scattering properties of the hydrometeors and the attenuation along the signal path (Moradi et al., 2023).

Accurate atmospheric and hydrometeor profiles are essential for evaluating radar forward models using observations from multiple sensors. Three main sources of input profiles are typically considered. In situ measurements are the most accurate when available, but they generally provide only temperature and humidity and lack cloud water information. NWP model output offers complete atmospheric profiles and has been used in data assimilation studies (Fielding and Janisková, 2020; Ikuta, 2016), but the results depend largely on accuracy of the forecast model. In particular, spatial and temporal errors in cloud placement, especially in vertical domain, can lead to large differences between simulated and observed reflectivities.

A third option, and the one used here, is to rely on retrievals from combined active–passive sensors, which provide profiles that are both temporally and spatially matched to the observations being assessed. While this approach is affected by the dependency between the RT model used in the retrievals and the model under evaluation, the CRTM remains independent because it is not used by any of the Level-2 providers considered in this work. Even with this independence in mind, instrument teams invest substantial effort in developing and maintaining the RT components of their retrieval systems, which makes these products a reasonable and useful benchmark for an operational community model like CRTM. Because no single retrieval product can be collocated with observations from all instruments, we therefore used a separate retrieval-based hydrometeor dataset to evaluate the forward model for each instrument considered in this study.

Table 1 summarizes the assumptions used in the forward models within the retrieval systems for each instrument. The notable differences are that only the EarthCARE retrieval assumes non-spherical particles for frozen hydrometeors and also considers multiple scattering in the retrieval system, although both CloudSat CPR and GPM DPR flag cases that may be significantly affected by multiple scattering. These products are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Table 1 also compares the assumptions employed in CRTM with those used in the RT models underlying the retrievals. Note that Field et al. (2007) rescales the PSD from an exponential form at small particle sizes to a gamma distribution at larger sizes. The PSD from Thompson et al. (2008) is the primary distribution used for liquid clouds and rain throughout this study. Additionally, the PSD from Abel and Boutle (2012), which employs an exponential distribution for rain and water, is used for comparison with Thompson et al. (2008), although it is not shown in the table.

3.1 EarthCARE CPR

The European Earth Clouds, Aerosols and Radiation Explorer (EarthCARE) satellite carries four instruments to study the role of clouds and aerosols in Earth's climate (Illingworth et al., 2015). Among these, the Cloud Profiling Radar (CPR) is a Doppler-capable radar that penetrates clouds and light precipitation, providing detailed measurements of vertical structure, particle size, water content, and velocities.

The CPR is equipped with a 2.5 m antenna deployed shortly after launch. CPR operates at 94 GHz and provides a vertical resolution of 500 m. The high sensitivity of the radar ensures the detection of weak microwave backscatter from hydrometeors, while internal calibration modes maintain the linearity and precision of the signal processing system.

In our study, we used cloud-related microphysical parameters derived from the CPR-ATLID synergy cloud algorithm, as described in Okamoto et al. (2024) and Sato et al. (2025). Specifically, we utilized the updated vBb/v1.1 version of the algorithm, which provides cloud masks and cloud type classifications. This version also improves detection near the ground by reducing surface clutter contamination compared to previous versions. The dataset includes Level 2 cloud and precipitation microphysics retrievals from EarthCARE's CPR, ATLID lidar, and multispectral imager.

3.2 GPM DPR

The Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) onboard the NASA-JAXA Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory is a flagship instrument for observing precipitation worldwide. The DPR consists of two co-aligned radars: the Ku-band Precipitation Radar (KuPR) operating at 13.6 GHz and the Ka-band Precipitation Radar (KaPR) at 35.5 GHz. Together, they provide 3-dimensional observations of rainfall and snowfall, enabling accurate estimation of precipitation rates, drop size distributions, and vertical precipitation structure. By comparing differential attenuation between the two frequencies, DPR can distinguish between rain and snow, improving sensitivity to light precipitation and snowfall in mid-latitude regions. The dual-frequency capability enhances the accuracy of hydrological and meteorological analyses, supports numerical weather prediction, and allows scientists to study storm microphysics in unprecedented detail (Hou et al., 2014).

Each radar has a nadir spatial resolution of approximately 5 km with a range resolution of 250 m, covering a swath of up to 245 km. The high sensitivity and advanced calibration techniques of DPR allow it to detect both weak and intense precipitation over land and ocean, day and night, providing vital data for climate research, hydrological studies, and weather forecasting (Hou et al., 2014; Skofronick-Jackson et al., 2017).

For our study, we used precipitation and environmental data from Version 07 of the GPM DPR Precipitation Profile L2A dataset (GPM_2ADPR) (GPM Science Team, 2021; Iguchi et al., 2024). This dataset provides single- and dual-frequency-derived precipitation estimates from the Ku- and Ka-band radars onboard the GPM Core Observatory. The products include precipitation retrieved from the wide-swath Ku-band (245 km), the narrow-swath Ka-band (125 km), and dual-frequency measurements over the narrow swath. For dual-frequency retrievals, the inner swath fields of view of Ku- and Ka-band measurements are co-aligned, allowing derivation of particle size distribution and improved estimation of rainfall rate and equivalent liquid water content (Precipitation Processing System (PPS) At NASA GSFC, 2021; Iguchi et al., 2024).

These DPR retrievals also include environmental profiles assumed in the Level 2 retrieval algorithm, such as atmospheric temperature, pressure, and water vapor. The radar measurements are performed at each range bin along the slant path of the radar instrument field of view (IFOV) (GPM Science Team, 2021).

Iguchi et al. (2024) discusses Multiple Scattering (MS) as an error source in DPR retrievals, particularly at the Ka-band. The retrieval algorithm includes a Trigger module (TRG) which utilizes an experimental method specifically designed to detect and quantify the degree of MS and Non-Uniform Beam Filling effects within a precipitating profile. Although the lower-frequency Ku-band is rarely impacted, the algorithm computes quantitative MS metrics for both bands that can be beneficial for the quality control of the retrievals (Iguchi et al., 2024).

