the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

A helicopter-based mass balance approach for quantifying methane emissions from industrial activities, applied for coal mine ventilation shafts in Poland

Michael Lichtenstern

Falk Pätzold

Lutz Bretschneider

Andreas Schlerf

Sven Bollmann

Astrid Lampert

Jarosław Nęcki

Paweł Jagoda

Justyna Swolkień

Dominika Pasternak

Robert A. Field

Anke Roiger

This study introduces a helicopter-borne mass balance approach, utilizing the HELiPOD platform, to accurately quantify methane (CH4) emissions from coal mining activities. Compared to conventional research aircraft, the use of an external sling load configuration eliminates the need for aeronautical certifications, facilitates easier modifications and enables local helicopter companies to conduct flights. Furthermore, it allows for plume probing as close as several hundred meters downwind of an emission source and offers comprehensive vertical coverage from 50 m to 3 km altitude, making the HELiPOD an ideal tool to distinguish, capture, and quantify emissions from single sources in complex emission landscapes worldwide. Our approach serves as an independent emission verification tool, bridging the gap between ground-based, drone, near-field and far-field airborne measurements and supports identification of CH4 emission mitigation opportunities. Nineteen mission flights were conducted in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin of Southern Poland in June and October 2022 that targeted CH4 emissions from multiple coal mine ventilation shafts and several drainage stations. The comparison of top-down HELiPOD mass flux estimates against those calculated from bottom-up in-mine CH4 safety sensor and air flow measurements revealed very good agreement with relative deviations of 0 % to 25 %. This indicates, notwithstanding associated uncertainties, that the two independent approaches are capable of estimating CH4 emissions from coal mine ventilation shafts accurately. However, the accuracy and representativeness of derived in-mine data is application-specific and should be evaluated by independent measurements.

With measured CH4 emission rates up to 3000 kg h−1 from individual coal mine ventilation shafts we confirm prior research, while revealing that emission strengths from drainage stations can be of comparable magnitude and should be investigated further. The possibility to detect emissions at rates as low as 20 kg h−1 with the HELiPOD was demonstrated through a controlled release experiment. This emphasises the wide range of potential applications in quantifying sources within a wide range of CH4 emission rates, i.e. from relatively small sources, e.g. biodigesters, landfills, cattle feedlots and manure pits to larger industrial sources including those from the coal, oil and gas sectors.

- Article

(5495 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2830 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Here we present a helicopter-borne mass balance approach focusing on methane (CH4) emissions from coal mining activities in Poland. The deployment of the exceptionally versatile measurement platform HELiPOD (Pätzold et al., 2023) with state-of-the-art mass balance analysis (Cambaliza et al., 2014; Conley et al., 2017; Heimburger et al., 2017; Hajny et al., 2023) is a new methodological approach for estimating CH4 fluxes. More recently, this application has been deployed in studies on other anthropogenic sources as from the oil, gas and waste sectors (Huntrieser et al., 2023a, b).

The importance of reducing CH4 emissions to mitigate the future impacts of climate change is well known (Kirschke et al., 2013; Saunois et al., 2020; Forster et al., 2021). The largest mitigation potentials are predicted for the energy and waste sectors. Eliminating venting, reducing flaring and unintended leakages by introducing new technologies, monitoring and repairing of existing equipment are effective within the oil and gas (O&G) sector (Nisbet et al., 2020). Using fugitive CH4 emissions as an energy source, the oxidation of ventilation air methane (VAM) and pre-mine degasification (gas removal, see e.g. Thakur, 2014) are identified as critical actions for the coal sector (Karacan et al., 2024). Anaerobic digestion with gas recovery and full source separation/recycling of waste have been shown to reduce emissions from waste management. If combined, such efforts could lead to a reduction of the total radiative forcing by 13 % until the end of this century (Höglund-Isaksson, 2012; Harmsen et al., 2020; Höglund-Isaksson et al., 2020; Nisbet et al., 2020; Shindell et al., 2024).

International efforts are brought together through the Global Methane Pledge (GMP) (https://www.globalmethanepledge.org, last access: 3 June 2025) with the shared goal to reduce global CH4 emissions by at least 30 % from 2020 levels until 2030. As of January 2025, 159 countries have joined, representing slightly over 50 % of all global anthropogenic CH4 emissions. This figure would rise substantially if coal producing countries, e.g. China, India, Russia and South Africa, which in sum account for approximately a third of the global anthropogenic CH4 (JRC et al., 2024), sign the GMP. In 2023, China announced the Methane Emissions Control Action Plan that aims to scientifically and cooperatively manage and control CH4 emissions (China's Ministry of Ecology and Environment, 2023). This act is signalling recognition of the importance of mitigation from a country estimated to have the greatest potential for reduction of CH4 emissions.

To support mitigation efforts related to the GMP and to track progress over time (UNEP, 2024), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) collects, synthesises and shares actionable CH4 data through its International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO, 2024). Through CH4 science studies (e.g. Gorchov Negron et al., 2020; Neininger et al., 2021; Korbeń et al., 2022; Naus et al., 2023; Pühl et al., 2024; UNEP, 2024), sharing satellite data via the Methane Alert and Response System (MARS), with the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (OGMP 2.0) and from national emission inventory reporting (e.g. through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC) IMEO supports the production of accurate actionable data to help drive mitigation of emissions. The goal of the science studies is to reconcile the often discrepant bottom-up (company estimates based on emission factors, inventories and ground-based measurements) and top-down (drone, air- and spaceborne measurements) emission estimates and to improve the understanding of the uncertainties of different CH4 source quantification approaches (Höglund-Isaksson, 2017; Vaughn et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2022; Riddick et al., 2024). With a better knowledge of emission magnitudes and associated uncertainties, more efficient mitigation strategies can be developed.

Top-down CH4 mass fluxes are estimated applying different measurement techniques (in situ and remote sensing) and on different scales, using ground-based, airborne and spaceborne measurement platforms. Ground-based measurements include mobile in situ instrumentation with mass flux estimates based on a Gaussian plume model (Korbeń et al., 2022) and stationary remote sensing instruments (Knapp et al., 2023). Airborne measurements can be performed by UAV (Morales et al., 2022), helicopter (this study) and aircraft (Fiehn et al., 2020) equipped with in situ (Pühl et al., 2024) or passive remote sensing, e.g. AVIRIS-NG (Duren et al., 2019) or active remote sensing instruments, e.g. CHARM-F (Krautwurst, 2021). Observations from an increasing number of satellite-based instruments currently are used to derive CH4 emissions from space, with promising recent methodological advances which are expected to continue (see Jacob et al., 2022 for an overview).

Airborne in situ techniques measure directly at the position of the platform and therefore the plume of an emission source has to be crossed multiple times at different altitudes to gain a reliable mass flux estimate (Cambaliza et al., 2014; Hajny et al., 2023). By contrast, remote sensing instruments (airborne or spaceborne) can cover the whole plume by a single overpass, but typically need cloud-free conditions. In addition passive remote sensing observations are challenging to quantify within areas with complex albedo or water surfaces (Cusworth et al., 2019; Ayasse et al., 2022).

Measurement platforms often cover different scales, spatially and temporally, and (except satellite platforms) may carry in situ and/or remote sensing instrumentation. Hence, each combination of platform and measurement technique has its particular advantages and disadvantages. While ground-based measurements provide information close to sources with very low detection limits, satellites can measure on a global scale but are only able to detect sources with emission rates often larger 100 kg h−1, even with favourable conditions (Naus et al., 2023; Schuit et al., 2023; Thorpe et al., 2023; McLinden et al., 2024). Aircraft can cover large regional areas and altitudes ranges, and typically have a payload capacity which allows use of state-of-the-art instruments with low detection limits. However, aircraft deployments usually are limited in time, logistically complex and cost-intensive. In contrast, UAV deployments are much more cost-efficient and flexible, but have limited vertical extent (< 120 m in the drone category “open”), horizontal coverage (maintaining a visual line of sight between operator and drone), flight time (up to 90 min), and payload weight which hampers the use of high quality CH4 instruments (Burgués and Marco, 2020; Shaw et al., 2021).

Helicopter-borne measurements provide a reliable and complementary method in respect to the limitations of the other platforms to accurately quantify CH4 point source emissions. The unique helicopter-borne measurement system HELiPOD is equipped with a variety of greenhouse gas, aerosol, meteorological and radiation instruments, see Pätzold et al. (2023) for a detailed technical description. This platform is more flexible than most research aircraft and drones in many aspects:

-

Aeronautical certification is not needed for the HELiPOD, since it is operated as sling load, only attached mechanically to the helicopter by rope.

-

Engaging local helicopter companies with local knowledge reduces the risk of both delayed flight permissions and inefficient flight patterns.

-

The versatility of the helicopter allows for plume probing much closer to sources than is feasible by small aircraft. This is especially advantageous for separating and quantifying proximate sources in a complex emission landscape.

-

Lower altitudes can be probed with complete vertical coverage of plumes from 50 up to 3000 m, ensuring that the top of the planetary boundary layer (PBL) is reached in most cases (see Sect. 2.3).