3.3 CloudSat CPR

CloudSat, launched in 2006 into a sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of approximately 700 km, was designed to investigate the role of clouds in the climate system. It carried a CPR, which operates at 94.05 GHz with a bandwidth of 0.3125 MHz, providing radar reflectivities with a vertical resolution of 500 m. CPR measurements are averaged onboard over 0.16 s, yielding a footprint of 1.4 by 1.7 km. These are further averaged during ground processing to an along-track resolution of 3.5 km (Stephens et al., 2002). In this study, we used radar reflectivity from the CloudSat Level 2B-GEOPROF-R05 dataset (Marchand et al., 2008), which ensures significant radar echoes from hydrometeors rather than noise or clutter.

Cloud liquid and ice water content profiles were obtained from the Release 05 Level 2B-CWC-RVOD dataset, derived from CloudSat radar reflectivity and Aqua MODIS cloud optical depth using the algorithm described in (Leinonen et al., 2016). Inputs to this algorithm include CloudSat radar reflectivity (Marchand et al., 2008) and MODIS cloud optical depth onboard Aqua (Platnick et al., 2003). Snow water content was obtained from the Level 2C Snow Profile (2C-SNOW-PROFILE) dataset (Wood and L'Ecuyer, 2018), retrieved using an optimal estimation technique. Due to ground clutter, the base of the retrieved snow layer may be truncated above the surface (Wood and L'Ecuyer, 2018). While graupel is not explicitly retrieved, it is likely encompassed within the ice water content. Moradi et al. (2023) demonstrate that fully swapping the ice water content between ice clouds and graupel can introduce differences of up to 5 dBZ in the heavily convective regions of tropical cyclones, although in most areas the differences are substantially smaller. Hail was not considered in RT simulations due to the absence of hail water content retrievals.

Finally, ERA-Interim atmospheric profiles of temperature, water vapor, and pressure (Dee et al., 2011) were interpolated to CloudSat geolocations and used as input for CRTM. These profiles have been validated against both satellite observations and in-situ radiosonde data (Virman et al., 2021), and are considered sufficiently accurate for calculating gaseous attenuation.

The results are categorized into three sections: first, evaluating the CRTM forward model for the Ku/Ka and W bands; second, investigating how the particle size distribution impacts reflectivity calculations in the Ku/Ka band; and finally, exploring the impact of the shape of the snow particles on reflectivity computations for the W band.

4.1 Evaluation of the forward model

Evaluating a forward radiative transfer model at radar frequencies requires atmospheric variables such as pressure, temperature, and water vapor, in addition to hydrometeor profiles including cloud liquid, ice, rain, and snow water contents. While the DPR frequencies are primarily affected by rain backscatter, the CPR W-band is more sensitive to backscatter from frozen hydrometeors, though backscatter from low-altitude rain can also be important. Although liquid cloud droplets are typically too small to contribute directly to backscatter, they affect the measured reflectivity through attenuation.

As noted earlier, there are several sources that can be used to validate a forward model. For this study, we have employed retrieval products to avoid temporal and spatial mismatches with the observations. While we acknowledge that these retrievals also depend on RT simulations, CRTM is not used in retrieving these products. Therefore, we consider these retrieval products a reliable independent source for validating the CRTM. Table 2 show the habits, including the shape, used in CRTM simulations for each instrument.

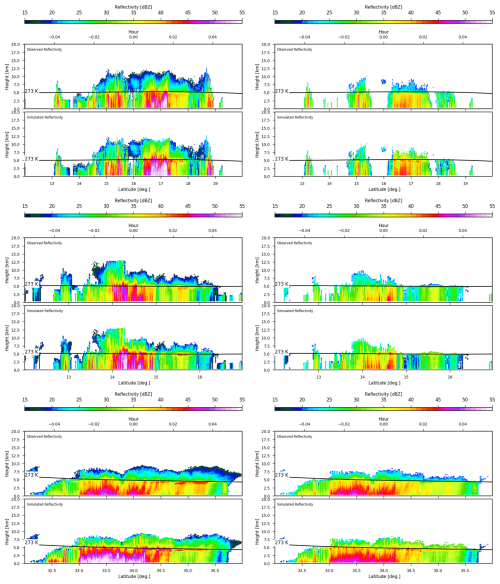

We evaluated the forward model using multiple overpasses from CloudSat CPR and GPM DPR during hurricanes, as well as global observations from EarthCARE CPR. The CloudSat CPR data are from 19 August 2023, with over 160 000 valid observations; the EarthCARE CPR data are from the first week of May 2025, with over 12 million valid observations; and the GPM DPR data are from several days in September 2017, with more than 50 million valid global observations. We screened out any observations below the minimum detectable reflectivity thresholds proposed in the literature for these instruments: 15.46 and 19.18 dBZ for GPM DPR Channels 1 and 2 Liao and Meneghini (2022), −30 dBZ for CloudSat CPR Arulraj and Barros (2017), and −35 dBZ for EarthCARE CPR Wehr et al. (2023).

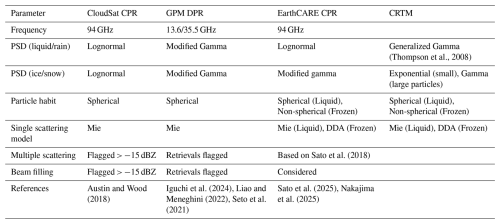

Table 3Statistics of the differences between simulated and observed reflectivities are reported, including the mean, standard deviation (SD), percentiles from the 5th (P5) to the 95th (P95), and the number of observations (nobs). The PSDs for liquid and frozen hydrometeors are also included in the table: F07 indicates Field 2007 PSD, T08 indicates Thompson 2008 PSD, and A12 indicates Abel 2012 PSD. We used sector snowflake to represent snow particles.