-

More sophisticated CH4 instrumentation (payload up to 135 kg) can be operated on the HELiPOD compared to drones, and high-resolution wind measurements can also be carried out simultaneously.

-

The operation of both in situ and open-path CH4 instruments (based on two different measurement techniques) is advantageous as they can be operated simultaneously on the same platform, enhancing the reliability and robustness of the observations.

-

Helicopters are more flexible in adapting the trajectory at the scale of several kilometers than fixed-wing research aircraft, but with less line kilometers covered in the same flight time, making the helicopter-based approach more suitable for point source investigations.

The limitations of the HELiPOD are the payload (at the moment 135 kg) and the flight time which is limited to around 3.5 h when using a Eurocopter AS350, potentially limiting the measurement of large area sources, e.g. basin scale. During take-off and landing the measurements are further disturbed by the helicopter downwash and the operation of sling loads is limited over densely populated areas. Furthermore, compared to airborne measurements, visibility could be a limitation, as well as rain and strong winds. Hence, it is more sensitive to meteorological conditions compared to aircraft, but less sensitive compared to drones.

To test the HELiPOD as a tool for the quantification of CH4 emissions from industrial activities, isolated point sources are considered as suitable targets for our approach. Satellite imagery has identified the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (USCB) in Southern Poland as a hotspot for atmospheric CH4 emissions (Schneising et al., 2019; Schuit et al., 2023) where coal mine ventilation shafts are recognised as the major pathway through which CH4 is emitted to the atmosphere (Swolkień, 2020). They have already been investigated and characterised in previous measurement studies. Such measurements range from ground-based (e.g. Luther et al., 2019; Dreger and Kędzior, 2021; Menoud et al., 2021) to drone in situ (Andersen et al., 2021, 2023), aircraft in situ (Fiehn et al., 2020; Kostinek et al., 2021), aircraft remote sensing (Krautwurst et al., 2021) and satellite measurements (Tu et al., 2022). These studies often lack coverage of the measurements between ground-based instruments, conducted in or close to the coal mine facilities at a distance of up to 100 m (e.g. Swolkień et al., 2022), and aircraft-based in situ measurements, several kilometres downwind of the source (Fiehn et al., 2020; Kostinek et al., 2021), or satellite-based measurements, many kilometres away from the source (Tu et al., 2022). Our novel HELiPOD set-up can efficiently close this gap, with extensive high-quality measurements that are not possible with drone-based approaches. This enables separation of emissions from proximate sources, while covering the entire distance between near field (CH4 plume impacted by turbulence) and far field (CH4 plume impacted by wind speed/direction and atmospheric stability) as well as the entire vertical extension of the single plumes for applying a mass balance approach. As a result, more reliable CH4 mass flux estimates can be expected. While this gap can partly be covered with drones (Andersen et al., 2021) and small aircraft, these platforms have limitations related to data quality. Given high emission rates and favorable conditions (cloud-free, no water surfaces, etc.), remote sensing instruments like CHARM-F (Krautwurst et al., 2021) or MethaneAir (Chulakadabba et al., 2023) and a variety of hyperspectral satellites (with high spatial resolution) can have near and far field capabilities. By contrast, the HELiPOD is consistently capable.

Previous studies showed that in-mine CH4 safety and air flow sensors of coal mine ventilation shafts in the USCB can be used for CH4 mass flux estimates (Swolkień, 2020; Swolkień et al., 2022). Hence, we can compare our top-down estimates with these bottom-up estimates derived from time synchronised measurements (1 min time resolution) to negate the potential bias created through comparison with emission estimates derived from annual coal production data. Validation of the application of in-mine safety sensors to estimate CH4 emissions has shown that although specified uncertainties of the safety sensors are high, their measured CH4 concentrations are in close agreement with high precision instrumentation installed in the shafts (Necki et al., 2025). Overall, this makes the USCB with its isolated and well-studied CH4 point sources a perfect testbed for our novel helicopter-borne application.

Within the UNEP funded METHANE-To-Go-Poland (MTG-Poland) field campaigns, conducted in June and October 2022 in the USCB area, the HELiPOD system was deployed for the first time to estimate CH4 mass fluxes based on the mass balance approach. Four different coal mine ventilation shafts were evaluated, and each shaft was targeted with 2 to 5 flights. In summary, 19 flights were carried out, each with a duration of 2 to 3 h. An overview of the flights is given in Table S1 in Sect. S1 of the Supplement. The last two flights of the field campaign were dedicated to validating our applied methodology by quantifying CH4 emission rates from a simple controlled release experiment. Finally, our top-down CH4 mass flux concentrations are compared to bottom-up estimates based on CH4 safety sensor data from the owners of the coal mines. In this work, we describe the helicopter-borne application for measuring CH4 emissions close to point sources (Sect. 2) and present the results together with sensitivity studies for reliable CH4 mass flux calculations, which are further discussed (Sect. 3). We close with a summary and conclusions in Sect. 4.

In this section, we briefly describe the set-up of the MTG-Poland field experiment in the USCB (Sect. 2.1) and the helicopter-borne platform HELiPOD and its instrumentation (Sect. 2.2). In Sect. 2.3 we introduce the well-established mass balance approach for estimating CH4 mass fluxes and describe our sampling strategy (Sect. 2.4.) with associated uncertainties (Sect. 2.5), supportive ground-based measurements (Sect. 2.6) and CH4 safety sensor measurements in coal mine ventilation shafts (Sect. 2.7). In Sect. 2.8 we describe the set-up of a controlled CH4 release experiment.

2.1 Study region

The field experiment was set up in the USCB in Southern Poland and conducted in two separate measurement campaigns from 11–23 June 2022 and from 8–19 October 2022 to cover different weather conditions anticipated in summer and autumn (see Sect. S1). The campaign base was at the Bielsko-Biała airfield (EPBA, 49°48.30′ N, 19°0.12′ E) south of Katowice at a distance of 25 to 50 km from the measurement area.

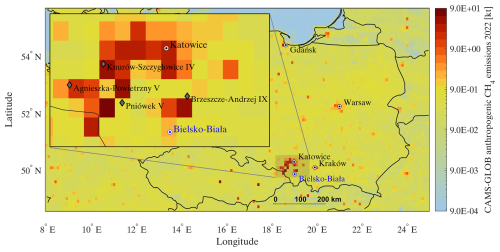

Figure 1Total anthropogenic CH4 emissions of Poland in 2022, based on CAMS-GLOB-ANT (Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service global anthropogenic emissions, 0.1° × 0.1°, version 6.2) (Granier et al., 2019; Soulie et al., 2024), where the shaded area around Katowice represents the USCB, enlarged with the locations of the four probed coal mine ventilation shafts in the left (grey diamonds). The blue dot indicates the campaign base at the Bielsko-Biała airfield. Emission data retrieved from ECCAD – the GEIA database (Emissions of atmospheric Compounds and Compilation of Ancillary Data within the Global Emissions InitiAtive) (re3data.org, 2023).

The USCB is known as a hotspot for CH4 emissions that result from coal mining activities (e.g. Schneising et al., 2019; Tu et al., 2022; Schuit et al., 2023). Figure 1 illustrates the importance of CH4 emissions in the USCB in the context of Poland for 2022. The targets of the helicopter mission flights were four pre-selected coal mine ventilation shafts with a preference to target metallurgical coal, high CH4 emissions strengths and mine owners willing to share data. Isolated locations further away from cities and other industries were preferentially selected with a road network that facilitated the mobile ground-based measurements, as described in Sect. 2.6. The probed shafts were Knurów-Szczygłowice IV, Brzeszcze-Andrzej IX, Pniówek V and Agnieszka-Powietrzny V (see Fig. 1).

2.2 The HELiPOD platform and its instrumentation

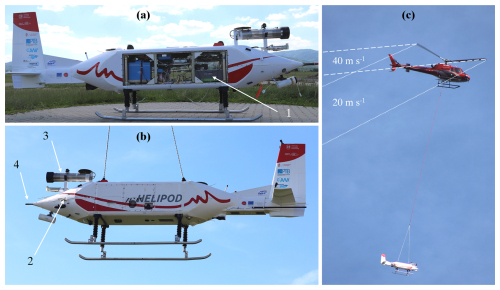

The HELiPOD (Fig. 2) is a helicopter-towed platform for atmospheric and other environmental measurements to investigate local and regional phenomena (Pätzold et al., 2023). It provides the possibility for flight patterns on a horizontal scale of typically 100 m to 100 km and at altitudes from 50 up to 3000 m. It has the dimensions of 5.2 m × 2.1 m × 1.2 m and a weight of around 325 kg, including payload. Depending on the scientific payload and the environmental conditions, the HELiPOD is powered by up to two integrated 5 kWh batteries, allowing for complete power independence from the helicopter. During MTG-Poland, the carrier of the HELiPOD was an Eurocopter AS350 Écureuil (Fig. 2, right) of the local helicopter company Helipoland (https://helipoland.com, last access: 3 June 2025).

Figure 2The helicopter-borne measurement system HELiPOD with instruments mounted inside and outside (a, b): Picarro G2401-m (1) with its inlet (2) for precise CH4 measurements, Licor LI-7700 (3) for high resolution CH4 measurements, and a five-hole probe (4) for precise wind measurements. Panel (c) illustrates the rotor downwash area for the air speed of 20 and 40 m s−1 (adapted from Pätzold et al., 2023).