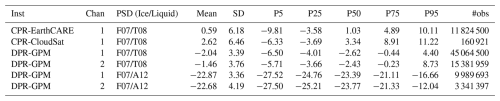

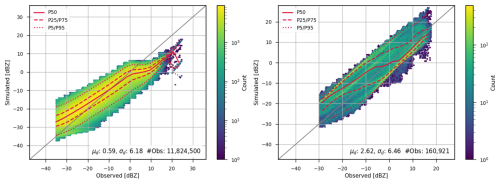

Figure 1Simulated vs. observed CloudSat CPR reflectivities for Hurricane Bill on 19 August 2009, at 17:19 UTC. Simulations include contributions from liquid cloud, ice cloud, and snow water content.

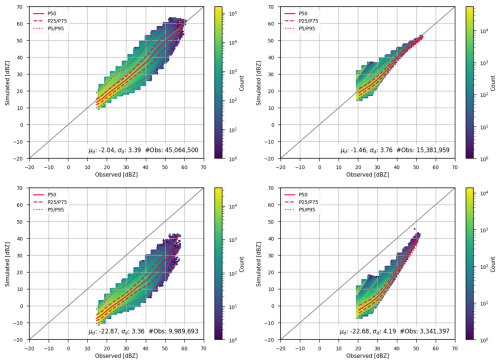

Table 3 summarizes the mean, standard deviation, and selected percentiles of the differences between simulated and observed reflectivities for all three instruments using global observations. The results presented here are based on attenuated reflectivity, unless noted otherwise. The PSDs used in the simulations are summarized in the table. The PSD for frozen hydrometeors follows Field et al. (2007), while those for rain and liquid clouds are based on either Thompson et al. (2008) or Abel and Boutle (2012).

For EarthCARE CPR, the simulated reflectivities are on average slightly higher than observations by 0.59 dB, with a standard deviation of 6.18 dB. The percentile distribution shows that 90 % of the differences are within 10 dB, the median (P50) difference is 1.03 dB, and half of the cases have differences smaller than 5 dB.

CloudSat CPR also shows a positive bias, with simulations exceeding observations on average by 2.62 dB. The spread is similar to EarthCARE, with a standard deviation of 6.46 dB. The median difference is 3.34 dB, and 50 % of the cases have absolute differences below 9.0 dB.

In contrast, GPM DPR shows a negative bias for the Ku-band (channel 1) global data, with an average difference of −2.04 dB and a narrower spread (standard deviation 3.39 dB). The Ka-band (channel 2) global results are closer to neutral, with a mean difference of −1.46 dB and slightly larger variability (SD 3.76 dB). Finally, for the DPR Ku and Ka bands results using the Abel 2012 PSD, the biases are strongly negative at −22.87 and −22.68 dB, respectively, with similar spreads to the results from the Thompson 2008 PSD (3.3–4.2 dB).

Figure 2CPR simulated reflectivities from both EarthCARE (left) and CloudSat (right) compared with observed reflectivities using a global dataset. Multiple percentiles are also plotted, including the 5th (P5), 25th (P25), 50th (P50), 75th (P75), and 95th (P95). The mean (μd) and standard deviation (σd) of the differences, as well as number of observations (#obs) are also displayed on the plots.

Figure 1 shows simulated versus observed attenuated reflectivity values for CloudSat CPR on 19 August 2009, at 17:19:00 UTC. During this time, CloudSat passed over the eye of a tropical cyclone, providing excellent vertical profiling. The input hydrometeor profiles were obtained from a retrieval dataset derived from multiple instruments aboard NASA's A-Train constellation (Leinonen et al., 2016; Wood and L'Ecuyer, 2018). Simulations and observations are shown only for atmospheric layers above the melting level (273 K), since the simulations do not account for rain effects. As shown in Table 2, rain backscatter was excluded from simulations for CloudSat CPTR, because no reliable rain water content was available that was collocated with the CloudSat CPR observations. However, since the CPR 94-GHz radar is primarily sensitive to frozen hydrometeors, excluding rain water content while not ideal, is unlikely to have a substantial impact on the results.

Since no EarthCARE overpasses of tropical cyclones were available during the relatively short period of data coverage, we used simulations from a global dataset to compare with CPR observations from both EarthCARE and CloudSat (Fig. 2). As described in Section 3 and summarized in Table 2, the EarthCARE retrieval dataset does not provide separate water content values for ice and snow particles. Therefore, the EarthCARE simulations include only liquid cloud water and snow, whereas the CloudSat simulations include liquid cloud, ice cloud, and snow water content.

Overall, the simulated reflectivities from both sensors show good agreement with the corresponding observations. The EarthCARE CPR simulations show a smaller mean difference from the observed reflectivities (0.59 dBZ) compared with CloudSat (2.62 dBZ). However, the percentile distributions show that simulations for both sensors tend to overestimate the observations at lower reflectivities (approximately below 0 dBZ). For EarthCARE CPR, the simulations additionally underestimate the observations at reflectivities above 0 dBZ.

Several factors contribute to discrepancies between observed and simulated reflectivities. These include differences in PSDs and particle shape assumptions used in the CRTM calculations compared with the assumption made during retrieving these products from observations, uncertainties in the input profiles, and the exclusion of certain hydrometeor types from the simulations. For CloudSat, rain water content is excluded, but liquid, ice, and snow water contents are included in the forward calculations. The CloudSat retrievals assume lognormal PSDs and spherical Mie scattering. In contrast, our forward model assumes a generalized gamma PSD for liquid cloud particles and the Field (2007) parameterization for frozen hydrometeors, which combines an exponential distribution for small particles with a gamma distribution for larger particles (see Table 1).

EarthCARE simulations include Mie-based spherical liquid cloud particles and sector snowflake habit for frozen hydrometeors; however, unlike the CloudSat simulations, ice water content is not included. Notably, the assumptions made in EarthCARE CPR retrievals are more consistent with the assumptions made in our simulations that use non-spherical DDA-based scattering calculations and a modified gamma PSD for frozen hydrometeors. Therefore, the underestimation of EarthCARE reflectivities at higher reflectivities may therefore be, at least partly, attributed to the exclusion of ice water content in the forward model calculations.

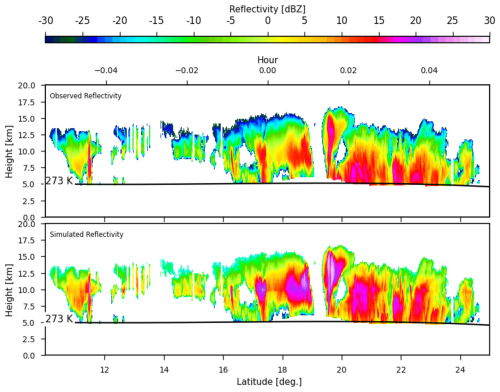

Figure 3Observed vs. simulated GPM DPR reflectivities for Ku (left) and Ka (right) bands during Hurricane Irma (5 September 2017, 16:50 UTC), Hurricane Maria (18 September 2017, 02:01 UTC), and Hurricane Jose (18 September 2017, 03:39 UTC).

Figure 3 shows observed versus simulated GPM DPR reflectivities for three different tropical cyclones from 2017. Unlike CPR, which has a narrow, nadir-viewing beam, the DPR features a wider swath width. As a result, the field of view covering the cyclone's eye was not necessarily located at nadir, and in some cases, DPR did not capture observations directly over the storm center. Consequently, the eye of the cyclone may not be visible in these plots.

DPR observations are primarily sensitive to precipitation and liquid cloud water content, and thus reflectivities exceeding the sensitivity threshold are mostly observed below the melting layer. Across all three cyclones, there is strong agreement between observed and simulated reflectivities. For these simulations, we used CRTM cloud coefficients generated using the Thompson PSD (Thompson et al., 2004, 2008), and included both liquid cloud and rain water content as shown in Table 2.

4.2 Impact of PSD on Ku/Ka

As shown in Eqs. (4) and (6), the particle size distributions are used to compute bulk backscattering coefficients from single-particle scattering properties. Over the years, many PSDs have been developed, typically tailored to individual hydrometeor types such as rain or snow. PSDs may be defined using single- or double-moment schemes and often require input parameters such as effective radius or water content. The bulk scattering databses used in fast radiative transfer models are generally parameterized based on the input required by PSD (water content or effective radius), frequency, and temperature.

Figure 4Impact of PSD on simulated GPM DPR reflectivities using a global dataset: comparison between Thompson et al. (2004) PSD (top) and Abel and Boutle (2012) PSD (bottom). The left panels show the KuPR channel, and the right panels show the KaPR channel. The 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles are also shown to indicate how the data are distributed. The mean (μd) and standard deviation (σd) of the differences, as well as number of observations (#obs) are also displayed on the plots.

Figure 4 shows GPM DPR observations compared with simulations conducted using either Abel (Abel and Boutle, 2012) or Thompson (Thompson et al., 2008, 2004) PSDs. Simulations based on the Abel and Boutle (2012) PSD systematically underestimate observed reflectivities, showing a consistent bias of more than 22 dBZ. These simulations rarely exceed 40 dBZ, whereas observations reach up to 60 dBZ. In contrast, simulations using Thompson et al. (2004) PSD show much better agreement with observations, both in magnitude, reaching reflectivities up to 60 dBZ, and in reduced systematic bias.

In the case of simulations based on Thompson et al. (2004) PSD, the agreement is notably strong. In both bands, the 25th and 75th percentiles are very close to the median (50th percentile), showing that half of the data have a difference close to the median. The retrieval database used to prepare the input water content profiles required by CRTM did not include water content for frozen hydrometeors such as snow and ice, see Table 2. As a result, these simulations do not account for frozen hydrometeors, which may contribute additional reflectivity in certain cases and could explain some of the residual discrepancies. However, because DPR frequencies are primarily sensitive to rain and liquid cloud, excluding frozen hydrometeor water content, while potentially affecting specific situations such as heavy snow, is unlikely to have a large impact on the overall results.

The PSD by Abel and Boutle (2012) is based on an exponential distribution, while both PSDs used in GPM DPR retrievals and Thompson PSD are based on the Gamma distribution. This difference in the assumed PSD shape may explain some of the discrepancies between simulations using the Abel PSD and observations. However, the magnitude of the difference suggests that the root cause is likely more than just the choice of size distribution alone, potentially indicating a fundamental deficiency in the PSD formulation by Abel and Boutle (2012).

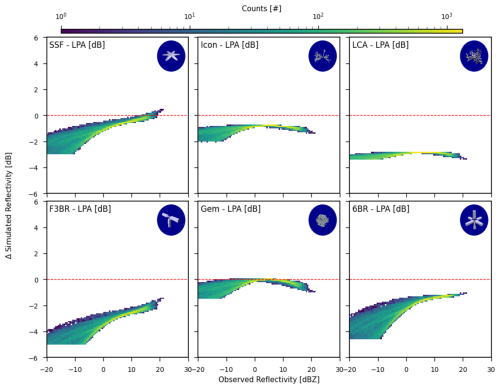

4.3 Impact of Cloud Type on W-band

This section explores the sensitivity of the EarthCARE W-band to various particle shapes for snow water content. The CRTM includes an extensive scattering database for snow and other frozen hydrometeors (Moradi et al., 2022), which we utilized to evaluate the impact of different snow hydrometeor shapes on simulated reflectivity. However, the CRTM cloud scattering database includes only spherical particles for rain; therefore, we have limited this sensitivity study to the W-band, as DPR frequencies are primarily sensitive to rain.

Figure 5Impact of snow hydrometeor shape on simulated radar reflectivity. Values indicate the difference between simulations using each particle shape and those using the LPA habit.

Figure 5 illustrates the sensitivity of CPR W-band to various shapes used to define scattering based on snow water content. Since attenuation can be influenced by several hydrometeor types as well as water vapor, we focus here on attenuation corrected reflectivity to isolate the effects of particle shape.

Figure 5 shows the differences in W-band reflectivity computed using various frozen hydrometeor habits: large plate aggregate (LPA), sector snowflake (SSF), flat three-bullet rosette (F3BR), icon snow (Icon), gem snow (Gem), large column aggregate (LCA), and six-bullet rosette (6BR). LPA is used as the reference habit, as it generally produces the highest reflectivity values, making it easier to interpret differences relative to it.