To ensure turbulence-free atmospheric measurements of the HELiPOD, Pätzold et al. (2023) estimated the influence of the helicopter rotor wake. They compute a wake inclination angle of 6.5° for an assumed rotor thrust (equal to the helicopter plus payload weight of approx. 3.5 t and a rotor radius of 5.5 m) and a flight speed of 40 m s−1, which are the approximate measurement parameters. Therefore, the wake is just striking the top of the helicopter's fuselage but is far from the rope (length of 25 m) and the attached HELiPOD during cruise flight (Fig. 2, right). Only during take-off and landing, the HELiPOD is exposed to the rotor downwash for a short time. The typical flight duration is 2 to 3.5 h, resulting in a total flight distance of up to 500 km.

In addition to sensors for determining position and orientation at high resolution, the HELiPOD is equipped with around 50 sensors relevant to five fields of research: atmospheric dynamics, trace gases, aerosols, radiation, and surface properties (Pätzold et al., 2023). However, only the parts of the instrumentation relevant for this study are introduced here.

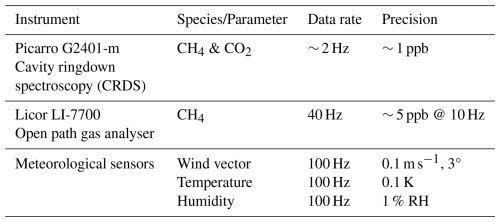

The scientific payload installed on the HELiPOD during the MTG-Poland campaign consisted of a variety of instruments to measure greenhouse gases and meteorological parameters, see Table 1. To minimize risks due to instrument malfunction and to evaluate the possible impact of the CH4 measurements on the mass flux uncertainty, we deployed two different in situ instruments for the measurement of CH4:

-

A Picarro G2401-m was mounted inside the HELiPOD centre section (Fig. 2, location 1), connected with a in. perfluoroalkoxy alkane (PFA) tube of 1 m length to the inlet at location 2.

-

A Licor LI-7700 was mounted outside on the HELiPOD front part (location 3).

The Picarro G2401-m, hereafter simply named as Picarro, is based on cavity ringdown spectroscopy (CRDS) (Crosson, 2008), while the Licor LI-7700, hereafter simply named as Licor, is an open path CH4 analyser (McDermitt et al., 2011), based on spectrometric measurement in near infrared (around 1.65 µm) inside the open optical cavity (Herriot cell) with effective laser beam path of 30 m. The flow rate through the Picarro is 300 standard mL min−1, leading to a latency of 5 s, which has to be considered in the data post-processing.

After each mission flight, maintenance work was performed, e.g. the mirror of the Licor was cleaned due to contamination from flies, black carbon and dust, which reduced the RSSI (Residual Signal Strength Indicator) during every flight typically by 30 %. On-site CH4 calibrations of both instruments were performed on average every second to third day using three different NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) corrected Air Liquide standards with high (2690 ppb), middle (1845 ppb) and low (1625 ppb) mixing ratios. We note, that the ppm and ppb notation is widely used in the trace gas community and, although not recommended within the International System of Units (SI), we apply it here for the sake of uniformity. Hereafter, ppm and ppb refer to the mole fractions µmol mol−1 and nmol mol−1, respectively. Laboratory calibrations with the three Air Liquide standards and two NOAA standards were performed before and after the campaigns and did not show any significant trends, deviations or outliers. Further information on the calibrations is provided in the Sect. S2.

A further important difference of the two instruments is the measurement frequency of 2 Hz (Picarro) and 40 Hz (Licor) and the respective precision of ∼ 1 and ∼ 5 ppb, respectively. The high sampling frequencies are advantageous to adequately sample the CH4 plumes. At the foreseen flight distances of ∼ 400 to 3000 m from the emitter, the plumes are typically expected to have a narrow width between ∼ 200 m to 1 km, which translates into ∼ 5 to 25 s sampling time within the plume at the typical HELiPOD flight speed of 40 m s−1.

During the flights, a subset of the measurement data is transferred from the HELiPOD via Wi-Fi to the operator's laptop in the helicopter, where it is visualised at the HELiPOD mission monitor. It combines a map of live data, where CH4 and wind measurements can be chosen, a time series of selected species and vertical profiles of various parameters. This data composition allows the scientific operators in the helicopter to monitor the performance of the system and to make decisions for the next flight manoeuvres (Pätzold et al., 2023).

The three-dimensional wind vector is calculated based on the vector difference between airspeed vector and groundspeed vector. The airspeed vector is determined by combining pressure data at a five-hole probe (Fig. 2, location 4) with position and the attitude angles of the measurement platform, which are determined using a Global Navigation Satellite System aided inertial measurement unit system (GNSS-IMU-System). The wind vector is provided at a frequency of 100 Hz. The accuracy of the wind vector is around 0.1 m s−1 for horizontal wind speed and 3° for the wind direction.

Temperature was measured with different fine wire sensors and resistance thermometers Pt100. Humidity was measured by a Lyman-Alpha instrument, different capacitive sensors, a dew point mirror and with an infrared absorption sensor Licor LI-7500RS, which also measures CO2. The signals from the different temperature and humidity sensors were complementary filtered to increase the accuracy and temporal resolution of the measurements (see Pätzold et al., 2023 for detailed explanations). All data of the individual HELiPOD sensors are collected and digitized with a client-master system, and stored with precise time stamp on the data acquisition systems. Calibrations of the CH4 sensors during the campaign and other post campaign calibrations were applied as part of the post processing. The airspeed vector measurement was calibrated in post-processing using wind calibration patterns.

2.3 The mass balance approach

We use the widely applied aircraft mass balance approach, described in detail in numerous publications (e.g. Cambaliza et al., 2014; Conley et al., 2017; Fiehn et al., 2020; France et al., 2021; Pühl et al., 2024), to estimate the CH4 mass flux of the coal mine ventilation shafts. The mass flux F of a species C through a crosswind curtain downwind of an emission source is estimated by the integration of the enhancement above the background concentration [C]bg combined with the wind speed component of the wind U⊥ perpendicular to the curtain, following Eq. (1) (e.g. Cambaliza et al., 2014):

The parameters z0 and zPBL top represent the vertical limits of the plume from ground to the top of the convective planetary boundary layer (PBL) and −x and +x represent the horizontal limits of the plume width from an arbitrary midpoint. The brackets around C denote the measured concentration. The full integration over the limits of the plane yields an emission rate F, in the unit kg s−1 or kg h−1.

We use a discrete approach of Eq. (1) by calculating the mass flux Fi for pointwise CH4 enhancements i (2 and 40 Hz) during individual transects crossing the plume at different altitudes downwind of the probed emission source, following:

where Fi is the discrete mass flux for a pointwise measurement [kg s−1], [ΔC]i = [CH4]i − [CH4]bg,i is the pointwise CH4 enhancement over the background mixing ratio [mol mol−1], M is the molar mass of CH4 [kg mol−1], pi is the air pressure [Pa], R is the universal gas constant [J mol−1 K−1], Ti is the temperature [K], is the perpendicular component of the wind speed to the curtain [m s−1], Wi is the horizontal extension of [ΔCi] in [m], equal to the distance between two pointwise measurements, and Hi is the vertical extent of [ΔCi ] in [m]. A detailed description of the mass flux calculation is provided in the Sect. S3. Here, just a brief summary is given.

The background concentration [CH4]bg,i is individually calculated for each transect and pointwise measurement i by interpolating between 10 s averages of both edges of a transect to account for gradients in the background. Methane plumes are identified by [ΔC]i+3σ, were σ is the mean of the standard deviations of the 10 s average periods at both edges. In that way, we account for uncertainties in the background concentrations and can separate plumes of targeted emission sources from other sources as well. The perpendicular component of the wind speed to the curtain is calculated from the measured wind speed Ui, wind direction and HELiPOD heading. The horizontal extension Wi of a pointwise CH4 enhancement is calculated based on the ground speed of the HELiPOD and the measurement frequency. The vertical extension Hi is estimated to reach halfway down to the next lower transect and halfway up to the next higher transect (e.g. Foulds et al., 2022; Pühl et al., 2024). If a mobile ground-based transect is available, the CH4 enhancements at the ground and the lowest transect are estimated to reach halfway down and up, respectively. In the absence of a mobile ground-based transect, CH4 enhancements of the lowest transect are estimated to reach to the ground. If CH4 enhancements at the highest probed transect are still present, they are estimated to reach to the top of the PBL. The PBL height is determined by deriving the temperature inversion height in parallel to a pronounced reduction in CH4 and water vapour. For this determination, we use measured vertical profiles of the potential temperature (θ) and its gradient dθdz−1, H2O and CH4 concentrations (e.g. Cambaliza et al., 2014), which were probed at the beginning and end of each individual flight up to an altitude of 3 km. Generally, we found the PBL not to be higher than 3000 m. Here we note, that all given altitudes are above ground layer (AGL).

Finally, the pointwise mass fluxes Fi are summed up to gain the mass flux of selected plumes on a transect (if emission sources are separated). These mass fluxes are then summed up to gain mass fluxes per transect which are summed up to obtain the total mass flux Ftop-down for the complete curtain. A detailed explanation in five calculation steps is provided in Sect. S3. The mass flux uncertainty is briefly addressed in Sect. 2.5 with more details being provided in Sect. S4. Mass fluxes are calculated separately for Picarro (2 Hz) and Licor (40 Hz) measurements. A comparison between both instruments revealed an excellent agreement (R2 = 0.99), with the Picarro measurements generally leading to lower mass flux uncertainties (median −8 %), see Sect. S5. Therefore, the final mass flux estimate per target and flight is the average of Picarro-based mass flux estimates for up to four curtains at different distances downwind of the emission source (see Sect. 2.4).

2.4 Sampling strategy

In general, gases emitted from point sources are mixed into the PBL during daytime or stay below a pronounced inversion layer (if present) within the PBL during night time or in the winter season. Depending on the wind conditions and atmospheric stability, the plume shape of these emissions differs (e.g. Geiger et al., 1995). For an unstably stratified atmosphere and low wind speeds with variable direction, the emissions will spread in all spatial directions which hampers a straightforward analysis of the airborne measurement data. For a stably stratified atmosphere with pronounced wind speed (> 3 m s−1), the emissions will be advected along the prevailing wind direction and theoretically form a cone shape broadening with distance from the source. The latter case can be approximately described by a Gaussian plume model (Sykes et al., 1986; Leelõssy et al., 2014; Conley et al., 2017; Hajny et al., 2023). Hence, our measurement flights were conducted during suitable meteorological conditions. The preferred wind speed range to probe the ventilation shafts was 3 to 10 m s−1 to allow for an effective spread of the CH4 plume. Depending on the wind direction and cloud forecast, the target ventilation shaft was chosen on a daily basis. The selected shaft was less impacted by other emission sources located upwind. Only days with a cloud base higher than 1 km were chosen to conform with the visual flight rules (VFR) for helicopter operations.

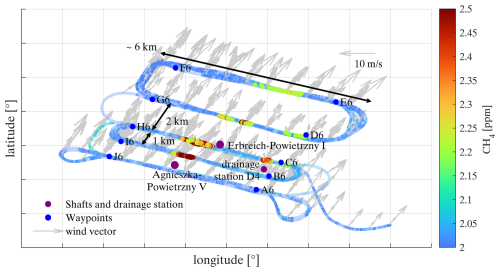

Figure 3Top view of Flight 07 on 17 October 2022, probing the shaft Agnieszka-Powietrzny V. Additional CH4 sources are the shaft Erbreich-Powietrzny I and the drainage station D4. All three sources are marked by purple points. Points A6 to J6 indicate the waypoints of the planned flight pattern. The wind direction was 195 to 225° (grey arrows) and nearly perpendicular to the performed mass balance experiments (MBEs).

A typical flight pattern is shown in Fig. 3, targeting emissions of the shaft Agnieszka-Powietrzny V. Straight race tracks with a length of around 4 to 6 km were flown perpendicular to the wind direction at different altitudes downwind of the target source to sufficiently capture the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the plume, as well as the background concentration at both edges of the plume transects (similar to e.g. Cambaliza et al., 2014; Heimburger et al., 2017; Fiehn et al., 2020).

Figure 4Cross view of Flight 07 on 17 October 2022. Three mass balance experiments (MBEs) downwind of the shafts Agnieszka-Powietrzny V, Erbreich-Powietrzny I and the drainage station D4 are selected for the calculation of CH4 mass fluxes. Points A6 to J6 indicate the waypoints of the planned flight pattern. The upwind leg and the last downwind MBE were excluded from the calculations.

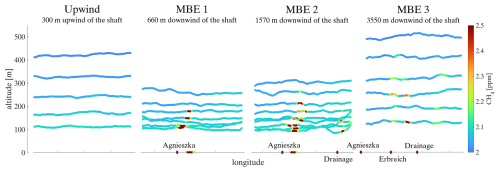

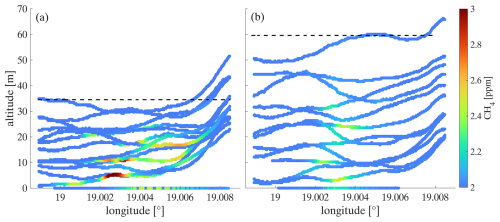

Figure 5Selected MBEs downwind of the shaft Agnieszka-Powietrzny V, probed at different distances during Flight 07 on 17 October 2022. Clearly visible is the dispersion of the CH4 plume with increasing distance from the source. In MBE 1 and MBE 2, ground-based transects are included at an altitude of 0 m, conducted between MBE 1 and MBE 2 (see Fig. S3). In MBE 2 and MBE 3, also additional plumes from a drainage station and the shaft Erbreich-Powietrzny I are visible. The upwind curtain shows that clean air masses are transported into the measurement area.

This creates a number of 2D curtains through which the mass flux is estimated (Figs. 4 and 5). The altitudes of the transects generally range from the lowest safe flight altitude (∼ 50 m) up to altitudes where no enhancements are detected any more (∼ 700 m). Depending on the plume height, between 5 and 24 plume transects were flown per curtain with vertical intervals between 25 and 75 m. Usually, a sequential probing was conducted starting from lower to higher altitudes and, if flight time remained, going back to lower altitudes again. This sequential probing ensures, that the whole plume is covered. Of these conducted transects, we selected 2 to 11 transects which are temporally close to each other (probed within ∼ 1 h) to consider approximately constant meteorological conditions (see Step 5 in Sect. S3). We conducted 1 to 4 downwind mass balance experiments (MBE) at distances of 500 to 5000 m from the emission source, starting with the curtain closest to the emitter (Hajny et al., 2023). In that way, we are able to separate nearby sources at closer distances were the plumes have not yet mixed, while having a better vertical and horizontal plume extent farther away, which also enables us to study the impact on the estimates.

In the example shown in Fig. 5, MBE 1 (waypoints I6 to B6) includes only emissions of the shaft Agnieszka-Powietrzny V. Here the importance of ground-based data is also visible. Due to flight restrictions the plume could not be probed below an altitude of 100 m, which means that 50 % of the plume information of MBE 1 is missing. Especially close to the emission source, where the plume is still narrow and not well mixed, the ground-based measurements ensure a reliable mass flux estimate. This will be further discussed in Sect. 3.3.3. Additional CH4 emissions from a drainage station and the shaft Erbreich-Powietrzny I (no explicit targets) were present starting with MBE 2 (waypoints H6 to C6) and MBE 3 (waypoints G6 to D6), respectively. The CH4 background concentration at the transect edges of MBE 1 is ∼ 60 ppb higher compared to MBE 3. The reason could be night time accumulation below a surface inversion layer close to the source or advected emissions from sources farther away. This behaviour was also observed during other flights with lower gradients. For the mass flux calculation, only MBE 1, 2 and 3 are selected, since at the fourth MBE emissions are already strongly mixed and are not distinguishable. However, the total emission rate of MBE 4 (1370 ± 396 kg h−1) is within the uncertainty range of the sum of the individual sources (1710 ± 514 kg h−1) . It is smaller because the plume has already spread out to the right edge of the MBE and hence the CH4 background concentration might be overestimated. The vertical dispersion of the emission plume from the shaft Agnieszka-Powietrzny V is clearly visible in the three MBEs probed at the distances of 660, 1570 and 3550 m downwind from the source (Fig. 5). Additionally, for every target we fly an upwind curtain at 3 to 5 different altitudes to identify possible upstream sources. In the example (Fig. 5), no upwind sources were detected. Only a small gradient of the CH4 background concentration with increasing altitude is present.

Generally, the choice of suitable probing distances highly depends on the strength of the emission source, the wind speed, atmospheric stability (Conley et al., 2017), as well as on the precision and temporal resolution of the instrument(s). Our race track distances (500 m to 5 km) are within the range of other aircraft-based mass balance approaches probing emissions of single point sources. Conley et al. (2017) probed at a distance of 1.5 km, Hajny et al. (2023) within 5 km, Pühl et al. (2024) at 2 to 7 km and Heimburger et al. (2017) and Fiehn et al. (2020) at a distance of ∼ 30 km from the emission source.

Flights were conducted mainly in the late morning until the early afternoon, when the PBL is well developed (Cambaliza et al., 2014; Heimburger et al., 2017) and wind speeds increase and disperse nocturnal accumulations. The duration of a mission flight varied between 2 to 3.5 h. The HELiPOD air speed is ∼ 40 m s−1 and thus considerably lower compared to other aircraft-based mass balance approaches, which are usually conducted at an airspeed of 60 to 70 m s−1 (Cambaliza et al., 2014; Conley et al., 2017; France et al., 2021; Hajny et al., 2023). In that way, the spatial resolution of the measurements is higher (0.4, 1 and 20 m for measurement frequencies of 100, 40 and 2 Hz), allowing for spatially closer probing and hence more reliable source separation in a complex emission environment.