Overall, the differences between reflectivities are more pronounced at lower reflectivity values. The smallest differences are seen between LPA and Gem snow, followed by LPA and SSF. For F3BR, the difference compared to LPA is about −4 dBZ at lower reflectivities, decreasing to approximately −2 dBZ for higher reflectivity values. The difference between LPA and LCA remains around 4 dBZ, while Icon snow and 6BR differ by approximately 2 dBZ relative to LPA. It should be noted that when these differences are converted to physical units, such as mm6 m−3, the absolute differences become much larger at higher reflectivity values. For instance, at −30 dBZ with a 4 dBZ difference, the difference in linear units is approximately 1.51 × 10−3 mm6 m−3, whereas at 30 dBZ with a 1 dBZ difference, it is approximately 2.59 × 102 mm6 m−3.

Previous studies by Geer and Baordo (2014) and Moradi et al. (2022) have demonstrated that it is possible to identify the optimal particle shape that produces the best agreement with observations for a specific NWP system. While it is not practically feasible to determine the exact hydrometeor shape present in each model grid box, and in reality, multiple shapes may coexist, this analysis can guide the selection of the most compatible particle shape for a given NWP model.

In this study, we evaluated the performance of a radiative transfer model across multiple radar frequencies using observations from EarthCARE CPR, GPM DPR, and CloudSat CPR. The analysis focused on both the sensitivity of different frequencies to hydrometeor types and the impact of PSDs and hydrometeor shape assumptions on simulated radar reflectivities.

Our results demonstrate that forward simulations using well-characterized PSDs and hydrometeor profiles can reproduce observed reflectivities with good accuracy, particularly when using retrievals aligned with radar measurements.

We showed that different snow particle habits introduce systematic differences in simulated reflectivities, with the choice of hydrometeor shape affecting the agreement with observed W-band data by several dBZ. These findings support the idea that radiative transfer model accuracy is highly dependent on appropriate microphysical assumptions, particularly for high-frequency radar bands.

Similarly, GPM DPR simulations were shown to be highly sensitive to the choice of PSD, with the Thompson PSD (Thompson et al., 2004, 2008) producing reflectivity magnitudes more consistent with observations than the Abel PSD (Abel and Boutle, 2012). However, this apparent consistency should be interpreted cautiously, since the retrievals used as input to the CRTM are not fully independent of the observations and themselves rely on underlying PSD assumptions. As a result, these findings may reflect greater consistency with the assumptions employed during the retrieval process rather than definitive evidence of deficiencies in any particular PSD, which would require independent evaluation using in situ measurements.

Future work will include expanding the analysis to cover more hydrometeor types (e.g., hail, graupel), and also determining observation errors for the assimilation of spacebrone radar observations in the NWP models.

The Community Radiative Transfer Model is available from the Joint Center for Satellite Data Assimilation GitHub repository https://github.com/JCSDA/CRTMv3 (last access: 10 September 2025; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13376762, Johnson et al., 2024). EarthCare CPR data can be accessed through the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency at https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/EARTHCARE/index.html (last access: 10 September 2025). CloudSat CPR data are provided by Colorado State University's dedicated repository https://www.cloudsat.cira.colostate.edu/ (last access: 10 September 2025), and GPM DPR data are available from NASA at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/ (last access: 10 September 2025).

I.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. S.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. Y.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Early results from EarthCARE (AMT/ACP/GMD inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

We sincerely appreciate the reviewers' thoughtful and constructive feedback. Their insights were genuinely helpful and contributed meaningfully to improving the clarity and overall quality of the manuscript.

This research has been supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grant no. 80NSSC21K1361) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (grant no. NA24NESX432C0001, Cooperative Institute for Satellite Earth System Studies, CISESS) at the University of Maryland/ESSIC.

This paper was edited by Maximilian Maahn and reviewed by Alan Geer and one anonymous referee.

Abel, S. J. and Boutle, I. A.: An improved representation of the raindrop size distribution for single-moment microphysics schemes, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 138, 2151–2162, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.1949, 2012. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Arulraj, M. and Barros, A. P.: Shallow Precipitation Detection and Classification Using Multifrequency Radar Observations and Model Simulations, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 34, 1963–1983, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-17-0060.1, 2017. a

Aumann, H. H., Chen, X., Fishbein, E., Geer, A., Havemann, S., Huang, X., Liu, X., Liuzzi, G., DeSouza-Machado, S., Manning, E. M., Masiello, G., Matricardi, M., Moradi, I., Natraj, V., Serio, C., Strow, L., Vidot, J., Chris Wilson, R., Wu, W., Yang, Q., and Yung, Y. L.: Evaluation of Radiative Transfer Models With Clouds, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 123, 6142–6157, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JD028063, 2018. a

Austin, R. T. and Wood, N. B.: Level 2B Radar-only Cloud Water Content (2B-CWC-RO) Process Description and Interface Control Document, Product Version P1 R05, Technical Report revision 0., NASA JPL CloudSat Project Document, https://www.cloudsat.cira.colostate.edu/cloudsat-static/info/dl/2b-cwc-ro/2B-CWC-RO_PDICD.P1_R05.rev0_.pdf (last access: 10 September 2025), 2018. a

Battaglia, A., Simmer, C., Crewell, S., Czekala, H., Emde, C., Marzano, F., Mishchenko, M. I., Pardo, J. R., and Prigent, C. R.: Emission and scattering by clouds and precipitation, Chap. 3, in: Thermal Microwave Radiation: Applications for remote sensing, 101–224, https://doi.org/10.1049/PBEW052E_ch3, 2024. a

Battaglia, A., Kollias, P., Dhillon, R., Roy, R., Tanelli, S., Lamer, K., Grecu, M., Lebsock, M., Watters, D., Mroz, K., Heymsfield, G., Li, L., and Furukawa, K.: Spaceborne cloud and precipitation radars: Status, challenges, and ways forward, Reviews of Geophysics, 58, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019RG000686, 2020. a