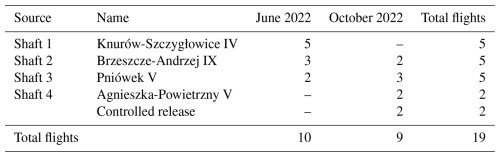

Table 2Number of HELiPOD mission flights to the different targets during the METHANE-To-Go-Poland field campaign in June and October 2022.

In summary, ten HELiPOD mission flights were conducted within the time period from 14–23 June 2022 and nine mission flights from 11–18 October 2022 probing four different coal mine ventilation shafts in the USCB region (see Table 2 and for more detailed information Sect. S1). The last two flights in October were dedicated to a controlled CH4 release experiment at the Bielsko-Biała airfield (see Sect. 2.8).

2.5 Estimating the mass flux uncertainty

The mass flux uncertainty Func (Eq. 3) consists of three parts: (i) Func_flux from the flux calculation (Eq. 2) via Gaussian error propagation, (ii) Func_bottom from the extrapolation of the lowest probed transect to the ground and (iii) Func_top from the extrapolation of the highest probed transect to the estimated top of the plume. We use this more conservative uncertainty estimate due to the closer probing to emission sources where the plume is not yet well mixed in the PBL.

The uncertainty Func_flux is obtained by summing up pointwise measurement uncertainties (Eq. 4) derived by Gaussian error propagation of Eq. (2) for identified plumes on selected transects, similar to the calculation of the total mass flux (see Sect. 2.3, also for the description of the parameters in Eq. 4). Detailed information on the errors σ of each parameter in Eq. (4) is provided in the Sect. S4.

The uncertainty of the plume height is considered separately. For the height of individual layers around the transect, no uncertainty is specified. Instead, we calculate mass flux uncertainties introduced by the altitude uncertainty of the top of the plume and the plume extrapolation to the ground (only if no ground-based data are available). Func_top is the mass flux uncertainty introduced by the estimated altitude of the top of the plume. We estimate the uncertainty of the top of the plume either to be half the distance from the highest transect with CH4 enhancements to the next higher transect without CH4 enhancement (if applicable). From this distance H, Func_top is calculated (see example in Sect. S4). Or, if the probed transect at the highest altitude still shows CH4 enhancements, the uncertainty of the top of the plume is estimated to be half the distance from this transect until the altitude of the next higher inversion layer or the PBL (see also Sect. 2.3). Func_bottom is the mass flux uncertainty introduced by extrapolating the plume from the lowest transect to the ground. If no ground-based data are available, the uncertainty of the lower plume limit is estimated to be half the distance from the lowest probed transect to the ground. From this distance H, Func_bottom is calculated. If ground-based data are available, Func_bottom=0.

2.6 Supportive ground-based measurements

The helicopter-borne MTG-Poland team was accompanied by further research teams carrying out ground-based measurements in the same area and at the same time, most notably mobile CH4 in situ measurements carried out by the University of Krakow (AGH) (Jagoda et al., 2024). The helicopter-borne team was partly guided by on-site reports of those teams by receiving the latest live observations via mobile phone.

In this study, the mobile ground-based measurements of AGH are used to complement the airborne CH4 measurements for the mass flux estimate at the lower altitudes up to 100 m, which are partly not covered by the HELiPOD. AGH performed mobile CH4 measurements by car equipped with a Licor 7810 and a Picarro G2201-i, with recording frequencies of 1 and 0.25 Hz, respectively, achieving precisions of < 1 ppb for the Licor and 5 ppb (30 s average) for the Picarro. The measurements were synchronized with GPS position data and wind data from a Gill WindSonic 60 anemometer at 1 Hz. Mobile ground-based data are added to the mass flux calculation, if they properly transect through the CH4 plume and if the measurements are close in time (< 1 h) and space (mean distance < 500 m) to the HELiPOD flight tracks.

Further measurements performed by the University of Heidelberg, Technische Universität of Munich, Technische Universität of Braunschweig and Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA), which are not part of this study, will be summarized in a synthesis paper.

2.7 Methane safety sensor data of coal mine ventilation shafts

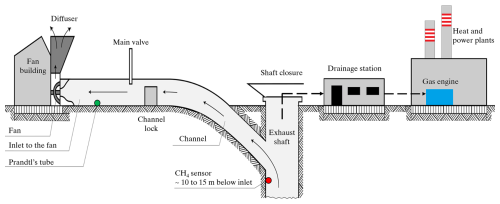

To ensure a safe underground work environment, hard coal mines have to implement control methods to maintain CH4 concentrations in the return air flowing from the excavation area below 1.5 % (Journal of Laws, 2017). Ventilation systems supply sufficient air to move and dilute more concentrated CH4 in-mine air that is generated from the gas emission zone. Sometimes an accompanying CH4 drainage system is used (see scheme in Fig. 6) to directly remove CH4 before it enters the ventilation system. The general principle of CH4 capturing consists of draining it from coal seams and surrounding rock through specially designed boreholes. Later, the gas is discharged via a separate system of pipelines towards the surface, utilizing the low pressure generated in a CH4 drainage station (Swolkień, 2015). For hard coal with a relatively low gas content, drainage is technically challenging and economically infeasible, hence, CH4 is emitted directly into the atmosphere by using only a ventilation system (Fig. 6). A drainage system is mostly used in mines with high CH4 emissions, where the air supply to the excavation is generally insufficient to reduce CH4 concentrations to a safe level. When not vented Polish coal mines use the drained CH4 either internally or sell it to external power plants. However, according to the Polish State Mining Authority (WUG), the average drainage efficiency of capturing CH4 is only 39 % in Poland, hence ventilation shafts release the remaining 61 % directly into the atmosphere (WUG, 2023). Of this 39 %, the average CH4 utilisation efficiency is about 68 %. As such, nearly a third of the CH4 captured by the drainage stations is released into the atmosphere (WUG, 2023). In Poland, drainage stations are therefore non-negligible CH4 emission sources, which account on average for 12.5 % of the total annual CH4 emissions of underground coal mines (Swolkień et al., 2022).

Figure 6Scheme of a coal mine ventilation shaft and optional drainage station. The position of the CH4 safety sensor is indicated by the red point inside the shaft, and the position of the Prandtl's tube is indicated by the green point inside the channel. Adapted from Swolkień (2020) and Andersen et al. (2023).

The CH4 concentrations in the ventilation shafts are monitored with an EMAG-Serwis-type DCH sensor (Detector CH4, EMAG Service: https://emagserwis.pl/produkty/metanomierze/, last access: 3 June 2025). This sensor (measurement range 0 % to 100 %, uncertainty 0.1 %) is part of the automatic coal mine gas measurement systems and is placed 10 to 15 m down into the exhaust shaft (Andersen et al., 2023), as shown in Fig. 6. The air flow rate in the ventilation channel is measured using a Prandtl tube (Fig. 6, green point) located between the main valve and the fan (Swolkień et al., 2022). The uncertainty of the Prandtl tube is 100 m3 min−1. For the calculation of the total air flow, also flow losses are considered, which are typically in the range of 2 % to 33 % of the measured air flow in the ventilation channel. These losses are calculated by the mine operators as the difference between the stream measured with the Prandtl tube in the channel and the stream measured at the bottom of the mine at the shaft inlet. The CH4 emission rate [kg h−1] is calculated following Eq. (5):

where [CH4] is the measured CH4 concentration [%], p is the pressure in the shaft [Pa], is the molar mass of CH4 [g mol−1] (16.043 g mol−1), R is the universal gas constant [J mol−1 K−1], Tshaft is the temperature in the shaft [K] and Vshaft is the air flow rate [m3 min−1]. The air temperature in the shafts ranges between 18 to 23 °C and the pressure between 967 to 983 hPa. The emission rates are calculated from the raw CH4 concentration and air flow rate measurements obtained every minute within each specific ventilation shaft for the time of the helicopter-borne measurements. The relative uncertainty of the emission estimates ranges from 14 % to 55 %. Industry data on the drained CH4 is proprietary and not publicly available (Swolkień et al., 2022).

2.8 Set-up of a controlled CH4 release experiment

Controlled release experiments are a typical tool to assess the mass flux quantification method and flight strategy (e.g. Morales et al., 2022). On 17 and 18 October 2022, two flights were dedicated to such a controlled CH4 release experiment, which was set up at the Bielsko-Biała airfield. CH4 was constantly released from an altitude of ∼ 7 m above the ground in the southwestern part of the airfield. The outlet was connected via a Bronkhorst mass flow controller to three 50 L gas bottles filled with 200 bar at the beginning (Air Liquide CH4 2.5 with a purity > 99.5 %). The release rate was ∼ 21 ± 0.5 kg h−1 CH4 during both experiments. The releases started at 12:37 UTC on 17 October 2022 and 09:37 UTC on 18 October 2022 with a duration of 57 and 41 min, respectively. Measurements were conducted with the helicopter flying at low altitude directly above the runway, perpendicular to the wind direction (∼ 200°) and 300 to 400 m downwind of the release point. This special set-up allowed probing at altitudes as low as ∼ 5 m above the runway ground. Additional mobile ground-based measurements were performed around and inside the fenced area of the airport. The primary objective of the experiment was to test the ability of the helicopter-borne approach to detect CH4 from sources with small emission rates. Detailed information on the controlled release experiment is provided in Sect. S6.