Chen, Y., Han, Y., Liu, Q., Van Delst, P., and Weng, F.: Community Radiative Transfer Model for Stratospheric Sounding Unit, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 28, 1489–1503, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010jtecha1509.1, 2011. a

Dee, D. P., Uppala, S. M., Simmons, A. J., Berrisford, P., Poli, P., Kobayashi, S., Andrae, U., Balmaseda, M. A., Balsamo, G., Bauer, P., Bechtold, P., Beljaars, A. C. M., van de Berg, L., Bidlot, J., Bormann, N., Delsol, C., Dragani, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A. J., Haimberger, L., Healy, S. B., Hersbach, H., Hólm, E. V., Isaksen, L., Kållberg, P., Köhler, M., Matricardi, M., McNally, A. P., Monge-Sanz, B. M., Morcrette, J.-J., Park, B.-K., Peubey, C., de Rosnay, P., Tavolato, C., Thépaut, J.-N., and Vitart, F.: The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 137, 553–597, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.828, 2011. a

Di Michele, S., Ahlgrimm, M., Forbes, R., Kulie, M., Bennartz, R., Janisková, M., and Bauer, P.: Interpreting an evaluation of the ECMWF global model with CloudSat observations: ambiguities due to radar reflectivity forward operator uncertainties, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 138, 2047–2065, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.1936, 2012. a

Ellison, W. J.: Permittivity of Pure Water, at Standard Atmospheric Pressure, over the Frequency Range 0–25THz and the Temperature Range 0–100 °C, Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 36, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2360986, 2007. a

Eriksson, P., Ekelund, R., Mendrok, J., Brath, M., Lemke, O., and Buehler, S. A.: A general database of hydrometeor single scattering properties at microwave and sub-millimetre wavelengths, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 10, 1301–1326, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-1301-2018, 2018. a, b, c

Field, P. R., Heymsfield, A. J., and Bansemer, A.: Snow Size Distribution Parameterization for Midlatitude and Tropical Ice Clouds, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 64, 4346–4365, https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JAS2344.1, 2007. a, b

Fielding, M. D. and Janisková, M.: Direct 4D-Var assimilation of space-borne cloud radar reflectivity and lidar backscatter. Part I: Observation operator and implementation, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 146, 3877–3899, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3878, 2020. a, b, c

Geer, A. J. and Baordo, F.: Improved scattering radiative transfer for frozen hydrometeors at microwave frequencies, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 1839–1860, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-1839-2014, 2014. a

Geer, A. J., Baordo, F., Bormann, N., Chambon, P., English, S. J., Kazumori, M., Lawrence, H., Lean, P., Lonitz, K., and Lupu, C.: The growing impact of satellite observations sensitive to humidity, cloud and precipitation, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 143, 1236–1245, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3172, 2017. a

Geer, A. J., Lonitz, K., Weston, P., Kazumori, M., Okamoto, K., Zhu, Y., Liu, E. H., Collard, A., Bell, W., Migliorini, S., Chambon, P., Fourrié, N., Kim, M.-J., Köpken-Watts, C., and Schraff, C.: All-sky satellite data assimilation at operational weather forecasting centres, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 144, 1191–1217, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3202, 2018. a

Geer, A. J., Bauer, P., Lonitz, K., Barlakas, V., Eriksson, P., Mendrok, J., Doherty, A., Hocking, J., and Chambon, P.: Bulk hydrometeor optical properties for microwave and sub-millimetre radiative transfer in RTTOV-SCATT v13.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 14, 7497–7526, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-7497-2021, 2021. a, b

GPM Science Team: GPM DPR L2A Environment 1.5 hours 5 km V07, Digital Science Data, NASA Goddard Earth Science Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC), https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datacollection/GPM_2ADPRENV_07.html (last access: 10 September 2025), 2021. a, b

Heidinger, A. K., O'Dell, C., Bennartz, R., and Greenwald, T.: The Successive-Order-of-Interaction Radiative Transfer Model. Part I: Model Development, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 45, 1388–1402, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAM2387.1, 2006. a

Hou, A. Y., Kakar, R. K., Neeck, S., Azarbarzin, A. A., Kummerow, C. D., Kojima, M., Oki, R., Nakamura, K., and Iguchi, T.: The Global Precipitation Measurement Mission, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 95, 701–722, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00164.1, 2014. a, b, c

Iguchi, T., Seto, S., Meneghini, R., Yoshida, N., Awaka, J., Le, M., Chandrasekar, V., Brodzik, S., Tanelli, S., Kanemaru, K., Masaki, T., Kubota, T., and Takahashi, N.: GPM/DPR Level-2 Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, Tech. rep., Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), revised July 2024, https://gpm.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/ATBD_DPR_L2.pdf (last access: 10 September 2025), 2024. a, b, c, d, e

Ikuta, Y.: Data assimilation using GPM/DPR at JMA, CAS/JSC WGNE Research Activities in Atmospheric and Oceanic Modelling, Japan Meteorological Society, Kobe, Japan, 46, 01.11–01.12, 2016. a

Illingworth, A. J., Barker, H. W., Beljaars, A., Ceccaldi, M., Chepfer, H., Clerbaux, N., Cole, J., Delano, J., Domenech, C., Donovan, D. P., Fukuda, S., Hirakata, M., Hogan, R. J., Huenerbein, A., Kollias, P., Kubota, T., Nakajima, T., Nakajima, T. Y., Nishizawa, T., Ohno, Y., Okamoto, H., Oki, R., Sato, K., Satoh, M., Shephard, M. W., Velázquez-Blázquez, A., Wandinger, U., Wehr, T., and van Zadelhoff, G.-J.: The EarthCARE Satellite: The Next Step Forward in Global Measurements of Clouds, Aerosols, Precipitation, and Radiation, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 96, 1311–1332, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00227.1, 2015. a, b

Illingworth, A. J., Battaglia, A., Bradford, J., Forsythe, M., Joe, P., Kollias, P., Lean, K., Lori, M., Mahfouf, J.-F., Melo, S., Midthassel, R., Munro, Y., Nicol, J., Potthast, R., Rennie, M., Stein, T. H. M., Tanelli, S., Tridon, F., Walden, C. J., and Wolde, M.: WIVERN: A New Satellite Concept to Provide Global In-Cloud Winds, Precipitation, and Cloud Properties, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 99, 1669–1687, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0047.1, 2018. a

Johnson, B., Dang, C., Moradi, I., gthompsnWRF, StegmannJCSDA, Honeyager, R., Diniz, F. L. R., Barré, J., Ruston, B., Heinzeller, D., Hebert, F., and Vandenberghe, F.: JCSDA/CRTMv3: v3.1.0-zenodo, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13376762, 2024. a

Johnson, B. T., Dang, C., Stegmann, P., Liu, Q., Moradi, I., and Auligne, T.: The Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM): Community-Focused Collaborative Model Development Accelerating Research to Operations, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 104, E1817 – E1830, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-22-0015.1, 2023. a, b, c

Kummerow, C., Barnes, W., Kozu, T., Shiue, J., and Simpson, J.: The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) Sensor Package, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 15, 809–817, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0426(1998)015<0809:TTRMMT>2.0.CO;2, 1998. a

Kuo, K.-S., Olson, W. S., Johnson, B. T., Grecu, M., Tian, L., Clune, T. L., van Aartsen, B. H., Heymsfield, A. J., Liao, L., and Meneghini, R.: The Microwave Radiative Properties of Falling Snow Derived from Nonspherical Ice Particle Models. Part I: An Extensive Database of Simulated Pristine Crystals and Aggregate Particles, and Their Scattering Properties, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 55, 691–708, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-15-0130.1, 2016. a

Leinonen, J., Lebsock, M. D., Stephens, G. L., and Suzuki, K.: Improved Retrieval of Cloud Liquid Water from CloudSat and MODIS, Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 55, 1831–1844, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-16-0077.1, 2016. a, b

Liang, J., Terasaki, K., and Miyoshi, T.: A Machine Learning Approach to the Observation Operator for Satellite Radiance Data Assimilation, Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, Ser. II, 101, 79–95, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2023-005, 2023. a

Liao, L. and Meneghini, R.: GPM DPR Retrievals: Algorithm, Evaluation, and Validation, Remote Sensing, 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14040843, 2022. a, b

Liao, L., Meneghini, R., Nowell, H. K., and Liu, G.: Scattering Computations of Snow Aggregates From Simple Geometrical Particle Models, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 6, 1409–1417, 2013. a

Liou, K. N.: An Introduction to Atmospheric Radiation, 2nd edn., Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-451451-5, 2002. a

Liu, G.: A Database of Microwave Single-Scattering Properties for Nonspherical Ice Particles, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 89, 1563–1570, https://doi.org/10.1175/2008BAMS2486.1, 2008. a

Liu, Q. and Weng, F.: Advanced Doubling–Adding Method for Radiative Transfer in Planetary Atmospheres, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 63, 3459–3465, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS3808.1, 2006. a

Mangla, R., Borderies, M., Chambon, P., Geer, A., and Hocking, J.: Assessment and application of melting-layer simulations for spaceborne radars within the RTTOV-SCATT v13.1 model, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 18, 2751–2779, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-18-2751-2025, 2025. a

Marchand, R., Mace, G. G., Ackerman, T., and Stephens, G.: Hydrometeor detection using CloudSat – an earth-orbiting 94-GHz cloud radar, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 25, 519–533, https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JTECHA1006.1, 00180, 2008. a, b

Mishchenko, M. I., Hovenier, J. W., and Travis, L. D. (Eds.): Light scattering by nonspherical particles: theory, measurements, and applications, 1st edn., Academic Press, San Diego, ISBN 978-0-12-498660-2, 1999. a

Moradi, I., Stegmann, P., Johnson, B., Barlakas, V., Eriksson, P., Geer, A., Gelaro, R., Kalluri, S., Kleist, D., Liu, Q., and Mccarty, W.: Implementation of a Discrete Dipole Approximation Scattering Database Into Community Radiative Transfer Model, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 127, e2022JD036957, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JD036957, 2022. a, b, c

Moradi, I., Johnson, B., Stegmann, P., Holdaway, D., Heymsfield, G., Gelaro, R., and McCarty, W.: Developing a Radar Signal Simulator for the Community Radiative Transfer Model, IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 61, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3330067, 2023. a, b, c, d, e, f

Nakajima, T., Kikuchi, M., Ohno, Y., Okamoto, H., Nishizawa, T., Nakajima, T., Suzuki, K., and Satoh, M.: EarthCARE JAXA Level 2 Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document (L2 ATBD), Tech. rep., Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), Earth Observation Research Center, https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/EARTHCARE/document/reference/dev/EarthCARE_L2_ATBD.pdf (last access: 10 September 2025), 2025. a

Okamoto, H., Sato, K., Nishizawa, T., Jin, Y., Ogawa, S., Ishimoto, H., Hagihara, Y., Oikawa, E., Kikuchi, M., Satoh, M., and Roh, W.: Cloud masks and cloud type classification using EarthCARE CPR and ATLID, Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2024-103, 2024. a

Okamoto, K., Aonashi, K., Kubota, T., and Tashima, T.: Experimental Assimilation of the GPM Core Observatory DPR Reflectivity Profiles for Typhoon Halong (2014), Monthly Weather Review, 144, 2307–2326, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-15-0399.1, 2016. a

Petty, G. W.: A First Course in Atmospheric Radiation, Sundog Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9729033-1-8, 2006. a, b

Petty, G. W. and Huang, W.: Microwave Backscatter and Extinction by Soft Ice Spheres and Complex Snow Aggregates, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 67, 769–787, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JAS3146.1, 2010. a

Platnick, S., King, M., Ackerman, S., Menzel, W., Baum, B., Riedi, J., and Frey, R.: The MODIS cloud products: algorithms and examples from Terra, IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 41, 459–473, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2002.808301, 2003. a

Precipitation Processing System (PPS) At NASA GSFC: GPM DPR Precipitation Profile L2A 1.5 hours 5 km V07, NASA Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center, https://doi.org/10.5067/GPM/DPR/GPM/2A/07, 2021. a