Here we show and discuss the comparison of the top-down mass flux estimates versus bottom-up estimates using in-mine data (Sect. 3.1), a sensitivity analysis of parameters which might influence the uncertainty and accuracy of our mass flux estimates (Sect. 3.3) and the results of the controlled released experiment (Sect. 3.4). As discussed in Sect. 2.3, all presented results are based on 2 Hz Picarro CH4 measurements.

3.1 Comparison with in-mine data

Bottom-up inventory estimates are often compared with top-down measurements as a validation approach aimed at improving the quality of bottom-up inventories. For the coal sector, inventory estimates are often annual averages using calculations that amalgamate contributions from different sources by using standardized emission factors upon reported coal production (Karacan et al., 2024). Given the uncertainties of comparing with annual inventory estimates, that are in any case unavailable at the mine level in Poland, and that are not specific to VAM or drainage station sources, we take a different approach. We use bottom-up estimates from in-mine data that is time synchronized to our HELiPOD measurements. The quality of data from in-mine CH4 safety sensor (Pellistor device) measurements has been recently evaluated through comparison to TDLAS (Tunable Diode Laser Absorption Spectroscopy) measurements set up by AGH (Necki et al., 2025), which were performed in the ventilation shafts. Results of this experiment revealed that bottom-up estimates based on the CH4 safety sensors and on the TDLAS measurements show a difference of less than 100 kg h−1, if proper calibration routines are applied. Within an uncertainty band of 14 % to 55 %, we consider the bottom-up measurements from in-mine data therefore as reliable and use them as comparator to evaluate the HELiPOD flux quantifications.

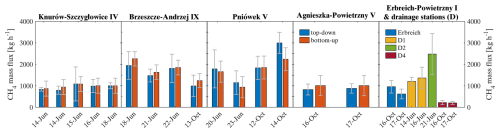

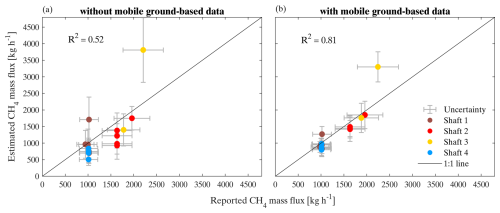

Figure 7Estimated top-down mean mass fluxes in comparison to in-mine bottom-up estimates for all MTG-Poland flights, sorted into the four targeted shafts. Additionally, emission rates of a fifth shaft (Erbreich-Powietrzny I) and three drainage stations D1, D2 and D4, close to Knurów-Szczygłowice IV, Brzeszcze-Andrzej IX and Agnieszka-Powietrzny V, respectively, are calculated.

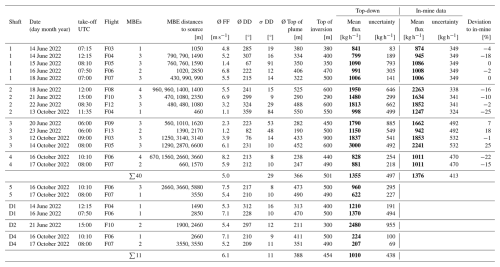

Table 3Summary of mass flux estimates from MTG-Poland and the comparison to bottom-up in-mine estimates. Mean fluxes and uncertainties are based on single MBE estimates for the respective HELiPOD flights. Mean fluxes of the bottom-up in-mine estimates are matched with the flight time period of each HELiPOD flight. FF is the wind speed, DD is the wind direction, Ø is the average for all plumes of the mass balance experiment and σ is the root-mean-square error. Shaft 1 (Knurów-Szczygłowice IV), Shaft 2 (Brzeszcze-Andrzej IX), Shaft 3 (Pniówek V) and Shaft 4 (Agnieszka-Powietrzny V) are the planned targets with available in-mine data. Shaft 5 (Erbreich-Powietrzny I) and the drainage stations D1, D2 and D4 (close to Shafts 1, 2 and 4, respectively) are additionally quantified and separately listed. The last rows list the average (except for the column MBEs, which is the sum) for 40 MBEs of Shafts 1 to 4 and for the 11 additional MBEs from Shaft 5 and drainage stations D1, D2 and D4. The average of the uncertainties is calculated using the geometric average. Estimates for every performed MBE with detailed information is provided in Tables S6 to S11 in Sect. S7. Bold values indicate the top-down and bottom-up mass flux estimates, respectively.

Out of our 59 curtains performed in total, 51 can be used for reliable MBE analyses. The remaining eight curtains showed a strong mixing of emissions from in- and outside the probing area (multiple shafts and drainage stations) and hence, were not included for further analysis. Figure 7 shows a comparison of estimated top-down mean mass fluxes and the bottom-up in-mine estimates for all shafts measured in June and October 2022, including uncertainties. Further details of the different top-down estimates are listed in Table 3.

The uncertainty for the top-down estimates ranges between 13 % and 73 % (median 31 %) and of the bottom-up estimates between 15 % and 55 % (median 32 %). For quantifying the bias of our MBE approach we calculate the mean error (ME) between the top-down and bottom-up estimates (Hajny et al., 2023), following Eq. (6):

where TDi is the top-down emission rate per flight, BUi is the corresponding bottom-up emission rate, and N is the number of flights. In addition, we performed a paired t-test to compare the means of the top-down and bottom-up estimates (Student, 1908; Hsu and Lachenbruch, 2014). The ME between top-down and bottom-up mass fluxes is −12 ± 32 kg h−1 and the paired t-test indicates that the means are equal (p-value = 0.86), hence there is no statistically significant bias. As mentioned above, we assume that the bottom-up in-mine data are reliable within their uncertainty range and we conclude that the helicopter-based approach is capable of reliably quantifying point source emission down to at least ∼ 200 kg h−1 (emission rate of drainage station D4). However, individual mass fluxes of single MBEs may differ e.g. due to changing stability conditions of the atmosphere, causing different dynamical behaviour of the plume, or simply due to the influence of other emission sources (Table S3 in Sect. S3 lists detailed calculations of three MBEs for a flight in October). The reason of the surprisingly good agreement might first be our sophisticated flight strategy with multiple MBEs in different distances of the source and multiple vertical transects covering in most cases the lower and upper edge of the plume. Second, the estimated emission rates of the ventilation shafts based on the bottom-up in-mine data are relatively consistent during the time period that HELiPOD measurements were performed. This indicates that emission rates did not vary significantly during individual flights, which infers constant excavation processes.

Due to the ability of our helicopter-borne method to separate nearby emission sources, we could estimate emission rates of four additional sources from 11 MBEs: one further ventilation shaft and three drainage stations. The fifth shaft Erbreich-Powietrzny I and two of the drainage stations were probed at two different days, showing similar emission rates within the uncertainty range (Table 3). Of note are the emission rates of the drainage stations D1 and D2, which have the same order of magnitude as the corresponding ventilation shafts, in fact D2 emissions exceed that of the corresponding ventilation shaft. Here we provide the first measurements that serve as independent estimates of CH4 emissions from drainage stations in Poland. This is of particular importance because emission rates of ventilation shafts and drainage stations are typically reported as a sum that represents the total for a given coal mine. Andersen et al. (2021) note that the WUG reports that the ratio of emissions from ventilation versus drainage sources is 4 : 1. While ventilation shaft emissions are continuous, although variability is not well known, those from drainage stations may be more intermittent and variable. When the corresponding emissions from three coal mines of the ventilation shafts (Knurów-Szczygłowice IV, Brzeszcze-Andrzej IX and Agnieszka-Powietrzny V) and drainage stations (D1, D2 and D4, respectively) are compared a 1 : 1 ratio is evident. The finding of broadly equivalent average emissions from the three ventilation shafts (∼ 1152 kg h−1) and corresponding drainage stations (∼ 1089 kg h−1) indicates that more attention needs to be given to the latter source. In the future, the measurement of drainage station emissions might become even more important, since they constitute an additional point source which, for the purposes of verification using top-down methods, should be reported separately.

3.2 Comparison to previous studies in the USCB

Previous studies mostly reported on measured emission rates without a detailed comparison to in-mine CH4 safety sensor data. For example, Luther et al., 2019 measured emission rates of 684 ± 114 to 1141 ± 114 kg h−1 for a single shaft using mobile sun-viewing Fourier transform spectrometry on 24 May 2018, which compare to emission rates of 1099 kg h−1 from the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR). Another study by Swolkień et al. (2022) reported average emission rates of 157 to 2018 kg h−1 with maximum values up to 3321 kg h−1 for 15 single shafts based on in-mine CH4 safety sensor measurements from 14 May to 13 June 2018.

Krautwurst et al. (2021) performed measurements by passive airborne remote sensing observations with the Methane Airborne MAPper (MAMAP) instrument in May/June 2018, mostly of shaft clusters consisting of four to seven shafts. For example, for three shafts of the Pniówek mine they observed 5900 to 8100 kg h−1, corresponding on average to around 2000 to 2700 kg h−1 per shaft. Andersen et al. (2021) report average emission rates during two days from 422 to 787 kg h−1 for Pniówek V in August 2017 and in another study 100 to 1700 kg h−1 in May/June 2018 (Andersen et al., 2023). In both studies they used AirCore samples collected with an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Also for May/June 2018, Swolkień et al. (2022) report emission rates from 0 to 2452 kg h−1 for Pniówek V. In general, all studies found large fluctuations in the CH4 emission rate for Pniówek from hour to hour and from day to day. Our estimated emission rates range from 1100 to 3000 kg h−1 for the shaft Pniówek V and fit well to these earlier studies.