Prigent, C.: Precipitation retrieval from space: An overview, Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 342, 380–389, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crte.2010.01.004, 2010. a

Rabier, F., Järvinen, H., Klinker, E., Mahfouf, J.-F., and Simmons, A.: The ECMWF operational implementation of four-dimensional variational assimilation.i: experimental results with simplified physics, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 126, 1143–1170, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49712656415, 00570, 2000. a, b

Sato, K., Okamoto, H., and Ishimoto, H.: Physical model for multiple scattered space-borne lidar returns from clouds, Opt. Express, 26, A301–A319, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.00A301, 2018. a

Sato, K., Okamoto, H., Nishizawa, T., Jin, Y., Nakajima, T. Y., Wang, M., Satoh, M., Roh, W., Ishimoto, H., and Kudo, R.: JAXA Level 2 cloud and precipitation microphysics retrievals based on EarthCARE radar, lidar, and imager: the CPR_CLP, AC_CLP, and ACM_CLP products, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 18, 1325–1338, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-18-1325-2025, 2025. a, b

Saunders, R., Hocking, J., Turner, E., Rayer, P., Rundle, D., Brunel, P., Vidot, J., Roquet, P., Matricardi, M., Geer, A., Bormann, N., and Lupu, C.: An update on the RTTOV fast radiative transfer model (currently at version 12), Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 2717–2737, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-2717-2018, 2018. a

Seto, S., Iguchi, T., Meneghini, R., Awaka, J., Kubota, T., Masaki, T., And Takahashi, N.: The Precipitation Rate Retrieval Algorithms for the GPM Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar, Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, Ser. II, 99, 205–237, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2021-011, 2021. a, b

Skofronick-Jackson, G., Petersen, W. A., Berg, W., Kidd, C., Stocker, E. F., Kirschbaum, D. B., Kakar, R., Braun, S. A., Huffman, G. J., Iguchi, T., Kirstetter, P. E., Kummerow, C., Meneghini, R., Oki, R., Olson, W. S., Takayabu, Y. N., Furukawa, K., and Wilheit, T.: The Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Mission for Science and Society, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 98, 1679–1695, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00306.1, 2017. a

Stephens, G. L., Vane, D. G., Boain, R. J., Mace, G. G., Sassen, K., Wang, Z., Illingworth, A. J., O'connor, E. J., Rossow, W. B., Durden, S. L., Miller, S. D., Austin, R. T., Benedetti, A., and Mitrescu, C.: The CloudSat mission and the A-Train: A Nw Dimension of Space-Based Observations of Clouds and Precipitation, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 83, 1771–1790, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-83-12-1771, 2002. a, b

Thompson, G., Rasmussen, R. M., and Manning, K.: Explicit Forecasts of Winter Precipitation Using an Improved Bulk Microphysics Scheme. Part I: Description and Sensitivity Analysis, Monthly Weather Review, 132, 519–542, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2004)132<0519:EFOWPU>2.0.CO;2, 2004. a, b, c, d, e, f

Thompson, G., Field, P. R., Rasmussen, R. M., and Hall, W. D.: Explicit forecasts of winter precipitation using an improved bulk microphysics scheme. part II: implementation of a new snow parameterization, Monthly Weather Review, 136, 5095–5115, https://doi.org/10.1175/2008MWR2387.1, 00262, 2008. a, b, c, d, e, f, g

van den Heever, S., Haddad, Z., Tanelli, S., Stephens, G., Posselt, D., Kim, Y., Brown, S., Braun, S., Grant, L., Kollias, P., Luo, Z. J., Mace, G., Marinescu, P., Padmanabhan, S., Partain, P., Petersent, W., Prasanth, S., Rasmussen, K., Reising, S., and Schumacher, C.: The INCUS Mission, in: EGU22, the 24th EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria and Online, presented at the EGU General Assembly 2022, pp. EGU22–9021, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu22-9021, 2022. a

Virman, M., Bister, M., Räisänen, J., Sinclair, V. A., and Järvinen, H.: Radiosonde comparison of ERA5 and ERA-Interim reanalysis datasets over tropical oceans, Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography, 73, 1929752, https://doi.org/10.1080/16000870.2021.1929752, 2021. a

Wehr, T., Kubota, T., Tzeremes, G., Wallace, K., Nakatsuka, H., Ohno, Y., Koopman, R., Rusli, S., Kikuchi, M., Eisinger, M., Tanaka, T., Taga, M., Deghaye, P., Tomita, E., and Bernaerts, D.: The EarthCARE mission – science and system overview, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 16, 3581–3608, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-16-3581-2023, 2023. a

Wood, N. B. and L'Ecuyer, T. S.: Level 2C Snow Profile Process Description and Interface Control Document, Product Version P1 R05, Tech. Rep. P1 R05, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, https://www.cloudsat.cira.colostate.edu/cloudsat-static/info/dl/2c-snow-profile/2C-SNOW-PROFILE_PDICD.P1_R05.rev0_.pdf (last access: 10 September 2025), 2018. a, b, c

Wu, Z., Han, W., Xie, H., Ye, M., and Gu, J.: Assimilation of FY-3G Ku-band radar observations with 1D Bayesian retrieval and 3DVAR in CMA-MESO, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 151, e4964, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4964, 2025. a

Zhang, P., Gu, S., Chen, L., Shang, J., Lin, M., Zhu, A., Yin, H., Wu, Q., Shou, Y., Sun, F., Xu, H., Yang, G., Wang, H., Li, L., Zhang, H., Chen, S., and Lu, N.: FY-3G Satellite Instruments and Precipitation Products: First Report of China's Fengyun Rainfall Mission In-Orbit, Journal of Remote Sensing, 3, 0097, https://doi.org/10.34133/remotesensing.0097, 2023. a

Zhou, L., Lei, L., Tan, Z.-M., Zhang, Y., and Di, D.: Impacts of Observation Forward Operator on Infrared Radiance Data Assimilation with Fine Model Resolutions, Monthly Weather Review, 151, 163–173, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-22-0084.1, 2023. a