In a more recent study, Knapp et al. (2023) performed remote sensing measurements of the Pniówek V shaft with a ground-based imaging spectrometer during the same period as this study. Compared to earlier studies they report larger emission rates ranging between 1390 ± 190 and 4440 ± 760 kg h−1 from 17 to 20 June 2022. For 19 June (08:45 UTC) they reported 2280 ± 160 kg h−1 which agrees well with the in-mine safety sensor data (2354 ± 492 kg h−1). However, during 20 June their reported emission rate of 4440 ± 760 kg h−1 is substantially higher compared to the emission rate derived from the HELiPOD measurements (1790 ± 885 kg h−1) and to the in-mine safety sensor data (1662 ± 492 kg h−1). Due to the wind conditions on that day (wind direction from 220° at 2.5 m s−1), we assume that they measured the cumulated CH4 plume of the shaft and the nearby drainage station, which we in sum estimated to be 4200 to 5500 kg h−1 (see Table S1, Flight F09).

Altogether, our estimates of CH4 emission rates for coal mine ventilation shafts in the USCB fit well to reported values of previous studies and comprise the first detailed comparison to in-mine safety sensor data for single shafts.

3.3 Sensitivity Studies

To better understand the parameters that influence the production of a reliable mass flux estimate of our helicopter-borne method, several sensitivity analyses were performed. In the next subsection, we analyse and address uncertainty and closeness to the in-mine data as related to wind speed and direction, the horizontal/vertical probing density and the impact of including mobile ground-based measurements.

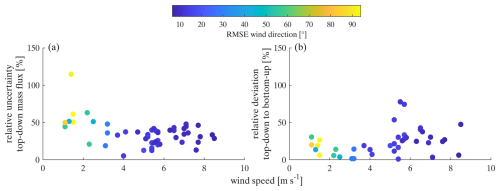

3.3.1 Impact of wind speed and direction

Figure 8a shows the relative mass flux uncertainty ( in percent) as defined by the wind conditions during the measurement of MBEs. Wind speed and the variation of the wind direction have a clear impact on the relative mass flux uncertainty. The mass flux uncertainty starts to increase when the wind speed decreases below 3.5 m s−1 and also when the wind direction variation increases to more than 30°, which naturally correlates with low wind speed. Figure 8b shows the relative deviation of the top-down to the bottom-up estimate in relation to the bottom-up estimate ( in percent) in dependency of the wind conditions. Surprisingly, at low wind speed the relative deviation between the two estimates stays below ∼ 30 %. Above 5 m s−1 the spread of the deviations is larger, potentially caused by probing a smaller plume cross section (due to the narrower plume shape at larger wind speed) and hence less measurement points within the plume. However, the deviations above 50 % belong to two distinct flights (Flight 8 in June and Flight 5 in October) and seem to have no clear influence from other meteorological parameters or with the flight strategy and are therefore considered to be outliers. Hence, Fig. 8b indicates that accurate MBEs might also be performed at low wind speed (< 2 m s−1), just with higher underlying uncertainties. During higher wind speeds and steady wind direction, it might be advantageous in future campaigns to probe plumes not perpendicular to the wind direction but with an angle of e.g. 30°. This enlarges the cross section through plumes, especially when flying close to the emission source, and hence the probing time which can lead to more accurate mass flux estimates.

Figure 8(a) Relative mass flux uncertainty and (b) relative deviation of top-down to bottom-up mass fluxes in dependency of the wind speed, colour-coded with the root-mean-square-error (RMSE) of the wind direction. This analysis includes 51 MBEs of our four targeted ventilation shafts for the relative uncertainty and 40 MBEs for the relative deviation to the in-mine data, based on Picarro measurements.

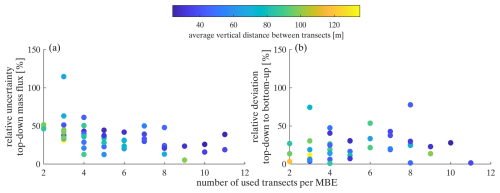

3.3.2 Density of probing

During MTG-Poland, the number of incorporated transects per MBE varied between 2 and 11 (see Sect. 2.4). The vertical distance between the transects ranged from 30 to 130 m (on average 72 m). Figure 9a shows the relative mass flux uncertainty in dependency of the number of incorporated transects per MBE. As expected this indicates a slight decrease of the uncertainty with increasing number of transects. However, with more than five transects the relative uncertainty stays below 50 %, i.e. 5 to 6 incorporated transects are sufficient (e.g. Tettenborn et al., 2025). Surprisingly, the relative deviation between the top-down and the bottom-up estimates seems to be less impacted by the number of transects (Fig. 9b).

Figure 9(a) Relative mass flux uncertainty and (b) relative deviation of top-down to bottom-up mass fluxes in dependency of the number of performed transects per MBE, colour-coded with the average vertical distance between transects. This analysis includes 51 MBEs of our four targeted ventilation shafts for the relative uncertainty and 40 MBEs for the relative deviation to the in-mine data, based on Picarro measurements.

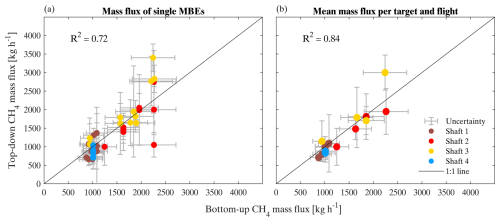

Figure 10Bottom-up estimates from in-mine data versus estimated top-down CH4 mass fluxes, (a) for 40 single MBEs of 2 Hz Picarro measurements and (b) for the mean per flight and target.

Furthermore, flying multiple MBEs downwind of the emission source increases the agreement between top-down and bottom-up mass flux estimates (Fig. 10). Mean mass fluxes of 2 to 4 performed MBEs per flight and target show a better agreement to in-mine data (Fig. 10b) compared to single MBEs which have a larger spread around the 1 : 1 line (Fig. 10a). Therefore, we recommend to conduct two or more MBEs at distances of 500 to 5000 m with the HELiPOD to gain a statistically robust mean mass flux estimate.

In further sensitivity studies, we also investigated the mass flux uncertainty and the deviation of top-down to bottom-up estimates depending on (i) the distance of the MBEs from the emission source, (ii) the altitude of the lowest transect, (iii) the altitude of the highest transect and (iv) the time of probing (see Sect. S5). For point (i) we conclude that there is no specific optimal distance, but a preferred distance range of ∼ 500 to 5000 m (according to wind speed and instrument precision) in which MBEs with the HELiPOD set-up should be conducted. The results indicate for point (ii) that a lower height of the highest transect is associated with a higher mass flux uncertainty. And for point (iii) that the mass flux uncertainty tends to slightly increase with increasing altitude of the lowest transect. By contrast, for the time of probing we found no large difference for either uncertainty or comparability of estimates.

3.3.3 In- and excluding mobile ground-based measurements

Mobile ground-based measurements complemented the helicopter-borne measurements and deliver important information for the lowest part of the plume. This is of particular importance when the lowest HELiPOD transect is higher than 100 m and/or the flight tracks are close to the emission source. Here, the plume is not yet well mixed and more than 50 % of the plume might not be covered by the flown transects. If a co-located mobile ground-based transect is available for a specific MBE, the enhancements at the ground are estimated to reach halfway up to the lowest HELiPOD transect, which is also estimated to reach halfway down to the ground. Without a mobile ground-based transect, enhancements of the lowest HELiPOD transect are simply estimated to reach to the ground, which may introduce an over- or underestimation. Therefore, single ground-based transects might have a large impact on the total mass flux estimate when flying close to the emission source.

Figure 11Reported bottom-up vs. estimated top-down mass fluxes (a) without mobile ground-based and (b) with mobile ground-based measurements. This analysis includes 15 MBEs based on airborne and mobile ground-based Licor 7810 measurements.

Figure 11 shows that mass flux estimates including mobile ground-based transects agree better with reported bottom-up mass fluxes based on the in-mine data. Mass fluxes in the absence of mobile ground-based transects show a mean deviation of 38 % to the in-mine data, whereas mass fluxes including mobile ground-based transects have only a mean deviation of 20 %.

Ground-based data was included when the car track fully transects through the entire CH4 ground plume, ensuring an enclosed peak, with CH4 background measurements on both edges. Furthermore, the ground-based measurements must be located close to the HELiPOD flight track in time (< 1 h) and space (mean distance < 500 m). Due to the irregular road system it was often difficult to synchronize the HELiPOD measurements to complete and co-located ground-based transects, leading to a successful integration of 15 out of 51 MBEs. For future HELiPOD field experiments where strong emission sources (> 500 kg h−1) in distances of < 1 km are probed, it is highly recommended to perform co-located mobile ground-based measurements below or close to the flight track whenever possible (as already proposed by Fiehn et al., 2020). Here we note, that for aircraft which usually fly farther away from emission sources and also at a higher altitude, this might not apply since the plume has already mixed in the PBL and the majority of the CH4 plume is located between > 100 m and the top of the PBL or an inversion layer.

We conclude that reliable mass flux estimates with moderate uncertainties (< 50 %) can be achieved by helicopter-borne measurements when probing at least 5 to 6 transects for more than two MBEs at distances of 500 to 5000 m and at wind speeds larger than 3 m s−1. Close to emission sources, including mobile ground-based measurements helps to improve the accuracy of the mass flux estimate.

3.4 Controlled release experiment

The primary objective of the controlled release was to test if the helicopter-borne approach is also able to detect CH4 from sources with a low emission rate. This was successfully achieved, as shown in Fig. 12 for Release 1 (17 October, 12:37–13:34 LT) and Release 2 (18 October, 09:37–10:18 LT) with CH4 enhancements of up to 1 ppm (2 Hz Picarro) above the atmospheric background concentration of ∼ 2 ppm. A detailed description and analyses are provided in the Sect. S6. Here a brief summary is given.

Figure 12Cross section of CH4 measurements from multiple helicopter and mobile ground-based transects (here altitude = 0 m) through the plume during (a) Release 1, 17 October 2022, 12:37–13:34 LT and (b) Release 2, 18 October 2022, 09:37–10:18 LT at the Bielsko-Biala airfield. The dashed lines indicate the estimated top of the plume.

The probing conditions were mostly comparable during both experiments with wind speed of 4 to 6 m s−1 and a wind direction of 200 to 225° (see Fig. S14 in Sect. S6). The total released amount of CH4 was 21.2 ± 0.5 kg h−1 (Release 1) and 21.3 ± 0.5 kg h−1 (Release 2). The cross sections in Fig. 12 show that, compared to the conducted MBEs for the ventilation shafts (Fig. 5), the flight altitude changes during the plume crossing and that multiple overlaying transects were conducted (Fig. 12). In this case, the approach introduced in Sect. 2.3 and 2.4 might not result in correct mass flux estimates, when applied in the same way. Therefore, we additionally applied a binning and a single-transect approach to estimate the mass flux during the release experiment, which are both described in detail in Sect. S6.

The estimated release rates of these three approaches range from 14 to 22 kg h−1 with uncertainties of 13 % to 70 % (see Table S5 in Sect. S6) and hence, are in the order of magnitude of the released amount of ∼ 21 kg h−1. Although the flight pattern during this simple release experiment deviated from those applied during the probing of the coal mine ventilation shafts (varying altitude during plume crossing, top of plume below 60 m), we conclude that besides detecting low CH4 enhancements, our helicopter-borne method is also capable of quantifying small emissions at rates of ∼ 20 kg h−1. As this simple release experiment was successful it provides validation of our method's ability to reliably quantify CH4 emissions from point sources with small emission rates.

A helicopter-based mass balance approach using the HELiPOD offers a robust and reliable as well as highly flexible method to quantify CH4 emissions from point sources. Engaging local helicopter companies facilitates flight operations, particularly in countries where access for foreign research aircraft is restricted. As an external sling load, it requires no aeronautical certification, allowing for uncomplicated modifications. The versatility of the helicopter enables plume probing as close as several hundred meters downwind, providing full vertical plume coverage from 50 m to 3 km altitude. This capability is particularly advantageous for probing, separating, and quantifying individual sources in complex emission landscapes. We showed that our helicopter-borne method can effectively quantify CH4 emissions from coal mine ventilation shafts and drainage stations. These results are based on an explicit flight strategy.

An optimal sampling strategy strongly depends on local conditions such as emission source strength, meteorological factors (e.g., wind, atmospheric stability), the temporal resolution of deployed instruments, the velocity of the measurement platform, and the surrounding environment (e.g., vegetation, topography, remoteness). However, based on our experience, several lessons learned can be drawn to retrieve reliable mass flux estimates of CH4 point sources using a helicopter-based approach:

-

Constant wind conditions with wind speed of 3 to 10 m s−1 and a consistent wind direction (RMSE < 30°) reduce mass flux uncertainty.

-

Ideally, full plume coverage from the bottom (as low as safe to fly, preferably below 100 m) to the plume top should be achieved, with vertical distances of 25 to 100 m between transects.

-

Assessment of the plume top altitude before and after every point source probing through vertical profile measurements.

-

Temporally tight probing of a MBE through the plume (less than 60 min per MBE for the MTG-Poland campaign) to ensure consistent meteorological conditions.

-

Sequential probing from the lowest to the highest altitudes or vice versa.

-

Including mobile ground-based measurements, especially close to the emission source, reduces the uncertainty.

-

Conducting ≥ 2 MBEs increases the statistical significance.

-

Conducting one upwind curtain allows to assess the overall CH4 background.

Additionally, a simple CH4 release experiment was conducted. Results show that the helicopter-borne method can detect and quantify small emission rates down to 20 kg h−1 from single point sources. This emphasises the wide range of potential applications in quantifying sources with both lower CH4 emissions, e.g. from biodigesters, landfills, cattle feedlots and manure pits, and higher emissions from industrial activities, making the HELiPOD an ideal tool to support reduction efforts of such emissions in the coal, O&G, agriculture and the waste sector.

Our confidence with the quality of the mass balance approach is reinforced by the close agreement with time synchronised quantifications derived from in-mine CH4 safety sensor and air flow data. Our estimated top-down mean mass fluxes align with bottom-up in-mine data, all within the uncertainty range and without statistically significant bias. The variability that both approaches capture shows not only that reconciliation between these vastly different approaches was successful, but it reinforces the limitation of comparing short term (1 h) campaign measurements with annual average emission inventory data. Our results support the application of the mass balance approach to define emission fluxes from industrial sources and the possibility of applying continuously derived in-mine data for greenhouse gas (GHG) reporting from coal mine ventilation shafts, emphasising the benefits of both approaches.

However, from the close agreement of both approaches one cannot conclude that more complex top-down measurements can generally be substituted by bottom-up data. This first depends on the emission landscape wherein the estimates are made and second on the quality of measurements. The coal mine ventilation shafts in Poland are strong and well-defined CH4 point sources with good conditions to reliably estimate mass fluxes, which is the reason why we chose them to test our helicopter-borne approach. Regarding the quality of measurements, we note that the accuracy and representativeness of derived in-mine data depends on the applied technology and location in the ventilation system and independent on-site measurements should evaluate their usability for GHG reports. In more complex environments like the oil and gas, waste and agriculture sectors, with their partly diffuse CH4 emissions, bottom-up methods can deliver first estimates but top-down approaches are mandatory to validate emission estimates (Nisbet and Weiss, 2010; Zavala-Araiza et al., 2015; Wren et al., 2023; Riddick et al., 2024).

Our results confirm previous research that quantified CH4 emissions from coal mine ventilation shafts in the USCB. Our study reports emission rates ranging from 1000 to 3000 kg h−1. The strong correlation between quantifications derived from in-mine data and our atmospheric mass balance estimates supports the application of the former for GHG reporting, as is already the case, to some extent, in some countries including the U.S. and Australia. Given the variability evident from individual ventilation shafts, reporting based on continuous data may be preferable to more limited sampling approaches. The ability to separate co-located emission sources allowed us to study an additional shaft and three drainage stations which were located close to the targeted shafts. We measured emissions of drainage stations for the first time independently and found that they can be of the same order of magnitude, as those from ventilation shafts. Hence drainage stations are not negligible CH4 emission sources in Poland and should be reported separately. But more measurements of drainage station emissions are necessary to verify these findings.

Presently, satellite measurements can only detect strong CH4 point sources (more than several 100 kg h−1) under favourable conditions. Airborne imaging remote sensing observations are also an option for CH4 studies, however, they are challenging to quantify within areas with complex albedo or water surfaces. Furthermore, getting flight permissions for imaging spectrometers is complicated in many countries outside of Europe, such as on the Arabian Peninsula, where our helicopter-borne mass balance approach has recently been deployed in a study on further anthropogenic sources from the oil, gas, and waste sectors. Therefore, our approach supports closing the gap between local ground-based measurements near the source and satellite measurements, allowing us to separate and quantify emissions from nearby sources and also to validate the other measurement techniques. The unique HELiPOD platform serves as an independent emission verification tool, which has the ability to assist coal, oil, and gas companies, as well as governments, in prioritizing their CH4 emission mitigation strategies, actions, and policies.

The airborne dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.18160/YK4Y-NHHW (Huntrieser et al., 2025). The ground-based dataset is available upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-18-7153-2025-supplement.

The paper was written and the figures were prepared by EF with contributions from HH. The experimental design and flight planning were performed by HH, AR, FP and EF. HELiPOD supervision and data processing were performed by FP, LB, AS, SB and AL. Mobile ground-based measurements were conducted and processed by PJ and JN. The bottom-up industrial data were obtained by JS. Picarro and Licor calibrations were performed by ML and DP. The controlled release experiment was conducted by ML. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the improvement of the manuscript.